For the full interactive experience, click here to view this story on the Vox website.

Across the country, more than 27 million people have contracted the coronavirus, and 485,000have died. That’s the highest Covid-19 toll of any country and more than the coronavirus deaths in Italy, Germany, Australia, Japan, the UK, Canada, and France combined. It exceeds the US death toll in World War II.

It’s also an underestimate, and doesn’t account for all the people impacted by loss. If every American who died has left nine people grieving, as one study suggested, there are now more than 4 million Americans who have lost a loved one to the pandemic.

Death at this scale is difficult to comprehend, or visualize. To get a clearer sense of the shifting burden of Covid-19 deaths over time, Vox analyzed coronavirus mortality by age, region, and race from the past year, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Johns Hopkins University.

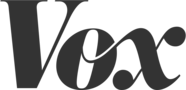

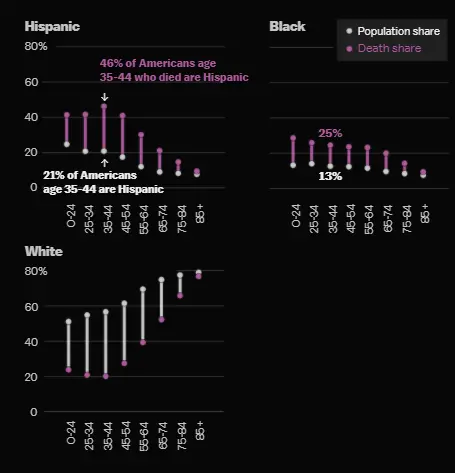

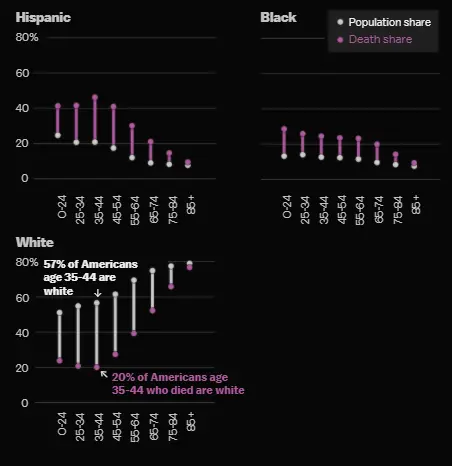

We found that while Covid-19 spared no group, it impacted certain populations more than others. Throughout the pandemic, people of color have consistently been disproportionately sickened and killed by the virus.They also died young: Of Covid-19 deaths in people under the age of 45, more than 40 percent were Hispanic and about a quarter were Black.

But what started as a health emergency concentrated in travelers, urban minority communities, and other crowded places (such as nursing homes and prisons) fanned out into rural areas of the country, leading to a surge in deaths among white people, too.

In the deaths, we saw how an “infectious disease became a universal issue,” said Boston University School of Public Health dean Sandro Galea. The extraordinary loss of life was also preventable, said Virginia Commonwealth University’s Steven Woolf, and a grim marker of “how poorly the US handled the pandemic.”

By the winter of 2020, the virus was spreading broadly in every state, and largely by people younger than 50. Still, disparities in lives lost have persisted.

In absolute terms, the death rate among white people rose significantly, while the rate among people of color dropped slightly. This was a trend we found in communities across America as Covid-19 spread.

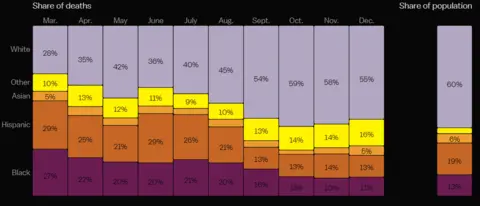

Deaths shifted from diverse counties to those with a higher share of white people

Experts attribute the change to the evolving geography of the virus — a result of the failure by states and the federal government to curtail transmission.

At the start of the US outbreak, coronavirus cases — and deaths — were concentrated in a few cities, which have large numbers of people of color who are more likely to do essential work. “The impact of Covid-19 was limited to New York, and to a lesser extent Detroit and New Orleans,” said Dartmouth health economist Jonathan Skinner, “and in particular among people who had to commute by public transportation to service-sector jobs.”

Many Black and Hispanic people soon contracted the virus and died at very high rates — an estimated 118,000 in 2020 overall.

By October, some of the most sparsely populated areas of the country — Wyoming, the Dakotas, Nebraska — were grappling with America’s worst outbreaks. The relative share of deaths among white people started rising.

“The politics of 2020 led governors in [these] parts of the country to be less aggressive in dealing with the virus or actively discourage public health safeguards,” Woolf said.

At the same time, more states adopted face-mask orders and other safety measures. Mask mandates helped bring case numbers down, and may have saved the lives of some essential workers.

The result: In August, Black people died at 2.5 times the rate of white people. By November, the rate was 2.2. In early February, it was 1.5.

But minorities were disproportionately affected by the virus in every month of 2020. They were also much more likely to die young.

“We would have otherwise expected them to live decades,” said Julia Raifman, an assistant professor at Boston University School of Public Health. Images courtesy of Vox.

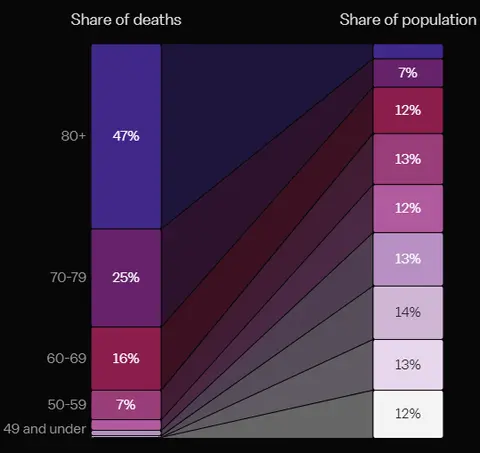

The data also reveals that regardless of race or geography, there is one group that has consistently experienced an extraordinarily high risk of death: the elderly. Age remains the greatest predictor overall of who lives after infection with the coronavirus and who dies.

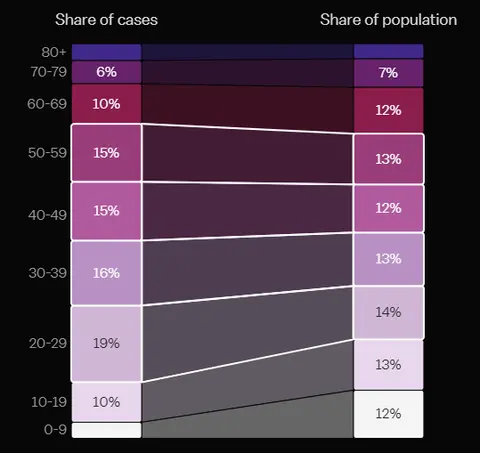

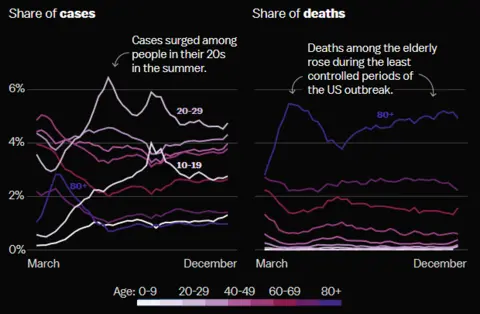

In March through May, people age 80 and older had the most confirmed cases per capita (although testing for much of this time was limited). By June, that burden shifted to younger people.

The summer case surge in young people was followed by a winter uptick in elderly deaths

So the people the least likely to die from the virus, maybe unknowingly or maybe because of carelessness, very often passed it on to those at the greatest risk of death.

That seems to be the pattern of the pandemic, how SARS-CoV-2 went from being a distant threat in China to a global tragedy: People who thought they wouldn’t be impacted, or who couldn’t protect themselves, passed the virus on, and on, and on.

They were enabled by a White House that denied science and downplayed the severity of the disease — and states that acted too slowly, politicizing public health instead of protecting it.

The pandemic isn’t over.

It’s not far-fetched to suggest the American death toll could rise to 750,000 or 1 million this year.

To prevent more needless suffering, we need to heed the lesson of the Covid-19 deaths in 2020: “The health haves cannot keep ignoring the health have-nots,” Sandro Galea said. “Because everyone is susceptible to Covid, the fact [that] higher-risk groups exist makes everybody vulnerable.”

Special thanks to the health experts who shared feedback on this story: Alyssa Bilinski, Sandro Galea, Julia Raifman, Jonathan Skinner, Daniel Weinberger, and Steven Woolf.

Methodology

Vox calculated the age-adjusted share of coronavirus deaths by racial and ethnic groups using the case surveillance data reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from February through December in 2020. We then standardized the death counts across age groups for each racial and ethnic group using 2019 population estimates from the US census.

White people are overrepresented in the older population, who the virus affects the most. The age-adjusted shares are a better representation of the risk of deaths for the overall population of various racial and ethnic groups; without adjustment, the relative shares of deaths show less disparity among these groups. Our calculations are based on data from deaths with specified race and ethnicity information, which are 77 percent of the total deaths in the case surveillance data.

Because of the incomplete race and ethnic information reported by jurisdictions, it is not yet possible to compute accurate death counts and death rates for demographic groups on the national level over time. This analysis does not solve the problem. Instead, we investigated the relative share of deaths across groups.

For the deaths by county analysis, Vox took county mortality data from Johns Hopkins University and county racial and ethnic composition data from American Community Survey 2014-2018. We then sorted the counties by their share of nonwhite population into 10 groups of equal counts and computed the deaths per capita for each county group over time.

The deaths by race and age groups analysis is based on data from the National Center of Health Statistics at the CDC between February 2020 and January 2021. The age analysis is based on case surveillance data and the 2019 population estimates from the US census.

Credits

Editor — Eliza Barclay

Visuals Editor — Kainaz Amaria

Design — Amanda Northrop

Copy Editors — Tim Williams, Elizabeth Crane

Engagement strategy — Lauren Katz

This project was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

COVID-19 Update: The connection between local and global issues–the Pulitzer Center's long standing mantra–has, sadly, never been more evident. We are uniquely positioned to serve the journalists, news media organizations, schools, and universities we partner with by continuing to advance our core mission: enabling great journalism and education about underreported and systemic issues that resonate now–and continue to have relevance in times ahead. We believe that this is a moment for decisive action. Learn more about the steps we are taking.