To read the original report, written in Spanish, click here. This report is also availabe in Spanish on ArmandoInfo.

In February 2021, the Venezuelan military attacked a FARC dissident camp and a woman of the Jiwi ethnic group was among the dead. It was one of the first public indications of a reality that today affects different Aboriginal communities: Colombian guerrillas use different forms of bait to attract young people to join their ranks.

Whistleblowers and others in possession of sensitive information of public concern can now securely and confidentially share tips, documents, and data with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network (RIN), its editors, and journalists.

The death of a young woman of the Jiwi ethnic group in an attack by the Venezuelan Armed Forces against a camp of the so-called FARC dissidents in the state of Amazonas a year ago, in February 2021, offered a clear indication of two facts: not only that the Colombian armed groups had moved to southern Venezuela, but also that they counted among their ranks Indigenous people recruited on the spot.

The operation, called precisely Jiwi by the Venezuelan military command, was part of an unprecedented offensive by Caracas against the Colombian guerrillas. Just a month later, in March 2021, there was another attack by combined air and ground forces against positions of the Tenth Front of the FARC dissidents — commanded by Miguel Botache, alias Gentil Duarte — near the town of La Victoria, on the northern bank of the Arauca River bordering Colombia, in the State of Apure.

The escalation brought to light a new element in the tense situation on Venezuela's southern border, particularly in the regions of Los Llanos and Guayana, where for a long time Chavismo has shown itself indifferent — or willing to coexist — with the increasingly evident presence of Colombian armed groups.

In any case, the military campaign coincided with reports that internal disputes between the different guerrilla factions over control of illicit businesses and territories had escalated into fighting. And the intervention of the Venezuelan armed forces has been opaque at best. At least three prominent FARC dissident leaders — Jesús Santrich, El Paisa and Romaña — were assassinated in less than a year in Venezuela without Caracas releasing an official version of these episodes.

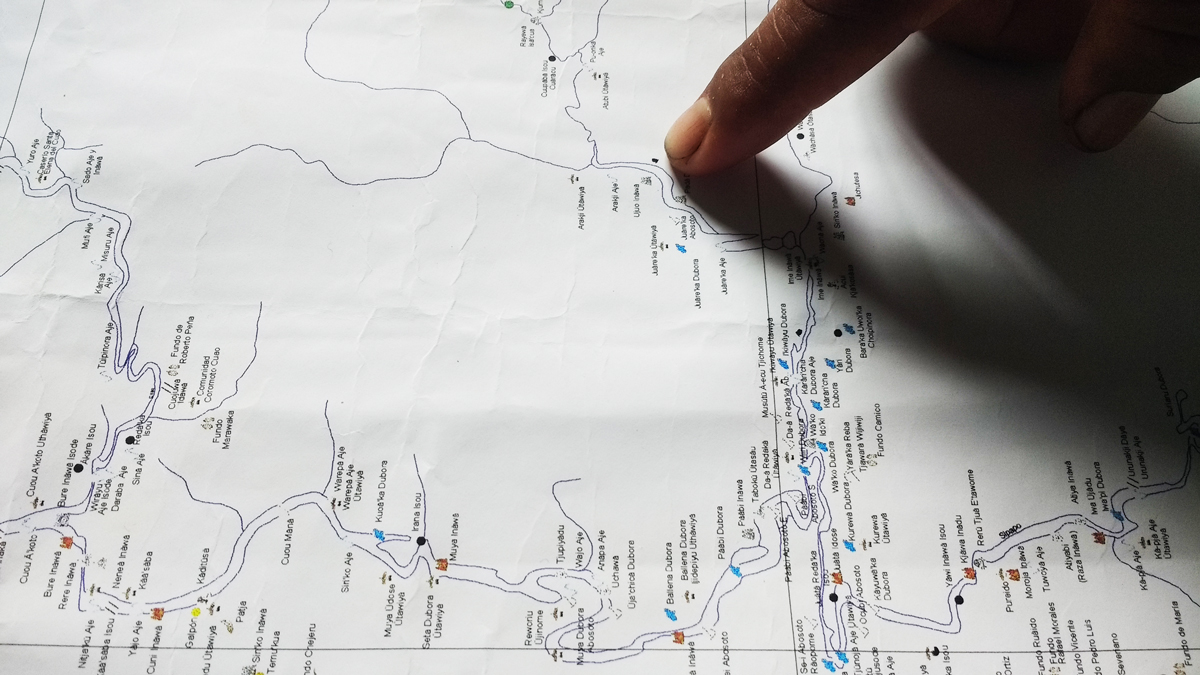

The February 2021 attack targeted a guerrilla camp on the outskirts of the community of Santo Rosario de Agua Linda, an Indigenous community of 300 inhabitants about 45 minutes south of Puerto Ayacucho, capital of Amazonas state. It was carried out by troops from the Army's 52nd Jungle Infantry Brigade, with about 170 troops. On the part of the Air Force, the Hongdu K-8W Karakorum training and tactical attack aircraft acquired from China in 2010 had their baptism of fire.

Image by Zodi Apure. Venezuela, 2021.

According to the military report, six people from the camp were killed in the assault, including the young Jiwi girl from the Coromoto community, located on the southern highway axis of the state, a road that leads to the port of Samariapo, the starting point for river transport to the interior of the Amazon. According to official information, the Indigenous girl had joined the insurgent ranks.

The transformation of the area, usually a tourist hotspot, into a theater of war operations, has been the culmination of a process initiated in 2016.

N.G., an inhabitant of the neighboring community of Botellón de Agua Linda, remembers the day of the attack well. It was a Sunday at ten o'clock in the morning, in the middle of a religious ceremony in the community hall. First the planes flew overhead, "then came the shots and an explosion," he says. The bombing went on for three days.

Emiliano Mariño is the captain or cacique of Santo Rosario, the community affected by the military operation. The local economy depends on the production of cassava and mañoco, two traditional preparations of cassava. His countrymen are Jiwi, a people also known by the Creoles as Guahibos, whose domain extends from the Llanos of eastern Colombia to the right bank of the Orinoco in Venezuela.

Leaning over the stove, while stirring the grains of the fiber extracted from the bitter yucca to turn it into flour, Mariño tells how the guerrillas arrived in 2016, set up a large camp on the slopes of the mountain and remained there for five years.

"At first we saw men dressed as soldiers walking through the streets of the community to the mountain, but we assumed they were Venezuelan soldiers," he says. The confusion sounds plausible: just four kilometers from the Indigenous settlement, on the main road that connects to Puerto Ayacucho, there is a command of the Bolivarian National Guard.

One day, says Mariño, a uniformed man who identified himself as a member of the FARC arrived at his house. "He told us that they needed to stay hidden in the jungle because their government was after them to kill them, that their presence was not going to alter the dynamics of the community and that, on the contrary, they wanted to support us with security and that we could trust that they were not going to interfere or abuse the women, nor with the conucos," referring to the peasants' survival crop plots.

And indeed, five years of peaceful coexistence went by, interrupted only by bombs.

Enlistment of young people

The forced recruitment of minors and Indigenous people is not news in the context of the Colombian internal war. But in Venezuela, nothing similar had been recognized. Until now.

"Here there are boys as young as fifteen years old who have gone to work with the guerrillas," says A.Q., a 23-year-old mother who works in a store located on the banks of the Orinoco River, at the crossing of the barge that connects Puerto Nuevo — a sector of the municipality of Atures also known as El Burro — with Puerto Paez, in the State of Apure.

Together with his mother, A.Q. runs a business that used to sell groceries and food, but due to the increase in the price of subsidized gasoline in Venezuela and the supply failures in the southern states of the country, he had to switch to the clandestine sale of gasoline from Colombia. An activity that has become a source of livelihood for many in the entity.

"Most of the businesses in El Burro work with contraband gasoline. Buses coming from Ciudad Bolivar and Caicara pass through there loaded with bachaqueros, vendors who cross to Puerto Carreño to buy Colombian merchandise wholesale and then sell it in Venezuela. Yesterday three buses arrived," she detailed.

The young mother assures that in that passage from Los Llanos to the State of Amazonas "everybody knows who is who. We all know who the people of the bush are," she says, referring to the guerrillas. "They deal with you, with normal people, they don't ask us for vacuna [or extortionate protection money]. They are in their own world. But they do help. For example, if a woman has a sick child and she turns to them, they offer her economic support."

One of her sisters is 16 years old and is pregnant by a Venezuelan boy who joined the guerrilla ranks, she says. And a childhood friend also works for them.

"My friend was taken to Cabruta [a town on the north bank of the Orinoco, in the state of Guárico], where the women do the same as the men: they carry weapons, stand guard, wash, cook. I wouldn't do that. That's easy to get into, the hard part is getting out."

"The war came for me"

The mother of M.L. went searching for her at the guerrilla camp. She asked to speak to the commander-in-chief to demand that her daughter return to the community. It was not easy, said E.R., one of the girl's teachers, but the mother went to the camp determined not to leave without her daughter. She succeeded.

M.L. was, along with the young woman killed in the bombing and a third companion, one of three Indigenous women from the Coromoto community who chose to join the guerrillas. E.R., who taught her, is a teacher in a neighboring community called Rueda.

E.R. relates that he asked M.L. why she had taken the risk of going with the guerrillas. The answer that remained engraved in her memory does not seem to surprise her: "I thought that by working for them I could help my family, we are in great need," the teacher recalls the girl telling her.

A socio-economic survey conducted by the Delegation of the Indigenous Defenders Network in that community of Rueda, as well as in another nearby village, Platanillal (almost five kilometers west of Coromoto, M.L.'s residence), revealed that 80 of the 286 people who participated in the study had some level of malnutrition.

A.S., a Jiwi Indigenous man who lives in Platanillal and is part of the Defenders Network, explains that the absence of the State and the humanitarian crisis that plagues the country are the main causes of the dramatic situation in which the Indigenous communities live. And they cannot alleviate their needs even with traditional hunting and fishing because the presence of irregular groups in their territory has denied them access.

"The Indigenous people do not want to go to the conuco to fish because on the way they meet the guerrillas, they are afraid. The CLAP bag arrives, with luck, every two months," explains A.S. in reference to the government program for the distribution of food and basic food basket products at subsidized prices.

A report presented by the Amazon Research Group (Griam) in April 2021 warns about the massive displacement of Indigenous populations from Venezuela to Colombia. Indigenous people migrate mainly to the border departments of Vichada and Guainía. "Of the 34 communities of the southern road axis, six were completely abandoned, they all left," A.S. details.

"From the communities of Rueda, Coromoto, Platanillal and Brisas del Mar, we know that 350 Indigenous people migrated to Puerto Carreño, and 400 to Cumaribo [towns on the Colombian side]. Only between October and November 2020, an estimated 200 Indigenous people, young and old, have left the State by river," explains the Indigenous defender.

Sitting in a tiny office, Michelle Beath Zurfluh, secretary of the office of the Governor of Vichada, recognizes that the entity faces a problem with the migration of Indigenous people from Venezuela. She explains that the Jiwi are now completing a second exodus, as many had crossed the Orinoco years before to Venezuela.

Now, conversely, the children and grandchildren of these migrants are returning to Colombia. There, they occupy settlements with precarious dwellings made of zinc sheets, plastic and fabrics that do not have any kind of public services. According to data compiled by Griam, produced by the Secretary of Social Development and Indigenous Affairs of the Government of Vichada, there are 25 Jiwi settlements in the capital of this Colombian department.

Children of the guerrilla

Since the National Liberation Army (ELN) set up three camps in 2017 near Betania Topocho, a community inhabited by 1,200 Piaroa Indigenous people north of Puerto Ayacucho, things began to change in unexpected ways.

Over time, outsiders began to blend in with the community. They recruited Indigenous youths for menial jobs. Between one thing and another, as they struck up relationships with the local boys, they began to meet the single girls in the community.

"Little by little the young men began to talk like guerrillas, express themselves and behave like guerrillas," says J.S., a villager.

Some voluntarily joined their armies: "You could see them wearing the uniform and on many occasions they were armed.

The link between the guerrillas and the young people of the community took on another dimension, and began to normalize to a certain extent, with the birth of the first children resulting from relationships between irregular combatants and the Piaroa women of Betania. According to local testimonies, at least seven children of ELN members are now members of the community.

On one occasion, a uniformed officer was seen lining up in a special operation carried out in the community by the mayor's office of the Venezuelan municipality of Atures for the registration of a child's identity.

Divided in two poles — those who support the presence of the irregulars and even work for them, against those who reject it outright — in Betania Topocho there are already several community debates that have taken place to weigh and mitigate the impact that the newly arrived neighbors are having on their traditional ways of life.

One such situation occurred in August 2021. At that time a girl from the community was identified as an intermediary for arranging love affairs and intimate encounters between insurgents and Piaroa girls. The assembly demanded, unsuccessfully, that the guerrillas stay in their camps and never set foot in the hamlet again.

For J.S., the precariousness of daily life is only the emotional basis on which the guerrillas find sustenance to seduce the young people of the community. "They lend them weapons, hats, talk to them about a new life full of adventure, money and power. They take advantage of the immaturity of the minors," he laments.

The Conflict Responses Foundation (Core) asserts that simplistic narratives that these groups are only made up of those who have not laid down their arms in Colombia do not reflect reality. In its report The Faces of Dissidence: Five Years of Uncertainty and Evolution, published in March 2021, Core states that the dissident groups have largely been fed by new recruits. This would be true on both sides of the Colombian-Venezuelan border.

The Amazonas State Ombudsman's Office has a formal complaint for the recruitment of seven Indigenous people by FARC members in the Maroa municipality, in the southwest of the state. In the complaint, they point out as responsible for the alleged enslavement and extortion "illegal foreign miners and Colombian armed groups outside the law (FARC deserters), who exercise total control of the mining area of the Siapa River."

Relatives of the seven young men said that they "were taken with false promises and are not allowed to leave the mining areas," according to the document, registered in March 2021 in the city of Puerto Ayacucho.

The relatives went to the military posts, but received no support, according to the complaint. They had therefore to mobilize to the guerrilla camp and request that the adolescents be released, without obtaining a response. "We presume that these adolescents were recruited to work in mining areas. It is a case that we are just beginning investigations by the Ombudsman's Office," detailed Gumercindo Castro, responsible for the Ombudsman's Office in the State of Amazonas, at the time of the denunciation.

(*) This is the fourth installment of a series investigated and published simultaneously by Armando.info and El País, with the support of the Pulitzer Center's Rainforest Investigations Network and the Norwegian organization EarthRise Media.

(**) This report cites testimonies from personal sources whose names are given only as initials, even if they did not explicitly request the confidentiality of their names. The editorial staff of Armando.info decided to do so in order to avoid possible reprisals from the armed groups against these sources. When the names are not presented in this way, they are sources who have already been identified in previous publications.