View the full interactive presentation on the TIME website.

On the southern crest of the unscathed Amazon rain forest, a storm inundates a wooden shack just off a sodden mud road. Inside, Antonio Bertola sits clutching a $1 beer under a painting of the Virgin Mary, his face ruddy and his clothes tatty from a lifetime of work on the land. The frontier town of Realidade is a mere speck on a changing map. To the north stretch hundreds of billions of trees and more than 1 million species never charted by man. To the south the muddy trail of human conquest reaches back for centuries. In a bittersweet tone of voice, Bertola recounts how his family of migrants had hungered for prosperity, security and, most of all, land to call their own.

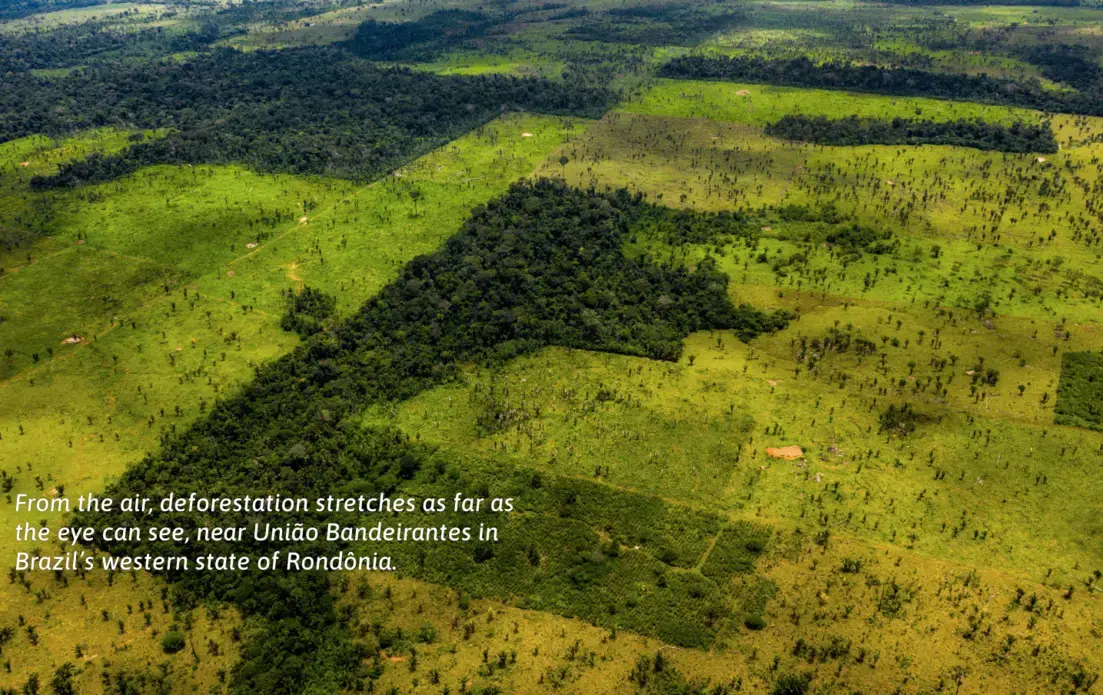

Five decades ago Brazil incentivized millions of its people to colonize the Amazon. Today their logging yards, cattle enclosures and soy farms sit on the fringes of a vanishing forest. Powered by murky sources of capital and rising demand for beef, a violent and corrupt frontier is now pushing into indigenous land, national parks and one of the most preserved parts of the jungle.

Brazil’s new President, Jair Bolsonaro, an unapologetic cheerleader for the exploitation of the Amazon, has the colonists’ backs; he’s sacked key environmental officials and slashed enforcement. His message: the Amazon is open for business. Since his inauguration in January, the rate of deforestation has soared by as much as 92%, according to satellite imaging.

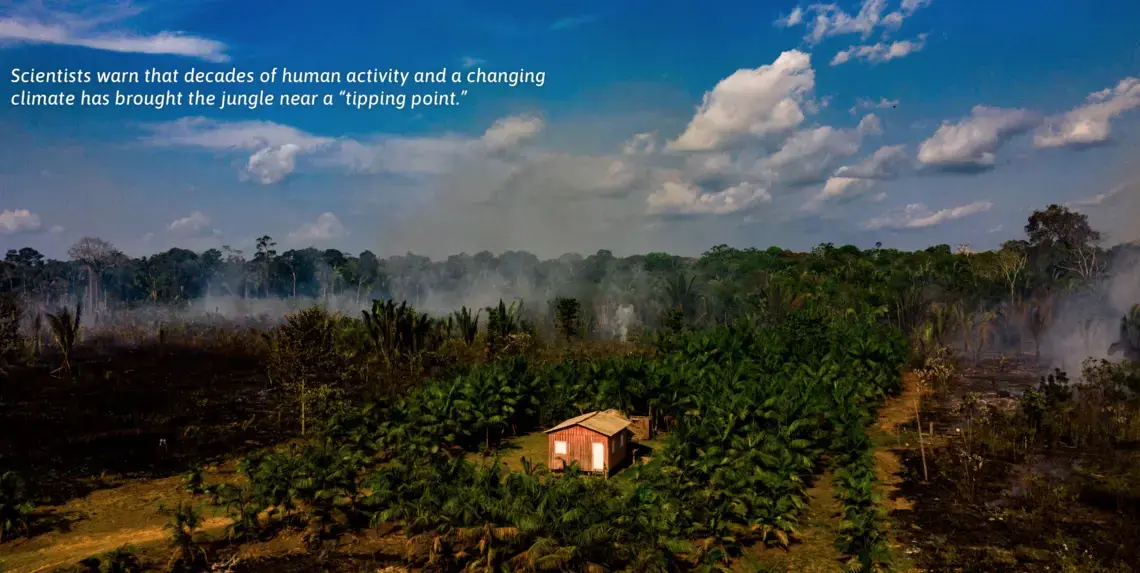

As human activity in the Amazon ramps up, its future has never been less clear. Scientists warn that decades of human activity and a changing climate has brought the jungle near a “tipping point.” The rain forest is so-called because it’s such a wet place, where the trees pull up water from the earth that then gathers in the atmosphere to become rain. That balance is upended by deforestation, forest fires and global temperature rises. Experts warn that soon the water cycle will become irreversibly broken, locking in a trend of declining rainfall and longer dry seasons that began decades ago. At least half of the shrinking forest will give way to savanna. With as much as 17% of the forest lost already, scientists believe that the tipping point will be reached at 20% to 25% of deforestation even if climate change is tamed. If, as predicted, global temperatures rise by 4°C, much of the central, eastern and southern Amazon will certainly become barren scrubland.

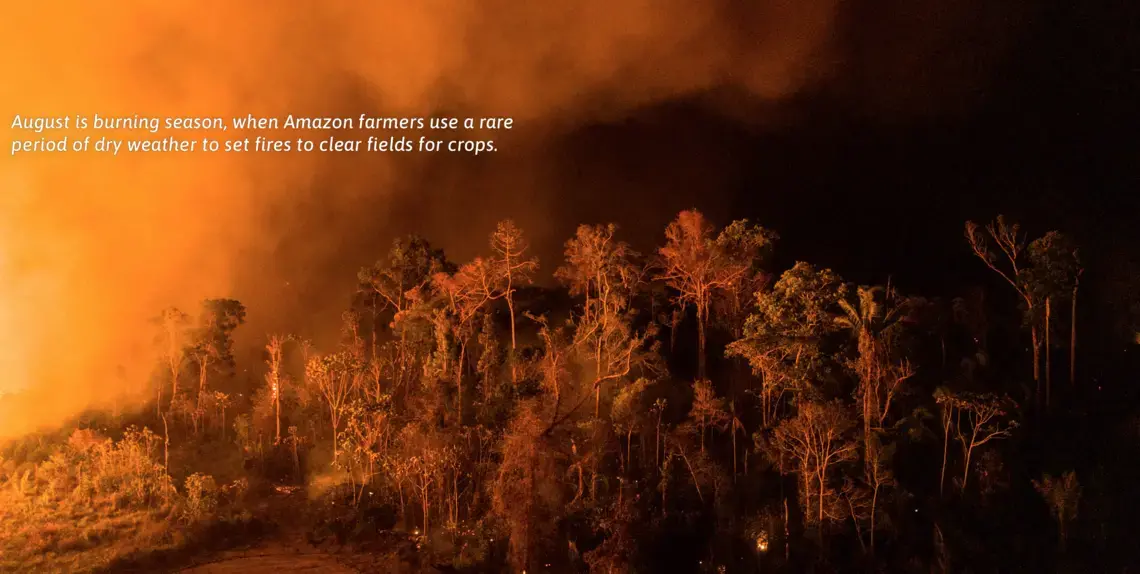

The fires that raged across the Amazon in August helped illuminate something the world can no longer ignore. Inside the crucible of this ancient forest, relentless colonization is combining with environmental vandalism and a warming climate to create a crisis. If things continue as they are now, the Amazon might not exist at all within a few generations, with dire consequences for all life on earth.

To understand what is truly happening to the world’s largest rain forest, TIME journeyed thousands of miles by road, boat and small plane this year to the front lines of deforestation. We spoke to loggers, tribespeople, environmentalists, ranchers and scientists. Despite growing outrage and threats by Western leaders to withhold trade with Brazil until Bolsonaro reverses course, on the ground we discovered the battle for the Amazon is close to being lost. The emboldened forces of development are running without restraint, and the stakes for the planet couldn’t be higher. As the official formerly responsible for Brazil’s deforestation monitoring, Ricardo Galvão, who was fired in August for defending his data on tree loss, told us, “If the Amazon is destroyed, it will be impossible to control global warming.”

The Amazon is 10 million years old. Home to 390 billion trees, the vast river basin reigns over South America and is an unrivaled nest of biodiversity. From blue morpho butterflies to emperor tamarins to pink river dolphins, biologists find a new species every other day.

The first humans migrated to the Amazon from Central America about 13,000 years ago. Up to 10 million tribespeople lived in fortified settlements, creating ceremonial earthworks, and cultivating fields and orchards. The Karipuna tribe roamed one enclave just south of where the Madeira River splinters into its tributaries amid rapids and waterfalls, in what today is the Brazilian state of Rondônia. The mouth of the Amazon sits 1,000 miles to the northeast. To the west and north the forest stretches into Bolivia, Peru, Colombia and Venezuela.

The European colonization of the Americas from 1492 saw settler plantations advance across the New World, bringing deforestation on a vast scale for farmland, firewood and houses. By the early 20th century, the world had lost trees that would have covered the Amazon rain forest at least once over, but its rain forest remained largely intact. Not so its inhabitants. As with many of the more than 300 tribes that survive in Brazil, contact with outsiders decimated the Karipuna’s numbers through illnesses such as measles and flu.

When the matriarch of the clan, Katicá Karipuna, was born about 70 years ago, her father led the only surviving faction of the Karipuna, which was still isolated from the wider world. Speaking with a soft lilt in her native language, she recounts that in those days, the birth of a girl caused celebration: the tribe would dance for days to the music of bamboo flutes to hail its endurance.

The 20th century saw more global tree loss than the rest of history. The Amazon, with vast mineral riches under its soil, finally came under threat. In 1964, Brazil’s military dictatorship took power and decreed the “empty” jungle was a security risk. It went on to create the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA) to conquer the forest and make it an agricultural stronghold.

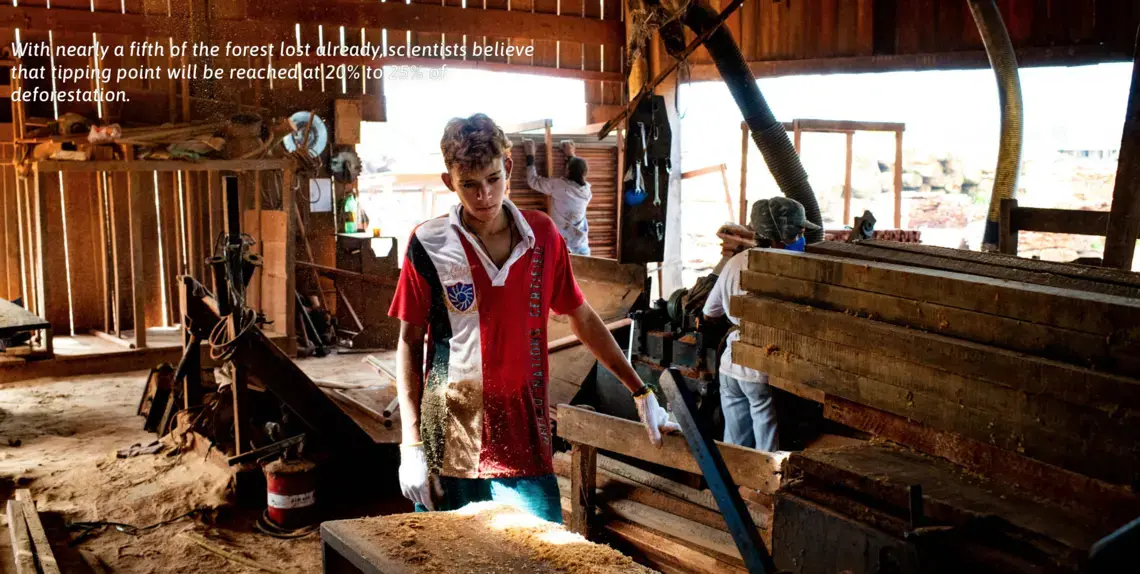

In the early 1970s, the government ran television ads for a new mecca of cheap land—and freedom. Bertola and his family, farm laborers descended from Italian immigrants to the south of Brazil, joined millions flooding northward on newly built highways. “Everyone had the same dream,” says Bertola, now 52. “It just meant deforesting it all.” Men like Bertola are the forward cavalry of deforestation. Where main roads are built, hundreds of makeshift logging tracks splinter off in a fish-bone pattern. The land is demarcated, often illegally, and lots are typically sold for a few hundred dollars by grileiros, or “land grabbers,” to poor farmers, who raze the forest and build communities.

Over time, electricity and phone lines arrive, and the jaguars that threaten the cattle disappear from the landscape. Once infrastructure is in place, wealthy tycoons buy up the land to build cattle ranches or vast fields of soy. Bertola and those like him track the frontier northward into the virgin forest.

Once in motion, expansion is relentless. In Brazil—one of nine countries in the Amazon basin—an area larger than Texas has been cut. Here in the frontier state of Rondônia, ranching is king, much economic activity is illegal, and state agents are bought off or outmuscled. Agribusiness in Brazil generates nearly a quarter of the country’s GDP, and the Amazon alone has over 50 million cattle.

For the Karipuna, the 20th century arrival of outsiders spelled further tragedy. The government sent an expedition into the forest in 1976 to find and assimilate the tribespeople, who—innocent and bare-chested—reacted joyfully at the moment of contact, dancing and holding hands with the outsiders.

The delight did not last. Katicá’s voice drops with sadness as she explains that over the following months and years, she watched her husband, parents and other family members die one by one after being exposed to new illnesses. The survivors tried to flee into the forest, but only eight survived.

In 1998, the few surviving Karipuna were granted a protected territory about the size of New York City. Indigenous land makes up 23% of the Brazilian Amazon and is a bulwark against deforestation. It binds the tribes to the fate of the forest—if one dies, the other likely will too. The next year, a few settlers placed a marker at a spot deep in the forest just a few miles to the west of the Karipuna’s territory. Early arrivals used rifle barrels to shoot pool, and sometimes each other. They christened their town União Bandeirantes, after raiders from Brazil’s past who hunted for gold and enslaved tribes. United by hardship and a sense of destiny, the newcomers held church services in the open air. “Since we arrived, we understood our town to be a door God opened to bless us,” says local pastor Arnaldo Bernardinho.

Early in the new millenium, due to international pressure, Brazil got serious about stopping deforestation. That was felt keenly in União Bandeirantes. The authorities tried to evict the settlers and, when that failed, raids by the federal environmental regulator, IBAMA—along with the army—fined nearly every farmer in the settlement. One rancher, Edgar Gonçalves de Oliveira, says he was fined $40,000 but has no regrets. “I’m sure if you were in my shoes, you would have done the same,” the 50-year-old told the IBAMA agent who fined him. “On the other hand, if I were in yours, I’d also be here doing your job.” Even though the government rarely succeeds in collecting the fees, a fine can prevent the recipient from getting loans and provoke aggravation. Such moves worked: deforestation fell 83.5% from 2004 to 2012.

Yet the numbers crept upward once again as protections were relaxed. As the country fell into its worst ever recession in 2014, and amid a huge government corruption scandal, Brazilians became antagonistic to the established order. The ground was fertile for Bolsonaro, then a Congressman known mainly as a reactionary agitator who glorified the dictatorship. He ran for President as an outsider in 2018, his stated ambition to turn the Amazon into Brazil’s “economic soul,” giving free rein to agribusiness giants, mining corporations, and developers big and small. Not one “square centimeter” of indigenous land would be designated if he became President, he said. Bolsonaro won 79% of the vote in União Bandeirantes in the October election. Soon after his inauguration, an empty logging truck without license plates trundled down a dirt road in União Bandeirantes, in the predawn gloom of a February day. A few days later, deep in the Karipuna’s forest, the sound of a chainsaw was unmistakable. Ancient trunks next for the chop had been daubed with paint, and tire marks were rutted into the soil. Illegal loggers had been there minutes before.

Seen from the air, the Karipuna land is an emerald tapestry. But on every side of it, the forest is gone. Now, vast tracts of their territory are also being deforested, despite strict federal protections. The implications are grave. Much of Brazil’s remaining forest exists in reserves.

Since coming to power in January, Bolsonaro has been ruthless in gutting protections, intervening to block an IBAMA operation against loggers in Rondônia, firing 21 of the agency’s 27 state heads and creating a new body to pardon environmental fines. Across the Brazilian Amazon in recent months, tribal lands and national parks have been invaded like never before. “It’s very sad, outrageous, to watch all the effort made over so many years by different governments being destroyed,” says Marina Silva, a former environment minister who pioneered the fall in deforestation.

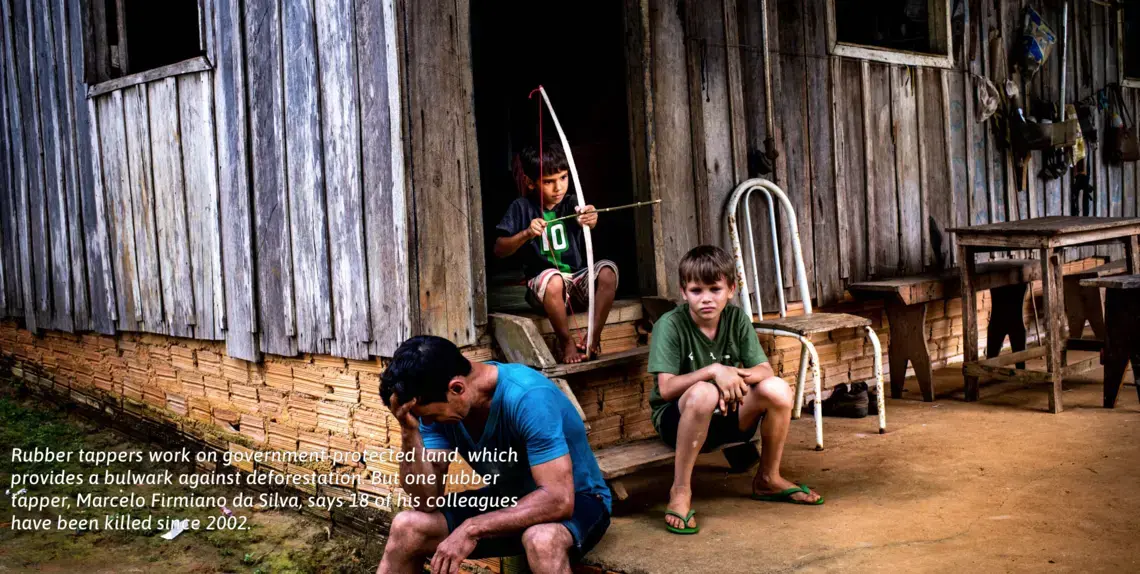

The Karipuna were already under threat. Last year, the equivalent of 70,000 tennis courts was razed. When TIME visited in February, the tribe felt isolated and fearful the new President would hasten their demise. “We are surrounded,” Katicá said, gesticulating toward the settler town. “They are already on our territory. This is how they will arrive to exterminate us.” Her fear is not misplaced. The Amazon is riven by deadly conflict over who controls the land. More than 1,300 people have been killed in such conflicts since 1985, and Rondônia is the crucible. There, hired gunmen ensure the interests of the powerful. Nilce de Souza Magalhães, a campaigner against a hydroelectric dam under construction in the state capital, was found dead beside the Madeira River. Adelino Ramos, a peasant leader in favor of land reform, was executed at a market in front of his children. And in western Rondônia, 18 rubber tappers have been killed since 2002 in protected reserves. “Today the fight has got so much worse,” says their leader Agenor Firmiano da Silva. “We are on the verge of giving up.”

Technically, the law is still on the forest’s side. Indeed, the federal police raided União Bandeirantes in August to arrest illegal loggers. But with just five Karipuna families on a vast territory coveted by many, campaigners believe any ground ceded here could prove to be the first domino in an assault on the very principle of protected reserves. “If the Karipuna territory falls, it will be the first of many,” says Danicley de Aguiar of Greenpeace.

Just down the road, 20 years after its beginnings as a gritty frontier, União Bandeirantes is showing signs of nascent wealth. Painted bungalows with neatly tended gardens dot its rural outskirts, and pastures home to nearly a quarter of a million cattle stretch to the horizon. At the evangelical church, in a chapel with 113 pews made from the trunk of a single angelim tree, the congregation weeps as a service reaches its climax. The pastor, Bernardinho, thanks the Lord the town is flourishing. “Now,” he says, “we are prosperous.”

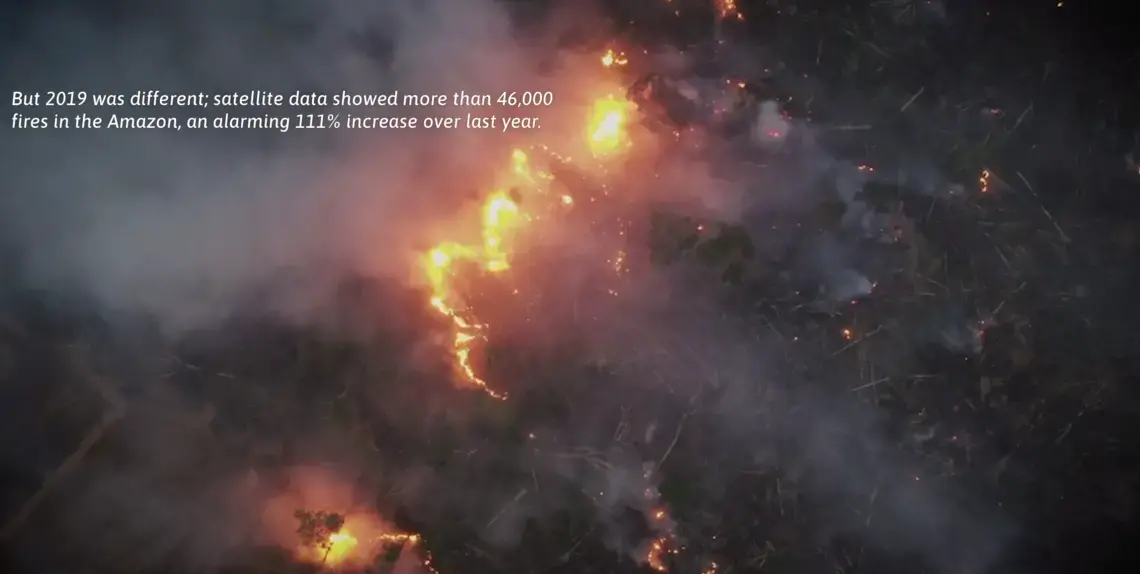

As the seasons changed, crimson fires lighting up the night sky across Rondônia showed that prosperity will always come at a price. August is burning season, when Amazon farmers use a rare period of dry weather to set fires to clear fields ready to plant crops. But 2019 was different; satellite data showed more than 46,000 fires in the Amazon, an alarming 111% increase over last year.

Initially Bolsonaro was unflustered. After all, he had already dismissed preliminary 2019 deforestation figures as “lies” and sacked Galvão, the head of Brazil’s space agency, INPE, for defending the data. “The President’s accusation was very serious,” says Galvão. “Scientists felt thrown into hell.” Those preliminary INPE figures suggest a 92% increase in deforestation over the first eight months of 2019 compared with the same period in 2018. It is not yet clear if deforestation has returned to the heights of 1995 to 2004, but Bolsonaro’s support for unfettered development appears to have made an impact. “The whole environmental structure of the country is being destroyed,” says Paulo Artaxo, a Brazilian member of the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The fires sounded alarms abroad. French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel spoke out. At an event in São Paulo, Bolsonaro replied, to cheers, that the two “did not realize that Brazil is under new management.” He claimed developed nations were using an environmental agenda to “take over Brazil” for its natural resources. “Sovereignty of the region and its riches is what is truly at stake,” the President said in August.

Late that month, aided by rare atmospheric conditions, a vast plume of black smoke drifted from the Amazon and darkened afternoon skies as far away as São Paulo, over 1,700 miles to the southeast. As dramatic images of the blackout and fires proliferated worldwide, protests broke out across Brazil and in cities around the world. And after the G-7 leaders held emergency talks during their summit in France, Bolsonaro relented. “I have a profound love and respect for the Amazon,” he said in a televised address. “Protecting the rain forest is our duty.” He immediately dispatched warplanes and army units to Rondônia to fight the blazes.

Few are convinced he means it. “If the government believes we live on an island, we won’t succeed,” says Blairo Maggi, a billionaire tycoon known as the “soy king.” “He created an unfavorable environment for our exports.” France and Ireland have threatened to sink the E.U.’s trade deal with the South American trading bloc Mercosur unless Brazil resolves the “international crisis,” and Norway and Germany have halted donations to the Amazon Fund, the largest private investment in saving the rain forest. Congressman Alceu Moreira, the leader of the powerful agricultural caucus in Brazil’s National Congress calls European pressure simply “a commercial war.” He says, “Brazil won’t take into consideration the whims of those who seek to control us from the outside.”

At least 427 species of mammals live in the Amazon rain forest, but one now dominates in terms of raw numbers: the cow. Cattle farming accounts for up to 80% of deforested land. In 2018, Brazil exported some $6 billion worth of beef, more than any other country in history. While stringent supply-chain standards make Europe a difficult market for Amazon producers, countries in Africa and Asia—particularly China—are less discerning.

The law requires small farmers to maintain 80% of the forest on their land, but the penalties do not deter livestock farming. Oliveira, the rancher in União Bandeirantes, cannot legally sell his cattle owing to embargoes placed by the environmental regulator. Instead he sells animals at a discount to a middleman, who sells them to Frigon, the biggest slaughterhouse in the state, without a problem. Slaughterhouses often turn a blind eye to the source of cattle that arrives via third parties—a state of affairs the owner of Frigon, João Gonçalves, happily admits exists.

Striding confidently around his vast plant as a line of cow carcasses is gutted by white-clothed employees on his production line, Gonçalves talks with a lifetime of certainty about the benefits of expansion into the Amazon. His slaughterhouse will soon be the biggest in Brazil, according to the company, killing a cow every eight seconds. His company exports nearly 40,000 tons of beef each year to Hong Kong, Egypt, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Switzerland and Denmark.

Throughout the industry, accountability is scarce. The Brazilian company JBS, a global leader in beef production, has been fined millions of dollars for buying cattle from farms under embargo. American agribusinesses Bunge and Cargill are among the largest players in the export of 14.9 million tons of soy from the Amazon annually, used primarily as a livestock feed. They have also been fined millions for sourcing soy from off-limits areas.

For at least some working in the Amazon, the environment is simply irrelevant. “We came here to open up this region, so now let’s leave it? It’s not logical, is it?” asks Gonçalves, the slaughterhouse owner. “We came here to deforest, to clean,” he adds. “In the next 100 years, the Amazon will all be open. It’s a matter of time, right?”

Yet the consequences are now becoming apparent even to some of Bolsonaro’s supporters in União Bandeirantes. Oliveira, the rancher, says the stream at the bottom of his land has dried up. On the eastern edge of the Amazon, shrubland has emerged. And in deforested areas in the south, temperatures rose at more than double the global average.

With tens of billions of trees already gone, the region is warming fast. Droughts and floods are more common, and the dry season has grown by six days per decade since 1980. Trees play a crucial role in putting water back into the atmosphere, and their absence means less rainfall and higher temperatures.

Carlos Nobre and Thomas Lovejoy, leading authorities on the Amazon and climate change, believe all of it—deforestation, the fires lit by ranchers that spread hundreds of meters through forest, and the impact of global temperature rises—might soon push the rain forest past its tipping point. Current projections by the U.N. show the earth heading for heating of up to 5°C this century—far higher than the 2°C assumed by Nobre’s research. If that happens, that forest will be lost forever. “In 10 or 20 years, we will make a final diagnosis,” says Nobre. “If this process continues, it becomes irreversible.”

The forces set in play in the Amazon could have serious global consequences. The forest stores up to 120 billion metric tons of carbon, equivalent to almost 12 years of global emissions at current rates. If cleared, much of that will go into the atmosphere. That alone could push the global climate beyond safe limits.

The Amazon tipping point could also lead to a cascade of other potential climate tipping points. Forest dieback is strongly interconnected with other phenomena such as the melting of the Greenland ice sheet, which would cause sea levels to rise, and the degradation of frozen soil in the Arctic known as the permafrost, which would release greenhouse gases held in the ice as well as long-dormant diseases. Scientists believe that these changes combined could result in runaway global warming that humans would find impossible to reverse.

To avoid the worst-case scenario, the heart of the Amazon must be spared. Although 19.8% of the 1.5 million sq. mi. of the Brazilian rain forest has been conquered, mostly along its south and east, swaths of the west and center remain intact. But that might soon change. From the vanquished terrain of Rondônia, a decaying highway roves north into the forest. The BR-319 bisects the Purus-Madeira basin, one of the most preserved parts of the forest, where wildlife such as nocturnal two-toed sloths, woolly monkeys and teju lizards live undisturbed. The military inaugurated the highway in 1973 to connect Porto Velho, the capital of Rondônia, with Manaus, the largest city in the Amazon. Yet within a few years, the 550-mile road fell into disrepair, reclaimed by grass and weeds. Jaguars and anacondas would cross the asphalt, flecked with meter-wide potholes and rusting road signs.

Now the BR-319 is stirring again. On this road lies Realidade, which frontiersman Bertola has called home for the past six years. There, the lumberyards are opening fast and the telltale fish-bone tracks already mark the jungle. Today, Realidade has 21 evangelical churches and three chainsaw repairmen. It is a harsh life in the midst of the forest; the newly arrived face the threats of malaria, deadly snakes and persistent torrential rain. At times it feels like the forest is fighting back against the invasion. “Everyone who comes up this road comes with a dream to find wealth,” Bertola says with a sigh. “Here, they only find suffering. But we do not desist.”

Bertola, like around 5,000 fellow travelers in recent years, moved in anticipation that the BR-319 would be repaved. But, despite much debate, nothing was done, and the road deteriorated. In July, Bolsonaro committed to repaving the highway “with all certainty.” But paving the road will “transform the geography of deforestation” by creating easy access to an area of forest bigger than Germany and Holland combined, according to Philip Fearnside, a professor at the National Institute of Amazonian Research. Fearnside co-authored a recent study that shows paving the road and another highway, the AM-364, would lead to a 277% increase in deforestation in the region by 2050. “This highway will accelerate us toward the tipping point because it cuts in half a very rich water basin and an area of high biological value,” says Ricardo Mello, head of the World Wildlife Fund’s Amazon Program.

Those praying for the rehabilitation of BR-319 aren’t thinking about that bigger picture. Bertola builds houses for newcomers out of wood from the forest. He’s bought a plot deep in the jungle and plans to deforest half of it, build a cattle enclosure and buy livestock. He hopes Bolsonaro will help him achieve his goal of starting to earn from the land in 2028. By then, the logging boom will have subsided and cattle ranches will take over. Eventually, this too will become soy fields. Ultimately, Bertola says, he will put his family first.

But if the worst happens, it will be felt first by those forging livelihoods on the frontier. The decline in rainfall would parch farmland and cause widespread drought. Lower river levels would have a knock-on effect on boat transport, the fishing industry and hydroelectric power generation. If the tipping point is reached, the Amazon’s economy would be largely destroyed. But the wheels of expansion continue turning unabated. In February, near the foot of the BR-319, not far from where the asphalt turns to dust, the piercing sound of drills rings out over the forest. The metal frame of a new slaughterhouse is already taking shape next to the road.

In the Karipuna’s reserve, the once distant hum of chainsaws and gunshots grows louder. Katicá worries every day about the future. The invaders, she says, “do not understand that they are in a place that is not their own.” But it is the prospects facing her grandchildren that worry her most; she cannot imagine a future for them without the forest.

The tribal lands are her world, she says. As the sun glows through the branches in a clearing near her village, and spider monkeys scamper in the canopy above, her eyes remain alive with defiance. “If I die,” she says, “I die here.”