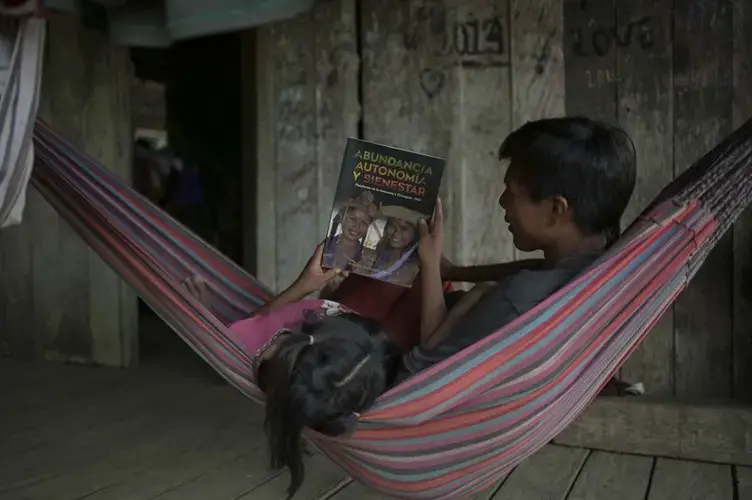

A handful of indigenous guards watch over the jungle to prevent a tragedy that their grandparents see in their dreams: the destruction of their "sacred houses", the hills. A young leader remembers the day that the tranquillity was disrupted in his community. When he learned that there was a 30-year license granted on his territory to extract coltan, one of the most scarce and precious minerals, used by the world's big technology industries when manufacturing cell phones, computers and electronic devices. In Africa, the Democratic Republic of Congo has the largest number of reserves of what is considered the new 'black or blue gold'. In Latin America, there are mines in Venezuela and Colombia.

The Timbó communities of Betania are multi-ethnic. They are inhabited by 23 families from seven indigenous groups with beliefs rooted in their natural environment. Living together in this community are the Desanos, the people of the lightning; Guananos, the people of the water; Sirianos, the people of the clouds; Cubeos, the sons of Kubai; Tucanos, the people of the toucan; Tuyucas, the people of the clay; and Barás, the people of the fish. They are all friends of nature, subsisting on fishing, hunting and gathering the fruits of the forest.

The community is surrounded by hills - which they consider their "sacred houses" -, and by streams, and flowing rivers. Timbó de Betania is in the middle of the Murutinga and Bogotá Cachivera settlements, 50 kilometres from Mitú, the provincial capital, at the end of the only road in Vaupés, known for its white sands and reddish clay. According to the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE) in this part of the country, the southeast of Colombia and on the border with Brazil, there are 37,600 people and 27 ethnic groups living together.

The houses are made of wood and have been built above ground so that their inhabitants can take care of the snakes and wild animals that roam around at night. In the community there is a school, a communal hut, a chapel and a maloca (an ancestral longhouse used by indigenous people of the Amazon).

At five o'clock in the morning, the sun's rays’ peek through sturdy trees and palm trees. You can hear the birds singing. At six o'clock, a bell rings. It is the call to the quiñapira, a traditional space where the community shares food (fish soup with chili). The indigenous people meet in the hut located in the centre of the village. The women bring broth and cassava, a kind of hard tortilla made from yucca starch.

Everyone has a plate, a bowl and a spoon in hand to receive the food. At seven o'clock, when they start feeling the heat, the children go to school, and the youngest ones, who are under five years old, go with their mothers to the chagras, a piece of land where they grow bananas, yucca, peppers, yams and fruit trees, such as pineapple. The men go fishing or to collect seeds. Some stay in the hut to discuss and attend to the needs of the territory.

At three o'clock in the afternoon they return to Timbó and go to the watering hole as a family. There, while the women wash their clothes, the children play naked in crystal clear water that runs between large earthy stones. The nights are silent and starry; in the sky the Milky Way can be seen in all its splendour and in the hut some people have lit candles. In the maloca, the grandparents meet, to revive their customs with prayers and legends.

That's the way it is almost every day, quiet.

However, they also have many needs. There is no drinking water. There's no energy. Even though there is an electric network, it has not worked since it was installed seventeen years ago. There is no health centre and there is a shortage of medicines. Some of the children, the youngest ones, suffer from malnutrition, their hair is fine, they are thin, and their bellies are swollen. Malnutrition is one of the problems facing the more than 350 indigenous communities in Vaupés.

And their natural resources are at risk of being exploited.

Rubén Darío Ardila Montalvo is thirty years old and a member of the Desano ethnic group, he is Captain of Timbó (this is how they call the main leader of the indigenous communities in that area of the country). He is well built, and his eyes are slanted and as black as the night. Together with several leaders they meet in the communal hut, which has walls and wooden benches. They talk about the threats to the territory, and Rubén shows on a map the sacred sites - hills, water sources and salt flats - that are in danger from mining.

The Captain remembers that in that same hut, a conversation was interrupted by a geological engineer with a Paisa accent in April 2017, he was tall and grey and demanded that they sign a document authorizing a license for the exploitation of minerals for thirty years.

“But how would we sign this without knowing what I’m going to sign”. I said: “Shame on you engineer, I am not going to sign a document blindly without any knowledge. Without authorisation I can’t sign this. What a pity!”, said a tormented Rubén.

Everyone was surprised. They didn’t understand why their territories were being given up for the exploitation of coltan, that is, to extract the minerals niobium, tantalum, vanadium and zirconium, or black lands. Most of the indigenous people were not even aware of these terms, they only knew that there was a man next to them who shouted at them about the existence of a contract.

A total of 2,004.08 hectares was granted as part of the license, out of the of the 3,896,190 - hectare Vaupés Indigenous Reservation. The former Colombian Institute of Agrarian Reform (Incora) established this reservation in 1982. The National Mining Agency (ANM), in response to a request sent by Agenda Propia, confirmed that the land granted for the 2,000 hectare concession is in effect under the name of Claudia Patricia Gómez González. On the ANM's National Mining Cadastre website, the name was registered in 2014.

This license is classified as medium-scale mining, because the exploration stage is in the range "greater than 50, but less than or equal to 5,000 hectares", as established by Decree 1666 of the Ministry of Mines and Energy in 2016, which regulates mining classification. To move up to the large-scale category would depend on the annual production reported during the mining stage.

Rubén returns to the map drawn by the community and points out the Abejorro Hill: "The license was granted at this spot between Murutinga and Timbó de Betania". He explains that it is about five kilometres in a straight line from Timbó and the area is a forest reserve and a shelter.

The indigenous people and the community centre claim that the license has been granted to a Spanish company.

Next to Rubén is Gladys Socorro Jaramillo García, a fifty-year-old leader of the Bará ethnic group. Gladys has dark brown eyes, coppery skin and a wide smile. She remembers the engineer's presence, and she says that he upset everyone.

According to her story, she was in the kitchen of her house, about 200 meters from the cabin, serving chicha (a drink made from yucca starch). When she heard the discussion, she ran out to find out what was going on: "He (the engineer) told us that it was for our own good, but after we complained to him, he told us not to bother him, that he had a document with permission to be here.”

At that time, the community was focused on the priests from the Community Centre, who usually accompanied food security programs and guided the indigenous people in the elaboration of their life plan (a route to recover their knowledge and community organization). It was precisely the appeal made by the priests that made the engineer respect the inhabitants, their collective rights and leave the hut.

The community started making claims against Rubén and other leaders.

“They pointed me out. They told me that I sold the territory for money, that I received thirty million, fifteen million. That's false," the Captain says.

In Timbó de Betania they think that the right to prior consultation was not respected because they did not dialogue with all the inhabitants of the three communities, Bogotá Cachivera, Murutinga and Timbó themselves. Apparently, there was a meeting with some indigenous people where they signed an agreement.

José Ernesto Uribe Suárez, who was a captain between 2005 and 2014, says that he learned that the miners held a meeting in Murutinga and an engineer came to the area to take coordinates, but at the time he did not know what these people were working on.

"They came with an engineer, as they negotiated. They had a big meeting and I think that's where they signed the document. According to people, most of them signed the document, which means that they are going to mine, so after five years, or six, this problem started to appear (...). From then on, a year later, they returned by force, they came with a big project, which was already done, already signed," says the former captain, calling for clarification of what happened.

The indigenous people are talking about their fears again. They fear that the arrival of the mining company will contaminate their rivers and, in a worst case scenario, force them out of their homes.

The vice-captain of Timbó, Luis Octavio González, 42 years old, worries that a pipe will be built in the area where the mining will take place, to supply the community. "The contamination would come all the way down from there, so that's why we are afraid, the ones who would be harmed would be us. What would we do without water, without fish, without animals," he wonders in anguish.

The community has heard that near Abejorro hill they are already mining, although it is not known if it is the company or illegal miners who are also extracting gold.

"People are saying that foreign people are coming in. Right now, they are not entering Timbó, but very close by," Rubén said, while recommending that his colleagues make other trips to verify this information.

Vaupés is rich in gold, silver, tungsten and black lands, like coltan, which has led to the arrival of miners after these resources; many people approach the territory using traps and gaining the trust of the natives. One case that has been heard in this region is that of the Canadian firm Cosigo Frontier. Ten years ago, it entered the heart of the Yaigojé Apaporis National Park and Reservation - a jurisdiction of the municipality of Taraira, very close to the Brazilian border - leaving behind divided communities after violating the prior consultation and the laws of origin of the peoples. The Ombudsman's Office reported, in response to a right of petition sent by Agenda Propia, that the activity of gold mining companies in this municipality caused "damage to the integrity and unity of the indigenous communities". Gold has been exploited in Taraira for more than 25 years, partly by traditional miners and partly by illegal Colombian and Brazilian companies. The extraction has caused irreversible environmental damage, its rivers are contaminated with mercury and its people today see the terrible consequences.

Now, in Timbo they are trying to avoid what happened in Yaigojé Apaporis. The indigenous people prefer to speak up so that their case is not silenced.

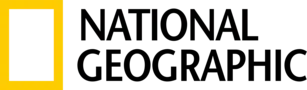

Since they know about the threat of mining, men and women are trained at the communal hut in rights such as prior consultation, and together with the grandparents and traditional authorities, they lead the way in defence of their territory.

At the end of the meeting with the leaders, Rubén confirms that he will continue to complain and seek help from State entities, the church and international organizations to protect the community. Meanwhile, four indigenous people and a wise man decide to carry out one of their usual surveillance tours of their sacred sites. They get ready to go to Hamaca Hill.

Read story in Spanish on Agenda Propia.