For decades, monsoon floods have been eroding the riverbank of Triem Tay, an island village just a bridge crossing away from the ancient town of Hoi An. As his village shrank, Pham Duoc destroyed his old house to move further inland. Now at the age of 54, the former carpenter hopes the current and third house will be his last.

“I wasn’t sad,” Duoc said of the decision to abandon his second house of 30 years in 2018 after 2017’s historic flooding carried away 12 hectares of Triem Tay’s land. “That’s what I had to do.”

He was also worried that a green embankment he had helped build wouldn’t be stable enough to withstand future flooding. He wasn’t wrong. After eight consecutive floods triggered by fierce storms that hit central Vietnam in late 2020, two-thirds of the sonneratia mangrove forest they planted along the 650-metre-long west bank of the island disappeared. But the silver lining was that the land remained nearly intact.

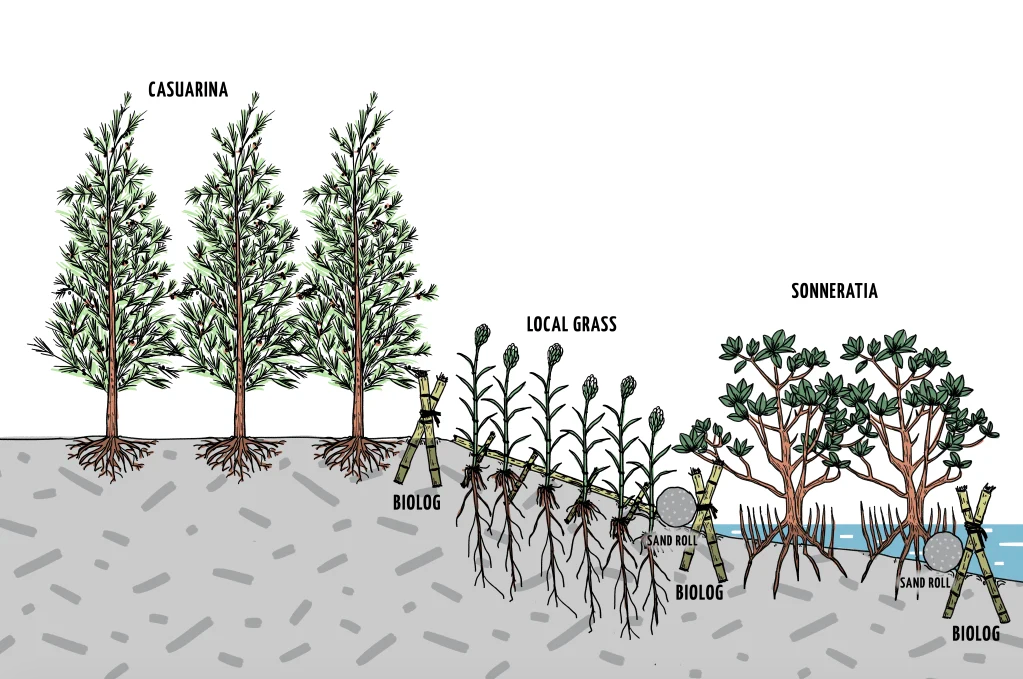

“Sonneratia are front-line plants and their death is like a sacrifice to protect the flora behind them,” landscape architect Dr Dao Ngo says. They form the first layer of what she calls a “soft” levee girding the riverbank. She doesn’t view the loss of the mangroves as a failure but an inevitable course of nature. “The green embankment is meant to embrace forces of nature rather than resist them and you’ve got to accept there are gains and losses to be made.”

Dao’s mangrove plantations, which she helped fund along with the city of Hoi An, are nothing like the concrete embankments commonly used throughout Vietnam and worldwide as shields against surging waters. Instead of confronting forces of nature, the green levees adapt, aiming to restore the natural riverbank ecosystem.

Triem Tay lies in the estuary of Thu Bon river, “a very sensitive and fragile area where ‘hard’ solutions [to erosion] won’t work”, said Dao, who has studied the region’s ecology for nearly two decades as an urban planning consultant. Here, dunes and islands rise and fall as water flows fluctuate between wet and dry seasons. Sixty years ago, Triem Tay was more than twice its current size.

The “common thinking among us humans is: we never want to lose land”, Dao says. “Between land and water, there always exists an ecosystem. If you put a barrier over it, it breaks down.”

As storms grow stronger and more unpredictable as the climate changes, the force that hits concrete embankments increases. In Dao’s words, “by fighting strength with strength, the destruction is going to be enormous”. The mangrove forest planted along Triem Tay’s riverbank is like a pillow that doesn’t stop but slows down the forces of nature.

Behind the first layer of deep-rooted sonneratia mangroves are fast-growing local grasses — a second layer that grows on a sloping bank designed to let the waves through while reducing their destructive force. They are then followed by the final layer of tall pine trees, which act as a natural windbreaker. The three layers are supported by a system of bamboo logs designed to help retain the soil when the trees are still young.

The villagers are also philosophical about floods. In Triem Tay, “people aren’t afraid of flooding”, says Nguyen Yen, a village elder. “We have learnt to live with the floods,” he said, seated in the parlour of his house, a traditional one-storey building with an attic for storage during the monsoon season. Outside in his garden stands a boat, which replaces bikes for transport during flooding.

Thirty years ago, Yen’s fellow villagers planted a bamboo forest by the island’s west bank to slow the waves and winds. Today, it is the unofficial fourth layer of the green embankment on a farm purchased by Dao as a way for an outsider to earn locals’ trust as she continues to test and refine her work.

But the future is bleak for the World Heritage-listed city of Hoi An, especially its beloved ancient port town where centuries-old yellow wooden shophouses line the Thu Bon river. No more than two metres above sea level, the city is flood-prone and vulnerable to rising sea levels, storm surges and coastal erosion. In 2016, a joint report by UNESCO, UNEP and the Union of Concerned Scientists warned that climate change would make conditions even worse from 2020.

Every monsoon season, local news outlets run pictures of the ancient town submerged in water. Millions of dollars have been spent on concrete embankments to save the city’s famous Cua Dai beach, to little effect. The causes aren’t simply climate change. Rapid development in the area, including the tourism boom that followed Hoi An’s recognition as a UNESCO world heritage site in 1999, has also caused problems. Dozens of hydropower dams upstream have changed the water flow and the amount of sediment brought downstream, while illegal sand mining, resort construction and a shift to intensive agriculture have all weakened the ground.

“Now the ecological component is extremely important. In the past it was culture, now it’s ecology,” Hoi An’s vice-chairman Nguyen The Hung said of the local government’s development strategy. The city has earned its place on the global tourism map, welcoming 4 million foreign visitors in 2019, compared with just 1 million in 2015, by betting on its cultural capital and ecotourism.

The shift to environmental projects, says Hung, is about encouraging a green mindset in everyday life and business. The city is piloting a weekend organic market, recycling restaurant waste and reducing reliance on single-use plastic.

“Of course, it is difficult and it will take time,” says Hung. “Perhaps we won’t succeed in this period but it will start changing with the young generation.”

As the city prepares to revise its long-term strategy in the pandemic’s wake, Hung doesn’t want to go back to being dependent on the tourists who once contributed 70 per cent of the city’s revenue. “We’ve got to try to preserve the maximum amount of agricultural land, like the rice fields that dot the urban landscape of Hoi An. As dozens of per cent of residents have farmland, there’ll be less to worry about.“

Ecology-based development, in Hung’s words, also means preserving the city’s forests, like the nypa palm mangroves in Cam Thanh commune at the mouth of the Thu Bon river. They currently make up the buffer zone of the Cu Lao Cham-Hoi An Biosphere Reserve but Hung wants this better protected. “If we achieve that, we’ll be able to keep the water coconut forest, preserve the ecosystem and locals’ life will definitely be improved.”

The mangrove forest is more than 200 years old but not native to Hoi An. Locals say their great-grandparents brought the trees from the Mekong Delta after noticing their ability to stabilise the soil. Over time, what started as a couple of trees planted outside houses by the river has grown into a vast forest that spans 120 hectares.

“You don’t see erosion here, but build-up [of land],” said Diep Van Nam, a 45-year-old construction worker and farmer who has been planting nypa palms for 10 years. During the 2020 historic storms, the nypa palms in Cam Thanh survived three days under water. “I’ve never seen these trees die because of flooding,” said Nam, adding that they could withstand a week-long deluge.

During the Vietnam-American War, North Vietnamese soldiers and locals hid in the nypa forest from enemy forces. Today, they are the first line of defence against storms for those living on the banks of the river. It is their root system, which Nam compares to intertwined tyres that go up to 1.5 meters deep into the ground, that keeps them standing tall and the muddy soil firmly in place.

The palms grow so fast that every year, to prevent the forest from blocking the river’s mouth, locals prune their trunks and leaves.

Before the arrival of bricks and concrete, houses in Cam Thanh were built of palm leaves. Now, they mainly serve as material to thatch roofs for cafes, restaurants and tourism accommodation.

Le Thi Huong’s family is one of the few who to this day live in a house built entirely from nypa leaves, nestled behind a row of the palms she planted more than 20 years ago to keep her safe from storms. To people living in poverty, the nypa palms are a literal lifeline, which is why 20 years ago Huong invested what she described as “a fortune” on seeds to plant a nypa forest behind her house on the banks of Thu Bon river.

Before the pandemic, she was among the hundreds of locals who made a living by taking tourists in a bamboo basket boat, which fits no more than three people, through the canals. But since early 2020, the 59-year-old woman, her sick husband and three children have all been out of work and rely on whatever nature has to offer, from fish and seafood caught in the sea to the nypa fruits, which can be made into a sweet soup.

“The livelihood of locals [of Cam Thanh] is strongly tied to the ecosystem of nypa palms; that’s why they protect it,” Hung explained.

Nypa palms were among the first trees Dao planted alongside the banks of Triem Tay in 2015. But their heavy trunks could not withstand the stronger currents around Triem Tay’s sandy soil.

In 2017, Dao started experimenting with sonneratia brought in from Quang Tri province further north. By the end of the year floods wiped out the seedlings, but the second and third layers of the soft embankment survived.

After this deluge, the city of Hoi An approved the extension of the green embankment in Triem Tay to cover the neighbouring Cam Kim commune. Local authorities have also advised several tourism projects to switch to soft embankments instead of their planned concrete ones. But authorities remain cautious about Hoi An’s toughest erosion sites, such as Cua Dai beach, preferring to invest millions of dollars in high-tech concrete embankments.

Meanwhile, the People’s Council of Quang Nam province, which governs Hoi An, recently approved the conversion of a hectare of mangroves in Cam Thanh into other purposes to serve a proposed VND518 billion ($A29 million) residential project, according to local media reports.

Six months after the 2020 floods, Dao is back at work with Duoc, workers and young volunteers to revive the green embankment. The remains of sonneratia are showing signs of recovery as additional trees are planted.

Local wisdom says heavy flooding comes every three to five years. Triem Tay villagers and the local real estate market are betting that the green embankment will survive.

This story was produced with support from the Rainforest Journalism Fund in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

To read a version of this article in Vietnamese, please visit Nguò Dôth.

- View this story on The Age