To understand forest-use dynamics in Peninsular Malaysia, one must know how state governments – the sole authority on land use – perceive forests. This is Part 3 of Forest Files.

In August 2019, when then Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad launched a forestry exhibition in Kuala Lumpur, he took the audience down memory lane.

“At the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, as the Prime Minister of Malaysia back then, I made a pledge that Malaysia is committed to maintain at least 50 percent of our land mass under forest cover,” said Mahathir.

“Today, almost three decades later, I am proud to announce that we have not reneged on that pledge,” he said. (Reference #1)

Mahathir then cited Malaysia’s forest cover of 55.3% (18.28 million hectares).

Official forestry department data shows however that in 2019, Malaysia’s forest cover had slipped to 54.1% (17.85 million hectares) from 56.4% in 1992.

State authority

Whether forest cover would stay at or fall below 50%, however, is not decided by the Prime Minister or his federal government.

Rather, state governments hold sole authority over forests in Malaysia.

So, to make sense of forest-use dynamics in Malaysia, one must understand how state governments perceive forests.

Forests as a source of revenue

When approving logging rights or excising areas out of permanent reserve forests (PRFs), state officials often cite the need to develop the economy, generate revenue for the state and create jobs for the people.

In other words, state governments see forests as a source of revenue and opportunities for growth. This is valid.

State governments must pay staff and build infrastructure, and their only significant sources of income are derived from land and forests.

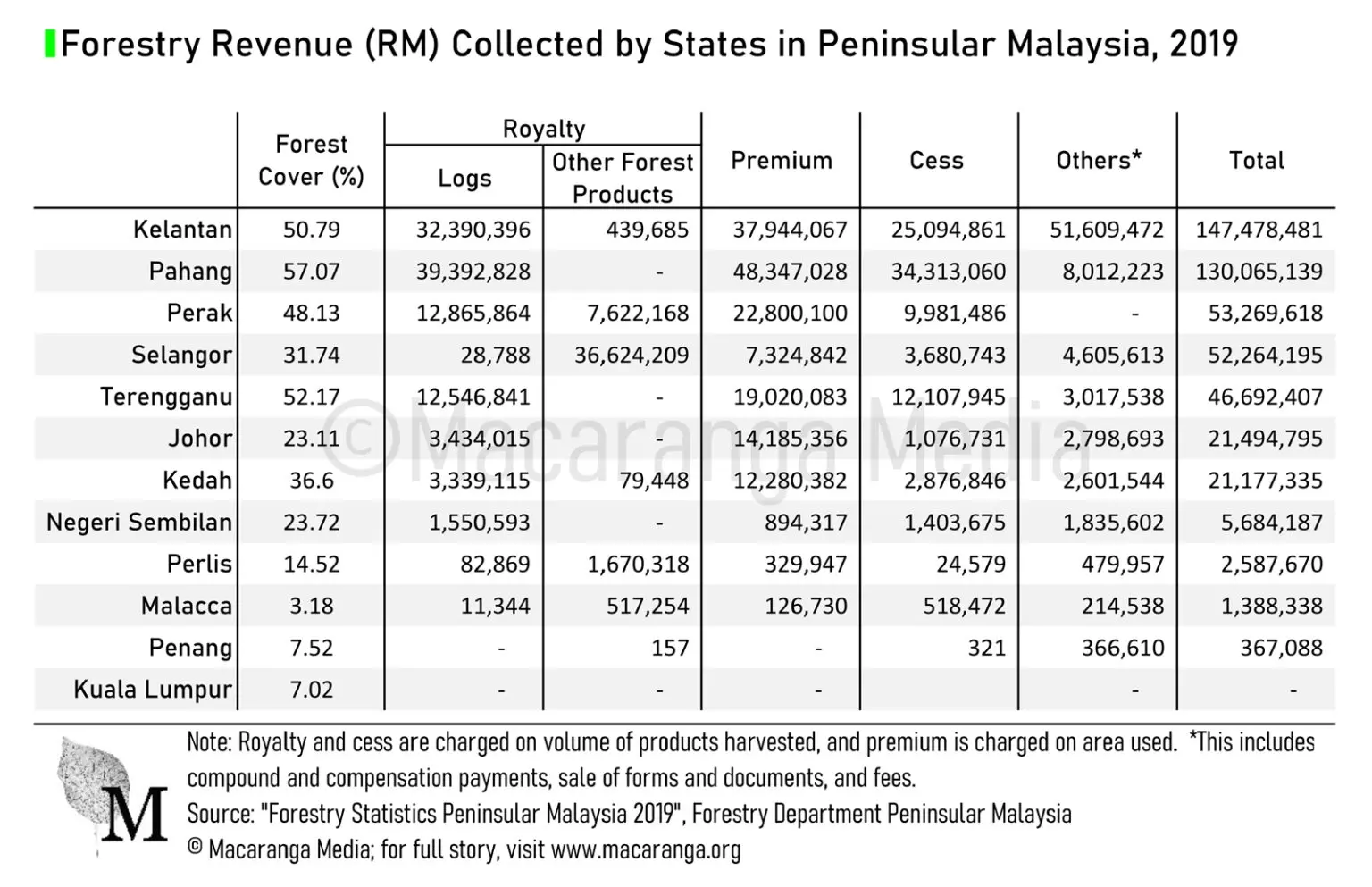

In Peninsular Malaysia, the focus of this In-Depth series, the states that generate significant forestry revenues are Kelantan, Pahang, Perak, Selangor, Terengganu, Johor and Kedah. (Table 1)

These states regularly receive between 20 and over a hundred million ringgit in forestry revenue yearly.

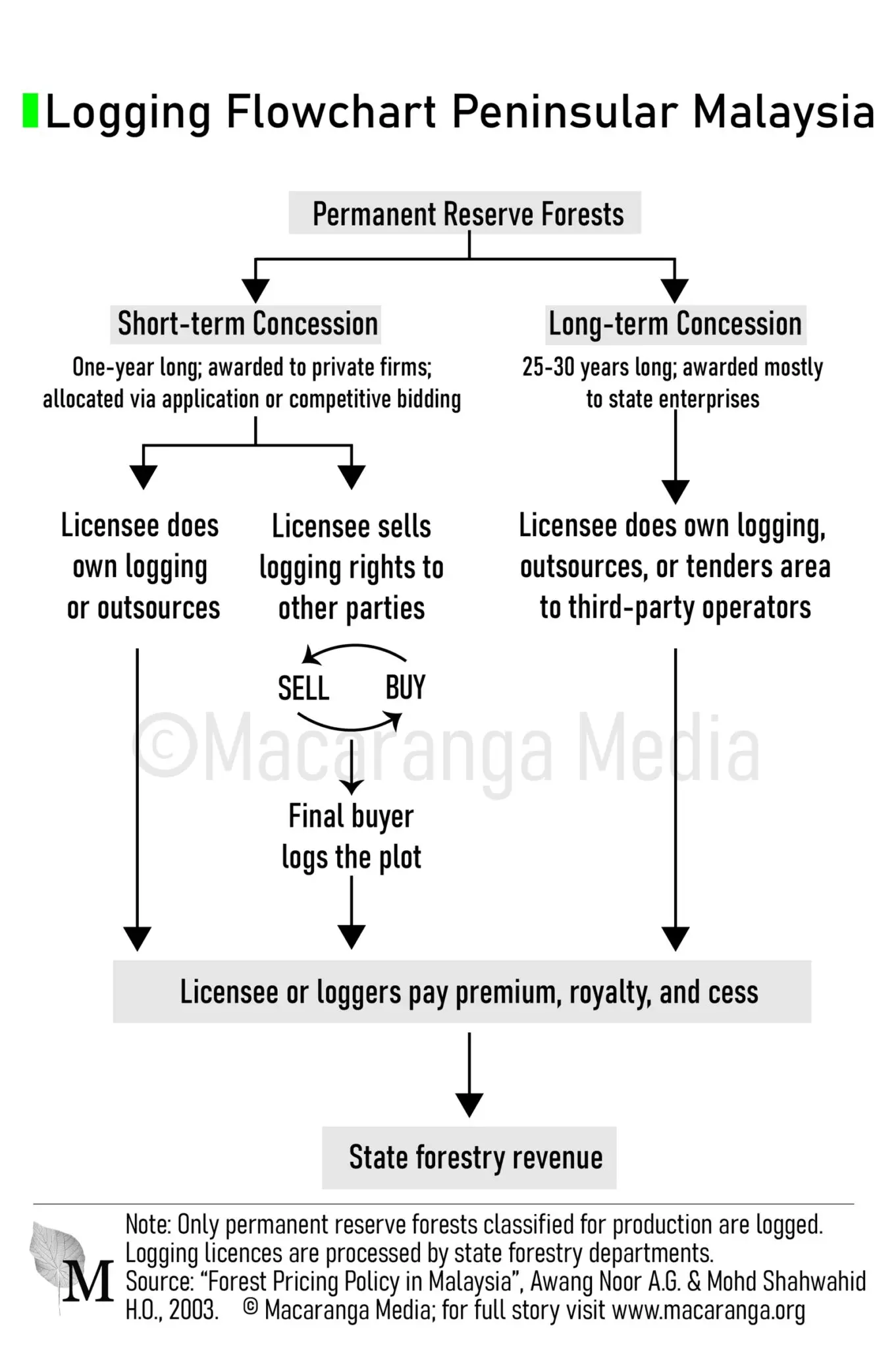

State governments earn revenue when they award logging concessions and licences for operators to harvest forests.

In PRFs, these concessions can be short-term, mostly for private firms, or long-term, for state enterprises. (Figure 2)

In return, state governments receive payments in the form of premium, royalty and cess.

Timber revenue was particularly important three decades ago before Malaysia industrialised.

Dato Wan Razali W.M., retired deputy director-general of the Forest Research Institute Malaysia, recalled that “many states in Malaysia in the 1970s depended on forestry for their income.”

An example is Pahang where forestry revenue has long been the second biggest revenue earner for the state government after land taxes, current forestry officers told Macaranga.

At the same time, Pahang continues to be the most forested state in Peninsular Malaysia.

Precious land

However, the value of a forest is not limited to its timber but the value of the land on which the forest sits, explained Balu Perumal, head of conservation at the Malaysian Nature Society. The NGO has been monitoring forest changes in Malaysia for decades.

This is because sustainable forestry management, which is compulsory in all PRFs, requires the state to leave intervals of 25—30 years between each round of logging.

These intervals let the forests recover from logging impacts and trees to grow large enough to be logged.

Steady income

But a resting forest generates no income for the state. So, state governments might be tempted to convert the forest into other land uses.

These include farms, oil palm plantations and even forest plantations of a single species, which Malaysia categorises as forest too (a controversial view also shared by the Food and Agriculture Organization).

By converting a forest into a plantation, for example, the state government collects rent annually from the operator, said Perumal.

“Nowadays, states will go and log the forest first, then convert it into plantation so they don’t need to wait another 30 years for the income stream.”

Hands tied

And because state governments depend on their land and forests for revenue, some of them have very few options if they do not log or clear forests, said Surin Sukuwan, who is a member of the IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA).

Making a pledge to not to log would be like “tying themselves up,” he said adding that forestry revenue could be “a matter of survival” for the poorer states.

“If I have to manage the state and I have to care about jobs and all that, and I don’t have many sources of revenue, I would be tempted to cut down forests.

“So, it’s the system that is the problem [and] not so much the individual Menteri Besar and politicians who are in power.”

A stumper in the ledger

There is something puzzling in the system though.

If the system restricts state revenue to largely land-based income like forestry – whether sustainable or clear-cutting – one might expect states to squeeze as much forestry charges as possible out of loggers.

But official forestry numbers suggest the opposite.

States set their own forestry charges and these differ from state to state, even quite widely.

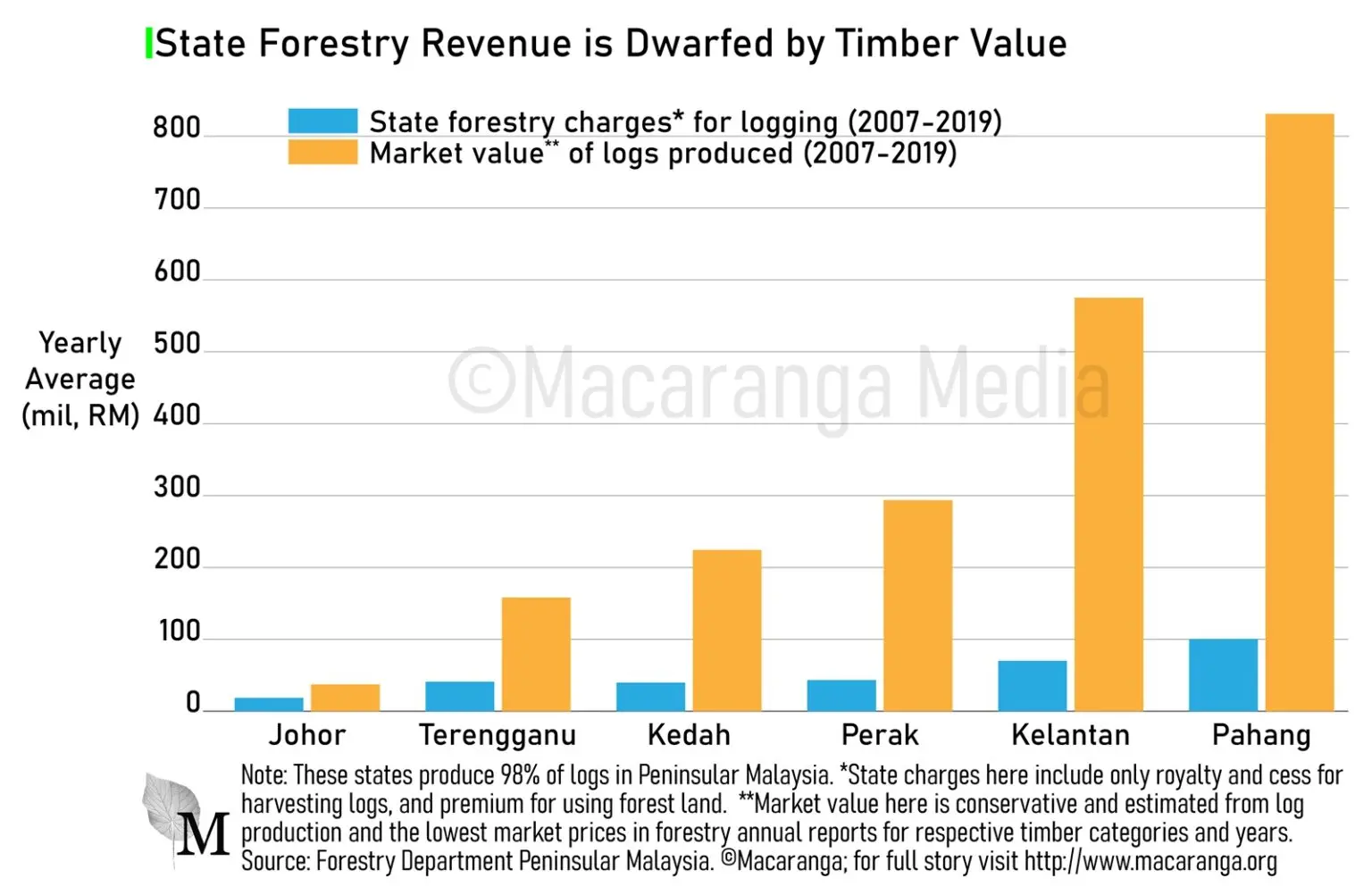

What is common though, is that state forestry revenue across the board is consistently much lower than timber value, what loggers are getting for the timber they sell in the market. (Figure 1)

This has been cited by independent studies on forestry data (Reference #4, #5).

One 2003 study (Reference #5) estimated that Pahang and Terengganu received on average 10% of the timber value, with much of the remaining 90% pocketed by loggers.

Costs off the books

However, loggers who spoke to Macaranga argued that the revenue gap is not as huge as it looks. They said that the official numbers do not reflect the reality of financing and running logging operations.

In fact, logging profits are eroded by upfront investments for machinery and to prepare forest logging plots to meet strict forestry rules.

Loggers also claimed that they incur huge “hidden costs” to buy logging rights from licensees to whom state governments generally first award the rights.

Macaranga could not locate these off-the-book costs in studies of forestry economics in Malaysia. There is a lack of more rigorous and thorough analyses to explain the apparent paradox in state governments relying so much on forestry revenue but asking for so little of it.

The paradox does, however, point to another way in which state governments perceive forests.

Forests as a source of power

In Malaysia, forests are not just natural resources but also political assets. Multiple studies of historical and current forest change in Malaysia have associated forest use with political power dynamics. (Reference #2, #3, #6-#8)

As the IUCN WCPA member Suksuwan mentioned, the finger is often pointed at state politicians, specifically the Menteri Besar, who leads the state governments.

(The state leader is called the Chief Minister in Penang, Melaka, Negeri Sembilan, Sabah and Sarawak, but state leaders will hereafter be referred to in this series as ‘Menteri Besar’).

The chief

In Peninsular Malaysia, the Menteri Besar is traditionally in charge of the land and natural resources portfolio(s). He also signs off on the gazette – official government notices – that finalise changes in forest classification and use.

Forest researchers and conservationists told Macaranga that the Menteri Besar has the final word on the fate of forests, One logger said that in forestry matters, they petition the Menteri Besar directly.

There has been one partial exception.

Between 2008 and 2014*, the then Selangor Menteri Besar, Tan Sri Abdul Khalid Ibrahim, who held the state’s land and natural resources portfolios, delegated forestry matters** to state executive council member Elizabeth Wong. Nonetheless, Wong told Macaranga that the final call on forest and land-use was still made by Khalid.

Swayed by external influences

Many of the forest stakeholders to whom Macaranga spoke, described how non-market forces influence logging. Specifically, this applies to the awarding of logging rights or licences by the state.

A veteran timber businessman in Peninsular Malaysia who asked to remain anonymous told Macaranga about “middlemen” – the people who buy and sell logging rights awarded by the state government.

These rights could change hands several times before they are exercised by loggers (the “Sell/Buy” step in Figure 2).

The voracious middle

The businessman was agreeable to states raising forestry charges. “We always tell the state government, you increase the premium [by] a reasonable figure, we don’t mind, but give [the logging license] directly to us.”

If this were to happen though, he said “the middlemen who want to take a big bite would not enjoy anything”.

Lim Teck Wyn has been a forestry researcher and consultant for two decades.

He zeroed in on the Menteri Besar.

“What incentives drive the Menteri Besar to protect forests, log them, or convert them to other uses?”

Political patronage

He pointed out that a Menteri Besar, through the conversion of forested land to some other use, could use this as leverage for political power.

“If he approves projects to his political cronies [or patrons], even if the state doesn’t make any money, even if the state obviously loses economically, he can still be entirely justified from a practical point of view to make the decision that ensures his political survival,” said Lim.

The Menteris Besar of Pahang, Perak, and Terengganu – three states with significant forest areas in Peninsular Malaysia – did not respond to Macaranga’s requests for comments.

Seminal studies by environmental sociologist Fadzilah Majid Cooke in the 1990s showed that the systems asserted by Lim and the veteran timber businessman have been in place for decades.

Helpful partners

In a series of interviews with forestry officers, loggers and sawmill owners in Pahang, Cooke revealed a tight and active network among state politicians and the timber industry players.

Chinese logging contractors would appoint as company directors “Bumiputra influentials”, who would then “ensure, through their political connections, that ‘their’ companies are in the running for bids on timber licenses,” wrote Cooke in a 1994 study (Reference #3)

“Contributions to party coffers especially at election times” could also help cultivate alliances with influential Bumiputera politicians, Cooke reported, quoting a “Pahang logging tycoon”.

Cooke did not respond to Macaranga’s requests for comments for this series.

Not so stupid

These assertions were refuted by Dato’ Lim Kee Leng, former deputy director-general of the Forestry Department Peninsular Malaysia.

He told Macaranga that political influences on the department’s processing of timber licenses and logging are “not significant”. (Lim spoke to Macaranga in May before he retired in July.)

“We have SPRM (the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission) breathing down our neck. You think we are so stupid to break the rules?” he countered.

Behind a veil

The fact remains though, that state governments headed by the Menteri Besar have the authority to use forest as they see fit – whatever their considerations may be. Their authority over forests is enshrined in law.

While nobody refutes the legality of this authority over forests, members of the public who are affected by the decisions, do question the lack of transparency with which it is exercised.

Besides the loss of biodiversity and the impact on climate change, communities who live by or inside forests – what more the wider public – are often caught unawares when the forests are logged or cleared for development.

Inclusive decision-making

This has been the bane of the most vulnerable segments of Malaysian society, indigenous communities, who lose not only livelihoods to deforestation but also culture and identity.

These are also the people who vote in these authority-holders.

How can citizens contribute to decision-making in forest matters? What can be done to better connect them with forest use and have their interests better inform state governments’ decisions?

Edited by SL Wong.

Next in Part 4: Involving the public in forest-use decisions.

This is the third of a four-part In-Depth Macaranga Forest Files feature on forest loss in Peninsular Malaysia. Read also Part 1: Forest loss: under whose watch and Part 2: Excision – the main threat to forests in Peninsular Malaysia.

Macaranga's Forest Files In-Depth series was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center’s Southeast Asia Rainforest Journalism Fund awarded to YH Law and SL Wong.

We thank the many foresters, researchers, timber trade stakeholders, lawmakers and citizens living near forests who helped us with our reporting. We also thank the six reviewers of an early draft of this series: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz, Chua Ern Teck, Nuradilla Mohamad Fauzi, Sharaad Kuttan, Theiva Lingam, and one who wishes to stay anonymous.