The Amazon is the world’s largest rainforest and a critical line of defense against climate change. But it’s been steadily deforested since the 1970s, with nearly 20 percent of its land area wiped out. This year, pervasive forest fires destroyed vast expanses of rainforest, and Brazil’s growing agribusiness is poised to transform more into farmland. Amna Nawaz reports from Mato Grosso, Brazil.

Read the Full Transcript

Judy Woodruff:

The Amazon forests are burning at a record-breaking pace, sparking serious concerns around the world.

The source? They are mainly being set by ranchers and farmers clearing the land for cultivation.

With the support of the Pulitzer Center, Amna Nawaz and producer Mike Fritz recently trekked deep into Brazil to witness what is driving this deforestation.

It's part of our ongoing series, Brazil on the Brink.

Amna Nawaz:

It's an environmental treasure stretching across more than two million square miles, about 60 percent of which is here in Brazil. But the Amazon, the world's largest rain forest and a vital line of defense in the fight against climate change, is under assault.

Mike Coe:

This was entirely forest 30 or 40 years ago.

Amna Nawaz:

Mike Coe is a scientist at the Woods Hole Research Center in Mato Grosso, Brazil. He's been studying and visiting the Amazon for 20 years. These trees, he says, are crucial, not just for how much carbon dioxide they absorb, but also for the role they play in cooling the planet.

Mike Coe:

Tropical forests take up something like a quarter of all what humans put in atmosphere. They're basically like a giant air conditioner. They are incredibly efficient at taking sunlight and water and putting it back in the atmosphere. And that leads to cooling.

Amna Nawaz:

Since the 1970s, the Amazon has been steadily deforested. Nearly 20 percent has already been wiped out. And this year, the region has seen record-breaking forest fires. Nearly 60,000 fires have engulfed vast sections of the Brazilian Amazon. The effects, Coe says, are clear.

Mike Coe:

What we end up with is, out here, it's about 10 degrees warmer on average throughout the year than it is inside the forest. And that's…

Amna Nawaz:

Ten degrees warmer out here in the deforested areas than it is where the trees are?

Mike Coe:

Absolutely. Absolutely.

Amna Nawaz:

The driving force behind the decline of the Amazon in Brazil? The rise of the country's booming agribusiness sector. So, unlike most of Brazil's economy, agriculture has actually been growing. It's been growing steadily over the last few years, fueled mostly by soy and cotton and corn crops like these. But critics say that that growth in the agricultural industry has come at the expense of the Amazon. In fact, an estimated 80 percent of the deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon is due to agriculture, a result of decades of permissive land use policies that transform huge swathes of this region into cheap farm acreage.

Monica de Bolle:

The agricultural sector has always been a major player in Brazilian politics going back to before even the proclamation of the republic.

Amna Nawaz:

Monica de Bolle is a Latin American expert at the Peterson Institute of International Economics.

Monica de Bolle:

She says, since the 1960s, Brazil has grown into an agricultural giant, now the world's leading exports of beef, chicken and soybeans.

Monica de Bolle:

There's a lot of political influence there. There's also a lot of economic power, because the agribusiness sector is the one bright spot in the Brazilian economy right now.

Amna Nawaz:

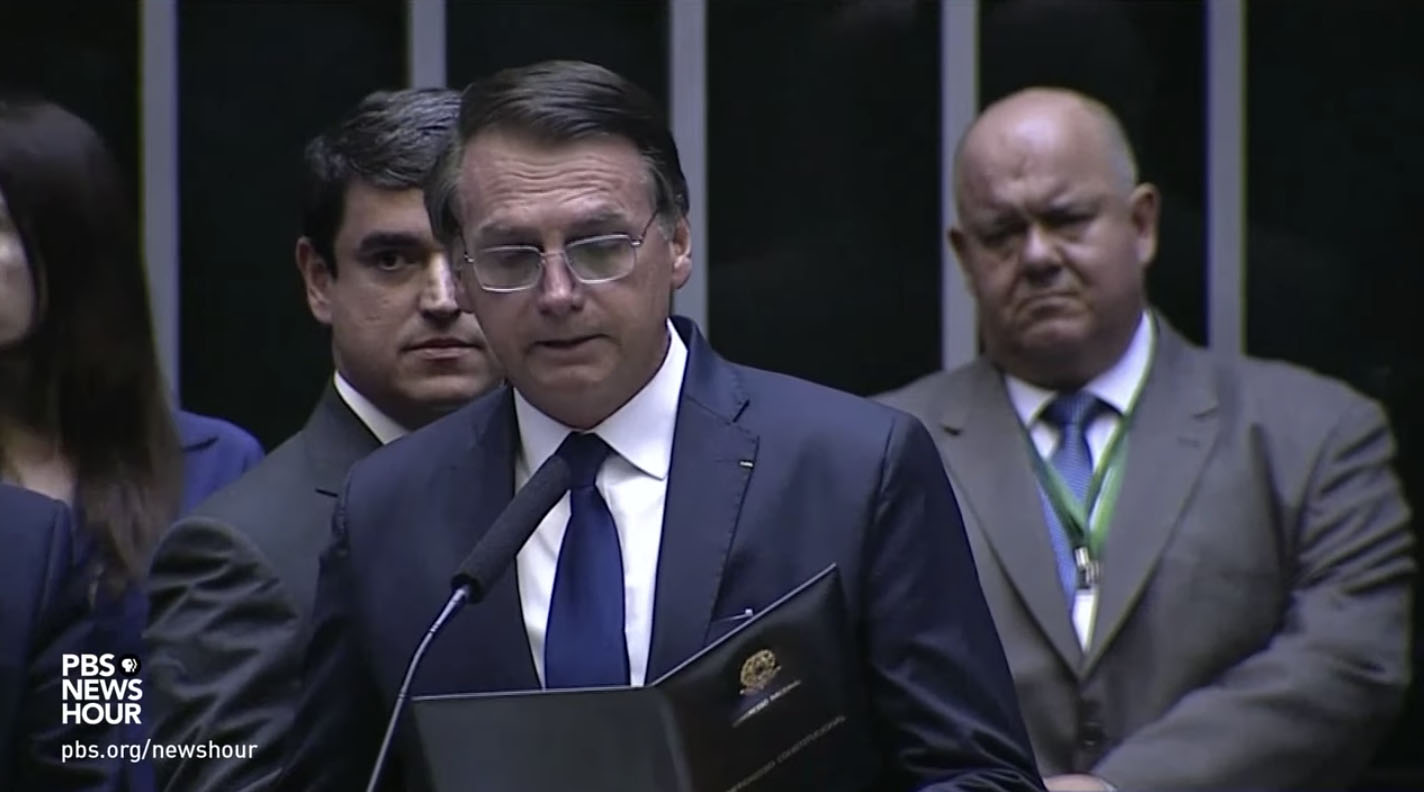

While GDP in Brazil has remained sluggish in recent years, growing by only 1 percent annually, agriculture has steadily risen by as much as 13 percent in 2017. And while deforestation in the Amazon slowed from 2004 to 2012, it's picked back up over the last few years, as new roads and infrastructure push development further into once remote areas. In January, a new threat to the Amazon came with the inauguration of President Jair Bolsonaro, a climate change denier. He has repeatedly pledged to open up more of the rain forest for business.

President Jair Bolsonaro (through translator):

Let's use the riches that God gave us for the well-being of our population.

Andre Guimaraes:

The government hasn't understood yet the risks of increasing deforestation for the reputation of Brazil for our markets and for our future.

Amna Nawaz:

Andre Guimaraes is the executive director of the Amazon Environment Research Institute. Further destruction of the Amazon, he says, is their chief concern.

Andre Guimaraes:

The entire world is trying to find the right way to promote our human activities in an environment within increasing temperature globally. And the Amazon plays a central role in storing carbon. So it's crucial maintenance maintaining the Amazon for the stabilization of the climate globally.

Amna Nawaz:

It's important to point out that not all deforestation is illegal. Under Brazilian law, farmers and ranchers can cut down up to 20 percent of trees like this on their own land if they need to. The problem, scientists say, is that the Bolsonaro government has rolled back inspections and monitoring and fines. They have basically made it harder to enforce the law. Since President Bolsonaro took office in January, roughly 1,000 square miles of forest has been lost, a nearly 40 percent increase from last year. Back in Mato Grosso, Coe and his colleagues are trying to understand the effects of all that destruction, measuring and monitoring, tracking trends in a shifting environment.

Mike Coe:

An average year today is like an extremely hot, dry year 30 years ago. So the climate has changed drastically because of deforestation and because of just the general climate change.

Amna Nawaz:

Coe says they are studying what happens when forest becomes farmland, in this case a soybean field.

Mike Coe:

What it's really doing is measuring how conductive the soil is. And the more water there is, the more conductive it is.

Amna Nawaz:

Why is that important?

Mike Coe:

Because, for the first time, we can get a picture of how much water there actually is. So, out in the soybean field, there's a lot more water in the soil. The rain comes in, it all goes into the soil. The trees use a great deal of it. The soybeans really don't, because, for nine months out of the year, they're really not doing anything.

Amna Nawaz:

Yes.

Mike Coe:

So it sits in the soil. And then it goes into the streams and just gets flushed out into the ocean.

Amna Nawaz:

As Coe explains, with fewer trees, less water actually goes back into the atmosphere after rainfall, which in turn leads to shorter rainy seasons and more frequent droughts. And the trees are responsible for pushing a lot of that water back up into the atmosphere, leading to more of the rain. You have got less rain here now, too, right? What does that mean?

Mike Coe:

The dry season is something like five months' long. So, already, by the end of dry season, they're running out of water. They're using what's left in the soil. And they're running out. And so you push another two weeks, that's a lot more stress on the forest. Same issue. The forest that remains is just under more stress. More of it dies.

Amna Nawaz:

This is just one of many multiyear projects being done by Coe and his team at Tanguro Ranch, a sprawling 200,000-acre industrial farm that sits at the very edge of the Southern Amazon. Soybeans, corn and cotton are all grown here, but it's also a research lab understand exactly the impact left behind. It's a rare partnership between agribusiness and the scientific community that dates back to 2004, when a few agricultural leaders in Brazil realized a balance between growth and conservation was needed. Divino Silverio is a scientist on that team. Often tasked with climbing high above the tree line, Silverio tracks exactly what's being lost from deforestation.

Divino Silverio (through translator):

So, I am here in this tower. And it allows us to measure how much carbon that this forest is assimilating or emitting into the atmosphere.

Amna Nawaz:

Born and raised in the area, Silverio is the son of subsistence farmers.

Divino Silverio (through translator):

It was natural for us to transform nature, to cut down the forest. That was normal for me. But what I learned in school helped me have a better understanding of the consequences. And it's important to emphasize that agriculture is important to everyone. We have to produce food. But, at the same time, it's also important to preserve nature as it is.

Amna Nawaz:

Safeguarding the forest doesn't have to come at the expense of agricultural development, according to Mercedes Bustamante, a biologist and professor at the University of Brasilia.

Mercedes Bustamante:

The economic activity that needs more environmental protection is agriculture itself, because we need water, we need good soils, we need pollinators. You need pest control. You need a very stable climate.

Amna Nawaz:

You're saying it could actually be better for that agribusiness if conservation were put first?

Mercedes Bustamante:

Yes. Yes. And, actually, if you see the land use in Brazil, we still have available land for the agricultural development and also for conservation.

Amna Nawaz:

The future of the Amazon now depends on finding this balance, says Thomas Lovejoy, an ecologist who has studied the rain forest since the 1960s.

Thomas Lovejoy:

We're seeing, I think, the first flickering of the tipping point, with historic droughts in 2005, 2010, and 2016.

Amna Nawaz:

If that tipping point is reached, which Lovejoy believes could happen if more than 20 to 25 percent of the Amazon is destroyed, it would be devastating to the region's ecosystem, creating hotter, drier weather patterns that will transform large sections of the jungle into a savanna.

Thomas Lovejoy:

He will go down in history as being the equivalent of the person who created the Dust Bowl in the United States.

The difference is between the Dust Bowl and situation is in the Amazon and in Brazil is, we actually scientifically understand what's going on and can avoid those tipping points.

Amna Nawaz:

And for scientists like Divino Silverio, avoiding that tipping point is not only crucial for the Amazon, but also for a place he has long called home.

Divino Silverio (through translator):

It's where I grew up, where my family lives. To me, this region is part of me. It's also special because of its extraordinary diversity, which has always been part of my life. So there's an intense feeling of loss when you see the changes that are happening.

Amna Nawaz:

For the "PBS NewsHour," I'm Amna Nawaz in Mato Grosso, Brazil.

Judy Woodruff:

And, tomorrow, our series Brazil on the Brink examines the threats faced by animals that call the Amazon home and potential solutions that will protect them.