To see a map of deforestation's effects, click here.

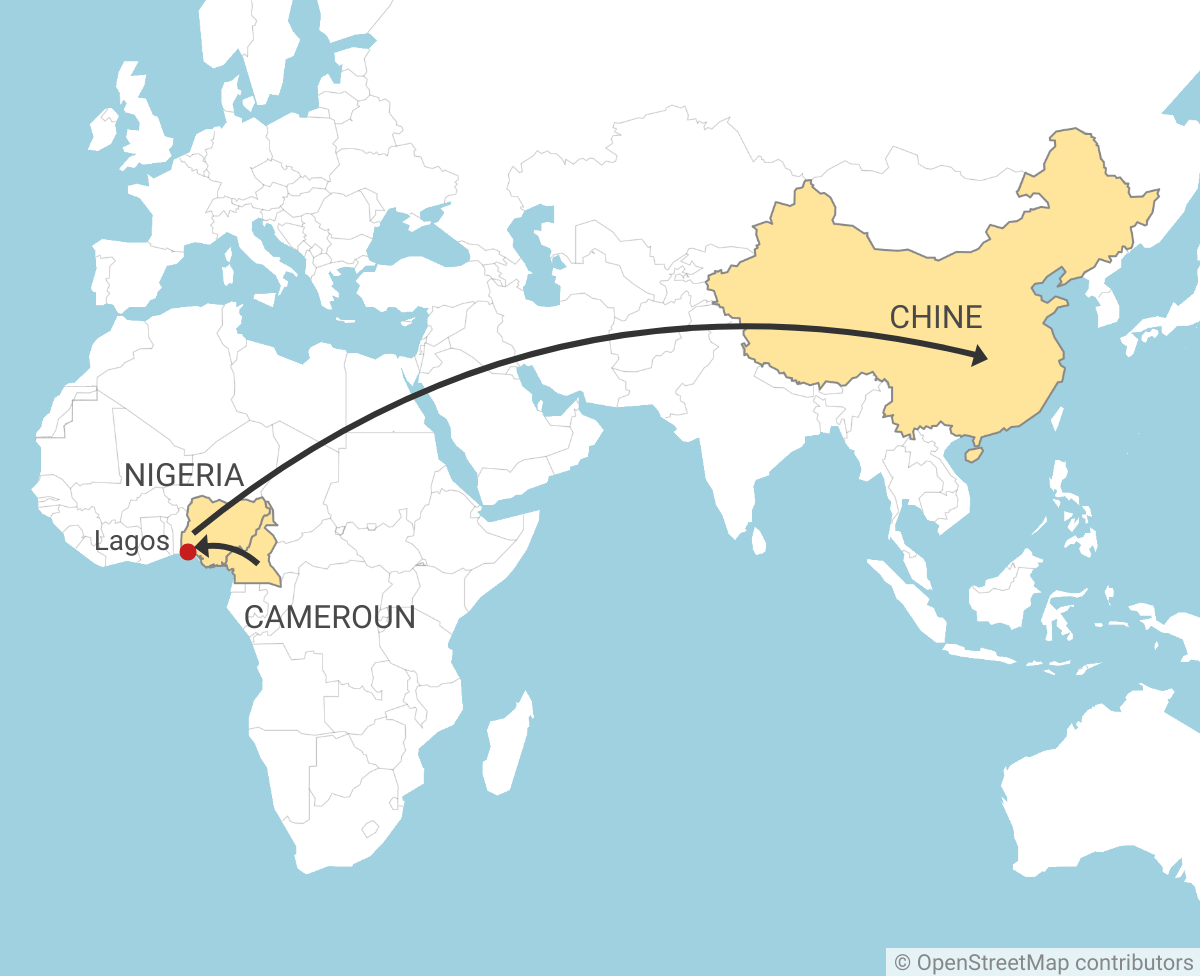

As rosewood is getting rarer in Nigerian forests, traffickers wanting to continue to satisfy demands from China have been harvesting this rare species of timber in neighboring Cameroon by bribing forest guards and, eventually, Nigerian authorities to change the origin of the fraudulent timber before exporting it.

Abdou Yadji wants to say goodbye to misery. The 40-year-old woodcutter ties his sweat-soaked t-shirt around his waist. With plastic shoes on his feet, he hacks at the trunk of the tree lying on the ground.

Abdou is under pressure. He has to cut out logs of wood of the same size before leaving the forest of Bamanga, a village in north Cameroon situated at the border with Nigeria.

The woodcutter is not alone in the forest. This hot morning of January 2020, his companion, a man with a satisfied look on his face, is sitting on a lump of ochre-colored earth, his eyes fixed on a silver watch on his left wrist.

Three days earlier, he had presented himself to Abdou as a Moslem businessman who usually buys Nigerian wrappers to stock his shop in the capital of the North region. Then with calm composure, he was admiring the work of the timber harvester and made a suggestion to him.

"He said he was in contact with a Nigerian businessman who wants to buy large quantities of Kosso wood and who pays 5,000 naira ($12) per a two-meters long piece,” Abdou said.

“If I sell the timber to him, he said, I could become rich within a short period.”

Cameroon and Nigeria share a 2,000 kilometers-long border and nationals of the two countries can discretely and without authorization enter Cameroonian forests and harvest logs of rosewood, which they transport to Nigeria, The Museba Project revealed in this investigation.

Whereas this lucrative activity is responsible for the destruction of the forests, the flight of public finances, and loss of employment, the online media outlet has discovered that certain Nigerian authorities linked to the main opposition party are involved.

They launder this type of rosewood, locally called Kosso or madrics, by delivering official documents to traffickers that attest that the logging was done in Nigeria, which facilitates the exportation of containers of Kosso to China, the final destination.

In addition, The Museba Project entered into contact with a popular trafficker of contraband rosewood who revealed the corruption network, which extends from the Cameroonian forest to the port of Lagos.

All it takes is a bribe given to Cameroonian forestry agents, traditional rulers, and Nigerian security agents. The price of rosewood logs in the black market the profile of Asian clients, and even how the trafficker and his team had successfully harvested Kosso from the dangerous forests of Borno state — territory which is partly controlled by the Boko Haram terrorist organization. This is a testament to how extensive the network is.

Abdou, 30, has been living in a straw-covered hurt without a wife nor children. Whenever he did earn a little money from cutting firewood, the woodcutter, who is also a chain-smoker, drank local beer, sang popular local songs, and hardly ate.

When the money ran out, he spent his time stretched out under the big tree of the village.

Bamanga is inhabited by about 5,000 people who live on farming, cattle rearing, and the sale of Bil-bil, a local beer. During the day and the night, motorbikes ply the streets of this small village. The drivers are transporting contraband goods coming from Adamawa State in Nigeria: cement, fuel, refined oil, flour, and sugar. Bike riders always create new routes to avoid the lone customs checkpoint in the locality.

The woodcutter welcomed the offer by the Moslem businessman as manna from heaven. He at least had an opportunity to get out of misery. But as he was treating a piece of Kosso wood under the burning sun, Abdou heard some noise from a distance.

His companion held his left hand and told him to run away. It was already too late. The two individuals were stopped on their short escape route by forestry and water agents working in the North region.

“You are under arrest,” said one of the officers in green uniform as he handcuffed the two accomplices. “You are not authorized to exploit this wood,” the officer said.

Organized looting

There is hardly a timber species as coveted as rosewood. Scientifically known under the name pterocarpus erinaceus, it is a rare tree which is found in the Sahelian zone and open forests. It is coveted for its fodder and therapeutic virtues. Its leaves serve as feed for domestic animals.

In certain regions of West Africa, the barks of Kosso are actively coveted for their traditional medicinal values. But if this wood has become one of the most adored species in the world, it is because it is abundantly used in the fabrication of luxury upholstery in China.

The Middle Kingdom, with more than 1.5 billion inhabits, has a new middle class which is ready to spend money on interior decoration.

In 2017, the luxury upholstery market in the country represented a business turnover of about $35 billion, according to experts. To realize this increase, China, a big exporter of upholstery, needs raw materials such as Kosso.

In 2016 alone, more than 1.4 million logs of Kosso valued at 300 million U.S. dollars were recorded in Chinese ports, reveals a study by the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), an NGO that researches criminality and environmental abuse.

All is not rosy in this hunt for rosewood. According to EIA, the strong Chinese demand has given birth to a parallel industry of illegal rosewood causing an organized looting of open forests throughout the world including those of certain countries to the south of the Sahara.

After Gambia, Ghana, Benin, Burkina Faso, and Sierra Leone, Nigeria, a country of more than 150 million, has seen its forests shrink as time goes on.

Between 1990 and 2010, Nigeria, which is the leading economic power in Africa, lost 409,650 of its nine million hectares of forest, which represents 2.38 percent yearly, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The sweep has not spared Kosso wood.

The new business in rosewood took its roots in the country in 2013. Profiting from the lapses in existing laws, a lackadaisical regulatory context, and the corruption of officials and community leaders, certain Nigerian economic operators and their Chinese counterparts have undertaken to finance the illegal harvesting, storage and exportation of Kosso.

EIA reveals that between January 2014 and June 2017, more than 40 20-foot shipping containers full of logs of rosewood were exported daily from Nigeria to China.

Nigeria, like Cameroon, is a signatory to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

Since 2017, pterocarpus erinaceus, or Kosso, has been listed in Annex II of this convention, which demands that exporting countries ensure that the origin of Kosso is legal and that its conservation is guaranteed.

In 2018, the CITES committee, preoccupied by the uncontrolled exportation of Kosso from Nigeria, decided that “the parties must not accept any permit or CITES certificate for pterocarpus erinaceus delivered by Nigeria except the CITES Secretariat confirms its authenticity.”

The repeated assaults by Kosso traffickers has already caused deforestation, global warming, and economic damage in states such as Cross River, Adamawa, Taraba, Kaduna and Ondo. When Nigerian traffickers discovered that forestry resources had run out while they must continue to satisfy Chinese demand, they started crossing the borders to illegally harvest Kosso in neighboring Cameroon.

Abdou did not have knowledge of this information when he accepted the proposition from the Moslem businessman.

“I want to make money in order to change my life and marry a woman, but I see that it is dangerous,” Abdou said.

Within some years, the forest of Bamanga has lost tens of logs of Kosso, according to local inhabitants. The wood is cut into pieces and transported clandestinely on motorcycles or trucks right to Nigeria. Traffickers propose attractive sums of money to poor woodcutters such as Abdou without explaining the risks involved in this illicit activity.

Sitting in the back of the white pickup truck of the forestry agents, Abdou neither thinks of the money he has to make after his efforts nor of his axe abandoned on dead leaves. The woodcutter was anxious to know what awaits him in the hands of local administrative authorities.

With 22 million hectares of forest, Cameroon is a forest giant in the Congo Basin. Rosewood is part of the rare species found in certain forests in the northern regions. Its exploitation is not industrial yet.

Cut into little pieces, a kosso tree of advanced age has always been used as firewood by populations in rural zones, but things have changed since some years ago. The authorities have since prohibited all exploitation of this wood. This is because hundreds of Kosso logs sawed or cut indiscriminately near the villages of the North region illegally leave the country.

“Trans-border traffic is generally rooted in well-organized criminal networks which link certain community leaders, wood traders, (local, regional and national) and foreign businessmen in charge of exportation,” said Raphael Edou, officer in charge of the Africa Reforestation Campaign Programme at EIA-US, adding that it “contributes towards the weakening of the state of law in Cameroon.”

Ousmanou Moussa, aged 80, is squatting inside a wooden hut. He is holding an iron bar which he delicately waves over a blue flame. In spite of his advanced age, the blacksmith still succeeds in making kitchen utensils and jewels liked by the inhabitants of Ouro Dalang village near the border with Nigeria. Ousmanou was the chief of Ouro Dalang for thirteen years before handing over to a successor in order to concentrate on his passion.

The man retains the memories of moments when he found it difficult to sleep because unknown individuals were entering the forest without his authorization to cut logs of Kosso and running away without leaving traces.

“We have for long sacrificed our sleep to remain awake and guard the village,” said Ousmanou with his legs crossed on a mat.

“These people came towards the end of the rainy season to cut the wood but we have made things difficult for them lately,” he added.

When Ousmanou talks of “lately” he makes allusion to September 2019. That day, his notables and himself caught a man sawing Kosso in the forest late in the night. The wood was confiscated while the trafficker and his material were handed over to the forces of law and order.

Traffickers use fire arms

The octogenarian regrets that this tree which provided shelter and the leaves of which served as feed for domestic animals is becoming rare in the village. He is not the only one who wants to understand what is happening.

“Some villagers thought these bandits were using magic to operate but me, I have never seen anything mystical in them,” Ousmanou said, adding that “someone cannot come to steal from you using magic.”

The Museba Project approached the forestry administration within the context of this investigation but they refused to make a statement. Nevertheless, an official involved in the fight against the Kosso contraband accepted to speak on condition of anonymity because he is not authorized to talk to the press.

According to him, there are no official figures on the looting of Kosso. However, he said, the administration knows the modus operandi of the traffickers.

“The traffickers come with fire arms, machetes, engine saws, and axes,” said the state agent, adding that “since engine saws make noise, and draw attention, they henceforth cut the trees with axes. That takes them three or four days to cut one tree but they prefer that in order to operate unnoticed.”

In Lougga Horre, another village in the North region, the inhabitants come out en masse when they hear the noise of engine saws in the forest, said Mamoudou. This sexagenarian villager with a padlock beard is at the head of a vigilante committee set up solely to track down cutters of Kosso. Three days weekly Mamoudou does not go to his millet farm. He sensitizes the villagers about the importance of protecting the environment.

“If we allow these people to cut down this wood, we risk being overcome by the desert, because there would be less rain and the soil would no longer conserve water,” Mamoudou declared.

Illegal forestry exploitation does not as yet constitute a serious threat in North Cameroon, according to experts. In 2010, the region had a forestry coverage estimated at 866,000 hectares spread through 13 percent of the land area, according to Global Forest Watch.

Ten years afterwards, it has lost 769 hectares, according to this platform specialized in the conservation of forests. The reduction in coverage is not always caused by deforestation, indicates Global Forest Watch, which notes that it could also come about due to fires or commercial exploitation.

Traffickers have not only been approaching woodcutters to get the wood. In certain cases, they offer money to traditional rulers who in return, grant them access to forests under their control.

After several weeks of negotiations, the reporter of The Museba Project succeeded in meeting a traditional ruler accused of corruption in his house. He accepted to tell his own side of the story on condition that he is not identified.

He said he had been approached, eight months ago, by a Nigerian trafficker with an attractive proposal.

“This man gave me a sum of 200,000 FCFA to allow him cut four Kosso trees in the forest,” said the chief. Later on, the agreement entered into secretly became public.

“I gave a little of this money to some of the notables, but one of them was ridiculous and thus started telling people that I took much money,” the chief declared, adding that he is very worried for having accepted the money.

“My image was tarnished and people no longer have confidence in me,” he said in a low voice.

Public condemnations by the populations have started bearing fruits. Thanks to them, the administration seized several stocks on Kosso wood and harvesting materials during field controls and traffickers have been brought to justice.

“Nigerian woodcutters have been arrested and they paid fines in order to put an end to the legal action and they were eventually released,” said a state agent, “but they can be pursued for illegal immigration”.

Wood seized during the course of an arrest, as that of Abdou and his companion, is parked at the Delegation of Forest in the North. It has to be sold by auction later on as stipulated by the law but the authorities are applying an exceptional measure.

“We burn the Kosso wood that we seize to avoid that by selling it at an auction it does not again fall into the hands of traffickers,” said a local agent of forestry and water.

Abdou and his accomplice spent eight weeks in judicial police cells in the North region. During their questioning, his accomplices revealed to investigators that his Nigerian contact is called Abdul Karim, a Moslem businessman who made his wealth in the traffic of rosewood. The two individuals risk up to three years imprisonment for unauthorized exploitation of forest but the administration has accepted a negotiated settlement.

“A woman close to the businessman presented herself to the police with a sum of 900,000 nairas ($2,200) to negotiate with the authorities and afterwards, we were released,” revealed Abdou Yadji.

After having been freed, Abdou returned to Bamanga, the village where he has been living since he completed secondary school in the neighboring Adamawa region.

Immediately after his arrival in the village, he joined the vigilante committee. He says he was shocked that he was involved in a criminal activity and has started reflecting on how to chase away the traffickers.

“What these individuals are doing to our village is not good,” said the woodcutter.

Abdul Karim

As the Kosso contraband activities were going on between the two countries, The Museba Project sought to know how the traffickers carry out their operations from the Cameroonian forest up to the exportation.

Almost all persons approached along the border have one name on their lips: Abdul Karim. We joined forces with Abdou to go in search of the famous trafficker who seems to know too much.

Mid-July 2021: Rains are scarce. Three small naked children walk on the dusty sand on the bed of the water that serves as the border between Bamanga and Jamtari, the closest Nigerian village. Nigerian immigration agents standing on the other side of the river approach our motor bike. The bike rider is used to such scenes. He murmurs certain words in Hausa to the policeman and gives him a 50 naira note. The barrier is lifted and the bike goes zigzagging between the houses, some of which are in mud bricks and others in cement blocks. Jerry cans of various sizes are abandoned here and there. After 10 kilometers, Konkul, a mid-rural and mid-urban locality, comes into view with its beautiful buildings and dry weather. Its untarred roads lead towards the market place which is full of businessmen that morning.

When Abdou came down from the bike, he heads towards a group of individuals with smiling faces. After some exchanges, one of them with a mobile phone withdraws from the crowd. He came back later and gives the phone to the woodcutter. Abdul Karim is on the other end of the line. The two men don’t know each other. Abdou introduced himself to the businessman as a woodcutter who has about eighty beeches of Kosso for sale near Kollere, another Cameroonian village situated near the border.

Without letting the woodcutter finish what he was saying, Abdul Karim reacted: “I want to buy all; don’t be worried about the transportation. I will take care of it.”

In Konkul, Abdul Karim is proprietor of a villa protected by a high fence. Only the roof is visible from outside. The man is however well known in the locality, being the most powerful businessman dealing in wood. After the short conversation with Abdou, Abdul Karim gave his personal telephone number to the woodcutter through his righthand man, a certain Inusa Zamfara Belel. He promises to come to Cameroon a week later for the transaction. Later on, Abdou called several times but the businessman could not be reached. The suspense has lasted nearly four months.

By the end of October, in the rain, this reporter, in search of the traffickers, went to Mubi, the second most important town of the state of Adamawa in Nigeria. Accompanied by a Nigerian journalist, he met Inusa Zamfara Belel. Dressed in a red polo, the righthand man said since about seven years, he has been working on wood trafficking. He said if Abdul Karim is famous, it was for at least three reasons: He is rich, he is the president of wood merchants in the locality of Maiha in Nigeria, and he bribes the authorities of Maiha in order to launder the wood coming from Cameroon.

“It’s our business” to bribe forest guards

“When he brings wood from Cameroon, he pays the local government in Maiha which makes documents showing that the wood is legal,” said Inusa Zamfara who sells beef and yams during his free time.

The young man declared that he uses engine saws to fell trees in north Cameroon where he pays about 9,000 nairas ($21) for a seven foot log but the same costs 15,000 nairas ($36) in Nigeria because, according to him, he has to spend the difference on bribery and taxes.

“If there is wood, we will buy, it is our business,” Inusa said. And when the Kosso is cut in Cameroon, it is transported by tricycles, light trucks, and our motor bikes right to the border, he added. The logs are eventually put into a ten-wheel truck which goes either to South Mubi or Maiha.

Inusa declared that afterwards, the convoys pass through Pella and Hong before taking the road to Lagos where Nigerian and Chinese economic operators buy the cargo destined for export. Inusa seems at ease. His boss, Abdul Karim was still unreachable. According to his righthand man, the trafficker is assisted by the Maiha local government.

Since the last regional elections, this local government has Idi Amin at the head. He is a member of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), a very strong opposition party which elected to the presidency of the country, people like Umaru Yar’Adua or Goodluck Jonathan. Idi Amin is supposed to be fighting against, among other things, contraband.

Talking by telephone to our reporter on December 10, he said he knew Abdul Karim and his activities. Had he aided him (Abdul Karim) in obtaining documents for the Kosso cut in Cameroon?

“Without problem,” replied Idi Amin who hurried to add: “I first want to call Abdul Karim, myself and himself would talk, then I will call you.”

Since this brief exchange, the Chairman of Maiha Local Government has not called again and has not picked up our calls. But the same day, a surprise awaited us. Abdul Karim who was not picking the telephone since the conversation with the woodcutter Abdou, called our reporter. The trafficker said he was still interested in the Kosso wood, even if he prefers another kind of wood, "appa wood," which creates fewer problems, according to him.

He has been carrying out the activity since five years ago, but he concentrated on the cultivation of maize for some time because, he says, the wood business is slow. He confirmed that he harvests most of his Kosso in Cameroon, where he bribes agents of forestry and water.

“In Cameroon, we negotiate with forest guards to harvest the wood and they afterwards authorize us to enter into the forest for a determined period for a convenient amount we pay them,” Abdul Karim declared, without revealing the amounts involved in the transactions.

“They (the forest guards) warn you that what they give to you is to enable you manage by yourself because it is not authorized,” Abdul Karim said. “They tell you that if you are caught, you are alone, don’t even mention them.”

Each year, the state of Cameroon loses about 33 billion FCFA ($57 million) because of corruption in the forestry sector. The civil servants suspected of being implicated in the traffic of Kosso are usually taken to court to dissuade personnel who want to adventure on the same path.

Last August, four forest guards and one customs official were brought before the North regional Appeal Court in a matter between them and the state. They were sentenced to three years imprisonment for corruption and complicity in illegal forestry exploitation of Kosso with Nigerian traffickers.

Haodam David, one of them, is finding life very difficult since being freed from prison and continues to claim his innocence.

“If we succeed in eating today, we say thank you to God; if there is no food, we take things as they are,” Haodam David said in an interview. “Until today, I don’t know why we were condemned,” he added.

It all started in June 2016. After corrupting the traditional ruler, four Nigerian traffickers who were harvesting Kosso were arrested by agents of forestry and water in Balkossa, a village in North region. Haodam was the forestry chief of section in the locality. He says that, eventually, the Nigerians wanted to negotiate their freedom by giving 689,000 nairas ($1,672) to the local forestry administration but Haodam’s hierarchy which expected to receive at least four million FCFA ($6,899) from this operation got the Nigerians arrested as well as the suspected civil servants, including Haodam.

Before this matter, Cameroon and Nigeria already had a bad reputation. The two countries had on several occasions been classified as most corrupt nations in the world by Transparency International. In spite of this all, this scourge is more present than ever before, and apparent in daily transactions.

The chairman and the dirty money

Abdul Karim is not only generous towards Cameroonian forestry agents. Once the harvesting of the wood is complete, the Kosso hits the Nigerian border.

The local authorities demand under-the-table handouts that can top 70,000 nairas ($140) per each truck load of Kosso for the delivery of documents attesting that the wood is of Nigerian origin, Abdul Karim revealed.

As Inusa indicated, Abdul Karim said he works with the Maiha Local Government.

“In Nigeria, there is freedom,” said the excited trafficker. “It is workers of the Local Government of Maiha who give us the papers certifying that we have paid taxes before we go to Lagos, because without your papers, you can sometimes be arrested and they would ask you to produce the approval which you have obtained for what you do. It is thus very dangerous to operate without the appropriate documentation.”

Idi Amin and Abdul Karim are linked to a point that they even exchange their telephones. The trafficker called our reporter with the telephone of the Chairman of the Maiha Local Government. That is not all: Abdul Karim is an intermediary. He works for a boss whose identity, and the name of the enterprise, he did not want to divulge, but his righthand man and other persons contacted suspect the Chairman of being the boss in the shadows.

“I will ask my boss for the name of the enterprise and then I will communicate it to you,” said Abdul Karim, who has since not picked up his phone.

The cargo of illegal Kosso which leaves the port of Lagos enters China, according to several traffickers. China, however, disposes of judicial instruments that permit to work against wood of doubtful origins.

In its Article 63, the recent forestry law authorizes the government to support the development of forestry insurance. Meanwhile, China is engaged together with the United States to eliminate the illegal deforestation in the world by applying the laws on the interdiction of illegal importation, but it hardly respects these engagements in spite of the implication of its citizens in illegal activities.

The Nigerian trafficker has revealed that to satisfy Chinese demands, his teams have exploited Kosso in Taraba, Adamawa, Kaduna and even in the state of Borno, territory which is in part controlled by the Boko Haram terrorist organization.

“Some of our agents work in the state of Borno, but they have been told to leave,” says Abdul Karim.

In Cameroon, the authorities have during recent years increased forestry surveillance in the north by providing financial and material means to vigilante committees. In addition, community forests have been created in the localities affected by contraband to push the populations to see them as a common good to protect.

“It is important to view the problem as a question of demand and offer instead of simply as a problem that Cameroonians and Nigerians are those responsible,” explained Raphael Edou.

“The authorities must suppress the networks facilitating passage and associated trafficking by using, for example, tele-detection which could assist in gathering intelligence, at the same time reducing the risk for the agents.”

While waiting, woodcutters such as Abdou remain vulnerable. Rich traffickers such as Abdul Karim, on their part, remain watchful.

This story was produced with support from the Rainforest Investigations Network (RIN) of the Pulitzer Center.