CALLERÍA, Peru — It’s a ritual that Roberto Zariquiey and Nelita Campos have engaged in for more than a decade.

The odd couple — Zariquiey, a university linguist conducting postdoctoral research at Harvard; Campos, the last lucid speaker of her Indigenous language — sit at the roughhewn kitchen table of her raised cabin, overlooking a muddy stream in the village of Callería, deep in the Peruvian Amazon.

“You complain a lot,” Zariquiey teases Campos.

“No, you’re the one that never stops complaining,” cracks back Campos, barefoot, with long jet-black hair that defies her 75 or so years.

Zariquiey, a 44-year-old professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, is slowly extracting the Iskonawa language from Campos.

He fires off questions, listens attentively to the answers and meticulously writes down all the details Campos can share: The vocabulary, grammar and syntax of one of the world’s most endangered languages. Throughout, the pair, who have built an unlikely mother-son relationship, joke incessantly.

Over time, Campos, who communicates with Zariquiey in both Iskonawa and Spanish, has managed to share much of this frequently onomatopoeic tongue from the Panoan family of languages of the Western Amazon. It’s heavy with polysemy — words with multiple meanings — and notable for allowing users to stack multiple verbs one atop the other.

Along the way, Zariquiey, who grew up in a middle-class family in Lima, has absorbed much of a culture finely attuned to its tropical rainforest environment, including the Iskonawa creation myth about an “isko,” a yellow and black bird that shoots its deadly feathers at humans who covet its stash of peanuts until a shaman persuades the angry fowl to share.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund coverage of Indigenous issues and communities. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Around the world, researchers are fighting a losing battle to save the world’s linguistic diversity. The most optimistic estimates suggest that half the estimated 5,000 languages spoken today, from Siberia to the Australian Outback, Africa to the Amazon, could vanish by the end of the century. The U.N. Department of Economic and Social Affairs warns that as many as 95 percent could be “extinct or seriously endangered” by 2100.

As these ways of speaking disappear, some linguists say, so, too, do ways of thinking. At risk are vital clues to unlock mysteries of human evolution, neurology, even medical science.

Campos’s story, and that of Iskonawa, is a complex one. At the tribe’s demographic peak, it might have numbered a few thousand. The population is thought to have plummeted during the 19th and 20th centuries as members retreated deeper into the rainforest to escape the rubber boom and the enslavers who drove it.

By 1959, when American missionaries convinced the Iskonawa to settle in a village where they could be evangelized, there were around 100 left.

For Campos, who was around 10 at the time, that seismic change marked the end of a childhood lived “naked” and “happy.” She was made to give up her Iskonawa name, Nawa Niká, and her native tongue. With her children and grandchildren, she speaks Spanish.

That was until six decades later, at the other end of her life, when this white stranger showed up. Instead of sneering at her language, Zariquiey told her it was beautiful and valuable. And more: He asked if she would work with him to preserve it.

“When he offered, and said he would write it down, I almost didn’t accept,” Campos says. “But now it gives me such happiness when I hear the recordings of my voice and see that the children want to learn.”

The tale of linguistic loss is common across the Amazon, in many ways the last front line in the clash of cultures that was ignited in 1492 by the arrival of Europeans in the Western Hemisphere. You can see ancient ways of life being crowded out by Western materialism in the forest villages, where satellite television and cellphones deliver English soccer, Hollywood superhero movies and Latin American telenovelas, and the booming jungle towns, where cheap colorful clothing and consumer electronics are sold to the blare of amplified tropical dance music.

[How four young children survived Amazon plane crash, 40 days alone in the jungle]

Zariquiey and Campos’s time-consuming work is both a labor of love and a race against the clock or, more specifically, against Campos’s mortality, an effort to document for posterity not just this rarest of languages, but also the unique, irreplaceable culture and knowledge it encodes.

“Each one of these languages is an expression of the creativity of the human mind, often with wisdom that we really have no idea about,” says Mandana Seyfeddinipur, who heads the Endangered Languages Archive at the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities.

Saving Iskonawa is particularly tough for Campos. Officially, she is 82, although it is thought that the date of birth recorded in government records — Dec. 30, 1940 — was plucked from thin air by the functionary who happened to be working in the remote jungle outpost of the Peruvian state where, as a young adult, her existence was formally registered for the first time. But whatever her true age, responding to Zariquiey’s precise and seemingly endless lines of inquiry requires commitment and focus.

The world was losing languages long before the pandemic. But it has been accelerated by the coronavirus and the carnage it has caused among tribal elders.

“It is globalization, urbanization and climate change,” Seyfeddinipur says. “People all over the world are under massive pressure for their livelihoods. This is the effect of things that we in the global North have created and are constantly still creating. We are losing this knowledge left and right, even as we run into museums to look at objects which are completely decontextualized, but where these people can tell you the story behind those objects.”

Few regions on Earth are as rich with languages as the Amazon, where an estimated 300 different tongues are still spoken, many of them “isolates,” meaning they have no known linguistic relative, in the way that, say, English and Dutch are connected, or Spanish and French.

Intriguingly, many of these Indigenous languages offer linguists, whose discipline bleeds into fields from anthropology and paleoarchaeology to neuroscience and philosophy, potentially far more promising lines of inquiry than the major Indo-European tongues.

That’s partly because the world’s most influential languages, starting with English, have already been the subject of the vast bulk of linguistic research. But it’s also because the most logical way for Western researchers to understand the outer limits of human language, culture or ways of seeing the world is to study the languages most alien to our own.

“What’s messed up is that most of the claims about human cognition, the psychology of Homo sapiens, are based on a very homogenous sample of human beings,” Zariquiey says. “There is this very big bias toward languages with similar characteristics, because all European languages, except Basque, come from the same common ancestor, and have generated similar patterns, which we think of as being universal but which aren’t, or at least haven’t really been proven to be so.”

That view challenges the prevailing thinking in modern linguistics, promoted most notably by MIT professor emeritus Noam Chomsky, whose universal grammar theory posits that our hardware — the human brain — strictly limits the parameters of any possible language. Others hold that the software — the language itself — is far more malleable and responds to the environment.

Underlying that abstract debate are some fundamental questions about human nature. How do we acquire and process language? Does the language you speak determine how you think? And do we really know all that the human brain is capable of?

Field linguists, such as Zariquiey, argue that we have barely scratched the surface of these profound puzzles. One example that appears to support that view is some Australian Aborigines’s instinctive knowledge of the cardinal points without need of a compass.

Even in windowless rooms, they know north from south — a capacity most Westerners have no inkling they could activate. Seyfeddinipur cites an Aboriginal elder signaling the capsizing of a boat. His hand movements would change from clockwise to counterclockwise depending on which direction he was facing.

Another key element of Indigenous tradition with potentially universal benefits is native peoples’ medicinal knowledge. Indigenous shaman are increasingly being recognized by modern biomedicine for their knowledge, gleaned empirically over thousands of generations, of the active compounds of the flora and fauna around them and how they can be used to treat illness and injury.

Big Pharma doesn’t publicize it, but a surprising number of important medicines originates in natural compounds. These include statins, which lower cholesterol, derived from fungi, and ACE inhibitors, used to treat high blood pressure, developed from the venom of a South American viper.

No ecosystem is more biodiverse — and therefore has more medicinal potential — than the Amazon, says Mark Plotkin, the ethnobotanist who heads the U.S. nonprofit Amazon Conservation Team.

He cites a single Amazonian species, the giant leaf frog, used in hunting rituals by tribes in Peru. Its proteins show promise in potentially increasing the permeability of the blood-brain barrier to allow medication to be delivered directly to the brain — a holy grail of modern medicine.

The irony is that just as Western science grows more adept at isolating natural compounds and evaluating their clinical properties, Indigenous languages and cultures in the Amazon are being ravaged more rapidly than the rainforest itself.

“We don’t even know what we’re losing,” Plotkin says. He noted the recent discoveries in the Amazon of two new species of electric eel and, in 2019, a tree nearly 100 feet taller than the one previously thought to be the region’s highest.

“These electric eels are eight-feet long slabs of meat. How do you miss those?” he asks. “You can’t pick apart a culture and say, ‘Okay, we want to save knowledge of the medicinal plants but we don’t care about the rest.’”

For Campos, the challenge is more immediate. She’s encouraging the children in her village to learn at least a little Iskonawa. Fortunately for her, she can count on support from Zariquiey, whom her sons now call “wetsako” — Iskonawa for brother.

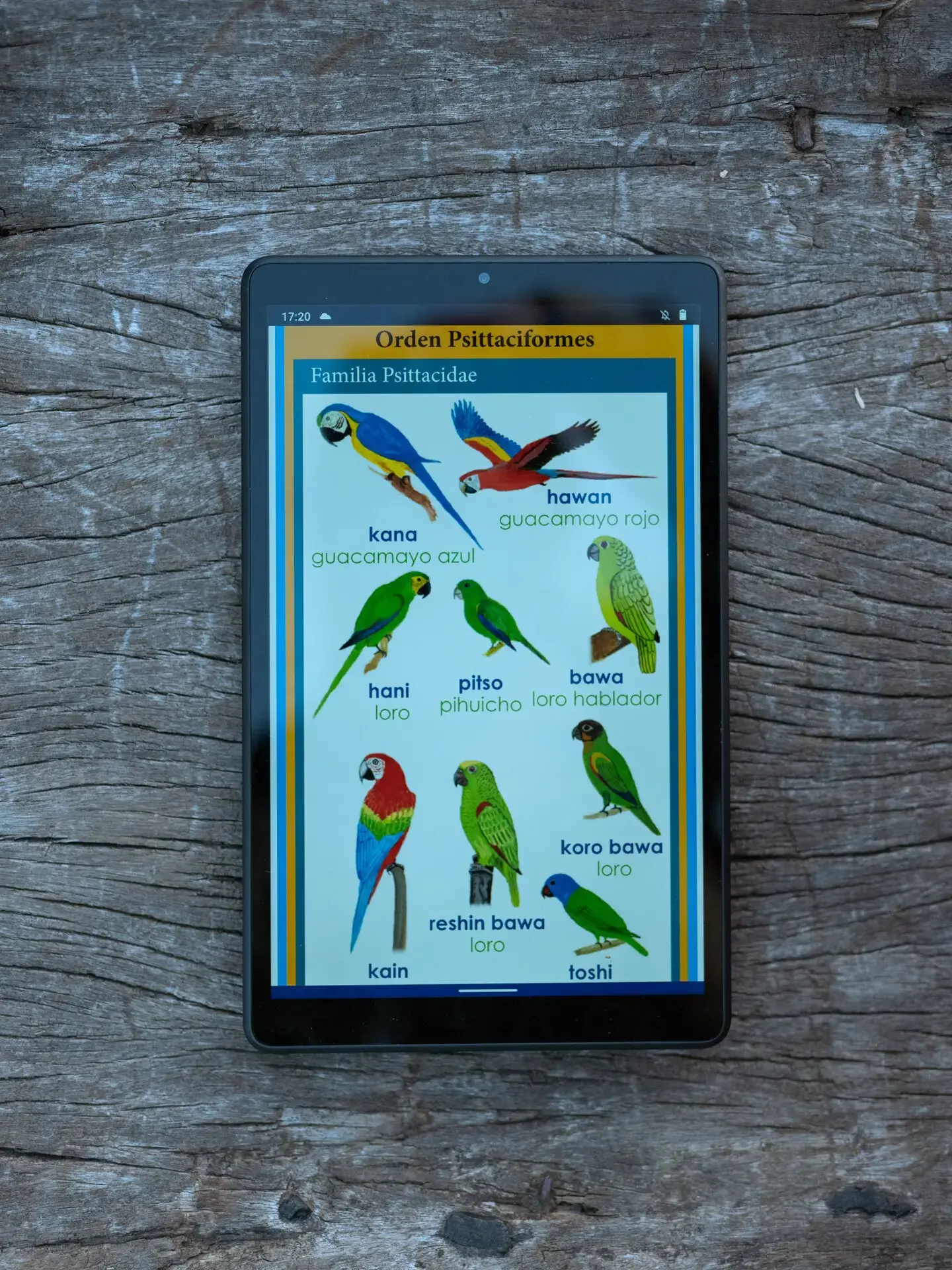

Zariquiey has created several Iskonawa vocabulary apps using Campos’s voice. They’ve become hugely popular in Callería. He has also launched a language school, where during his monthly visits, he teaches spellbound youngsters basic phrases from their ancestral tongue.

“Everyone thinks this language is obsolete, primitive or irrelevant, but when you see it on your cellphone, it changes that perception,” Zariquiey says.

Yet despite his and Campos’s efforts, he acknowledges that his students will never be native Iskonawa speakers.

Through the dictionary, grammar book and recordings the pair have been working on, Iskonawa will now survive indefinitely. But not as the kind of living, evolving entity that is used by a human community as a mother tongue. In that sense, much of the knowledge and learning encoded in it will recede into the past once Campos is gone.