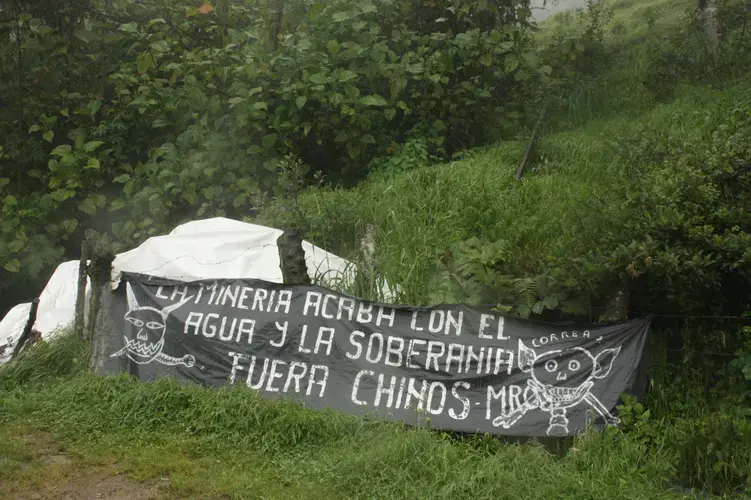

Ecuador is banking on the extractives sector to power its development but Río Blanco, one of the country’s biggest mining projects, is caught up in a legal battle that will be decided in the constitutional court.

Judges from Ecuador’s highest court will determine how to end three years of legal and even physical confrontations between Chinese mining company Junefield Ecuagoldmining and several local communities in the mountainous southern region 60 kilometres from Cuenca City.

In a first hearing, residents defeated the company, which wants to exploit the Río Blanco mine’s gold and silver deposits. However, President Lenín Moreno’s government appealed the ruling and the case remains in limbo.

Pending a final ruling, the highly publicised case has exposed the difficulties faced by Ecuador’s mining sector: the lack of dialogue between companies and communities; concerns about its environmental footprint; and the near complete absence of the state.

Gold and Water

There are only two routes to Río Blanco, a hamlet shrouded in fog around 3,550 metres above sea level. Both have metal barriers that block the way. Each has a different operator.

Communities opposing the gold mine have blocked the paved roadway to prevent Junefield’s vehicles passing. A private surveillance company hired by Junefield controls the passage through the stony secondary road that hugs the rocky mountainside. It has the approval of the National Police.

The two roadblocks provide physical evidence of a divisive and escalating social conflict in a sparsely populated area that’s rich in gold and water.

“We cannot enter our territory freely. We are under their control. On many occasions, we are asked for documents. We built this road without assistance because the company didn’t want to help,” says peasant leader Elizabeth Durazno, who wears a purple wool hat to protect against the chill of the high Andes.

The 37-year-old mother of four is one of the most recognisable faces in Río Blanco, where she is known alternately as ‘The Resistance’, ‘The Fighter’ and ‘The Preventer’.

The road barriers are just one cause of confrontation between several dozen indigenous farmers and the company, part of the Chinese private conglomerate Junefield Mineral Resources Holdings. The gold and silver deposits they control are valued at over US$200 million.

Junefield inherited the conflict when it bought the mine from the Canadian International Minerals Corporation (IMC) in 2013. But it has since mushroomed.

Most of Río Blanco’s residents have worked for the mining company. They accuse it of not fulfilling its commitment to providing long-term jobs; failing to improve the local quality of life; choking a lagoon with debris; promoting divisions within the communities; and above all, not consulting them on the project’s impacts.

True or not, neighbouring villages are split over the project. Most of the 80 Río Blanco families oppose the nearby mine whereas they approve in Cochapamba, which is further from the mine but within its direct area of influence. Further down the access road, residents of Yumate unanimously decided to block access to the mine’s vehicles, while the town of Molleturo, where the local government sits, is more favourable.

There are confrontations within the communities too. Junefield’s detractors attribute this to the mining company. Its supporters blame those who oppose it.

All this has contributed to an escalation of the conflict with no clear path towards a resolution.

Tension peaked in May 2018, when an initially peaceful protest in Río Blanco ended with the mining camp ablaze. It’s unclear exactly what happened. The Chinese company says peasant farmers started the fire, who in turn blame the mine’s private security contractors.

As well as the fire, there are disputes over water.

The Río Blanco mine is located at the edge of the Cajas National Park, which contains hundreds of high altitude lagoons. They feed a dozen rivers that carry water to the town of Cuenca and to the Ecuadorian coast. They also feed into the Amazon basin.

Communities fear mining activities could affect the National Park’s water, which would be prohibited by law. The company insists the project lies 3.5 kilometres outside the park’s perimeter and that it would have no impact on water quality.

“To eat, we have to take food from Mother Earth. We live off the fields and irrigation, so what’s going to happen? We don’t want that to be lost. The Chinese company will not listen to us,” says farmer Beatriz Loja from Yumate, an hour northeast of the park. Her streams descend from the Río Blanco.

Water from Cajas’, considered a UN Biosphere Reserve, is so highly prized that the case became politically sensitive in Cuenca, Ecuador’s third city, which depends on supplies and whose courts have provided an arena for the dispute over this past year.

Río Blanco’s Legal Battle

While most media have focused on the tense relationship between communities and businesses in Río Blanco, the case has been advancing through the courts.

On June 1 2018, Judge Paúl Serrano ordered the suspension of activities at the mine and the demilitarisation of the area. He was responding to a legal protection action filed by the communities. They argued that they had lost their right to water and work and their right to prior consultation had been violated.

The Ecuadorean government appealed that decision and the case was brought to the higher Azuay Provincial Court. On August 3, amidst great expectation and noisy crowds lining Cuenca’s Calderón Park outside the court, three magistrates ratified the ruling.

The communities’ dual victory hints at a successful new strategy in Ecuador and elsewhere in Latin American. However, the win is still not final because the Ecuadorean government appealed and escalated the case to the constitutional court, the country’s top judicial authority.

Aware that protests and roadblocks often end in confrontations with security forces and even in criminal proceedings against their leaders, local communities are focusing on legal and political avenues.

In April this year, the Waorani indigenous people of the Ecuadorean Amazon won a similar case over an oil project in their territory where there was no consultation. Last October, another court ordered protections for the Cofán Indians of Sinangoe, who filed an identical complaint against several mining concessions.

Río Blanco was the first of those victories. Countless indigenous organisations and legal NGOs lent their support, intervening in judicial hearings that addressed residents’ concerns.

Among the lawyers was Zhang Jingjing, a prestigious Chinese environmental lawyer who has brought a number of public interest cases in China. Zhang emphasised China’s commitment to ensure that its companies respect environmental standards and ethnic minorities’ rights in countries where they operate.

“It is time for Chinese companies that invest, or which will be investing in Latin America to face the challenge, learn from good global practices, listen sincerely and respond to the calls from affected communities,” Zhang, who runs the University of Maryland’s Transnational Environmental Accountability (TEA) programme, wrote in Diálogo Chino.

However, there is a significant difference between the Río Blanco case – the crux of today’s dispute – and other legal victories.

Fighting for Identity

Río Blanco’s inhabitants only identified themselves as indigenous Cañari Kichwa in 2017, when the Junefield conflict was already underway. They drafted statutes and registered with Ecuarunari, national indigenous organisation’s arm that brings together indigenous peoples of the Andes.

As indigenous people, they would have the right to demand free and informed prior consultation on the project under the Ecuadorean constitution and the International Labour Organisation’s convention 169, which Ecuador has ratified.

However, the issue of self-identification is thorny. President Lenín Moreno’s government disputes that the Río Blanco community is indigenous, arguing that such details were not available when the mine became operational.

Ironically, following the 2010 census, it was the Ecuadorean government itself – then led by Rafael Correa, with Moreno as Vice-president – who encouraged communities with indigenous roots to declare them.

“Until now, the Ministry of Mines has said that we are not indigenous peoples, but rather mestizos. We identify ourselves as indigenous,” says Durazno, pointing out that they meet two of the necessary criteria: they have surnames demonstrating indigenous ancestry and historical documents proving that the parish of Molleturo was home to the Cañari-Kichwa people.

“Indigenous peoples have been victims of many violations of their collective rights, despite the fact that prior consultation is in the constitution,” says Lauro Sigcha, leader of Azuay’s Federation of Indigenous and Peasant Organisations (FOA), which helped residents of Río Blanco to organise.

“The government of Rafael Correa, who certified who was indigenous and who wasn’t, reinforced the idea that we oppose development and technology, that we want to live like our ancestors, and that we’re the ones lagging behind. He delegitimised us, especially the leaders,” Sigcha adds.

The political struggle in Ecuador over who counts as indigenous (and who doesn’t) rages on. With scant options for local communities to participate in decision-making over mining, oil and other projects that affect their territory, many seek to qualify.

The constitutional court will no doubt examine this given that the Moreno government filed an extraordinary protective action against the last ruling. Due process was not followed, it argued, and requested permission for the company to resume operations. A substantive decision could be a year off since the Court has over 8,000 cases pending.

This should clarify a situation that confuses everyone.

“We still don’t understand the implications of the suspension,” says Andrés Durazno, secretary of the Río Blanco Agro-Ecology Association, who also opposes the mine.

Anti-Mining Lawyer to Provincial Governor

Carlos Yaku Pérez is the lawyer at the forefront of the inhabitants’ strategy against the gold mine.

With a ponytail and a rainbow handkerchief knotted around his neck, the 50-year old Pérez is a charismatic figure. Until recently, he led regional indigenous organisation Ecuarunari. He advised the Río Blanco community to identify as Kichwa Cañari and instituted a protection action on their behalf.

Though known in Cuenca after years litigating water and indigenous rights cases, the legal victory over Junefield further cemented his notoriety.

“Of course we are indigenous. Our surnames, our colour, our worldview is,” Pérez says. “But here [in Ecuador] there is a very general modus operandi. There is no prior consultation. They confuse the issue of prior consultation with socialisation, with hearings, with anything else that it’s not,” he adds.

Pérez posits that the legal victory would have been impossible under Rafael Correa’s government, which exerted strong pressure on the judicial branch.

During the legal process, Pérez complained that he was illegally detained by residents who supported the mine. He says he received death threats and was beaten. Following the episode, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), an arm of the Organization of American States (OAS), granted him injunctive relief, requesting that Ecuador guarantee his security.

In another twist, this year Pérez decided to run for prefect of Azuay province as a candidate for the Pachakutik Indigenous Party. He campaigned as a “defender of water” and played the saxophone in the streets.

His victory in March elections was as surprising as it was emphatic. He won with 117,000 votes, over 10 percentage points ahead of his nearest rival.

Pérez’s career reflects the increased influence of the indigenous cause in Ecuador over the past two decades.

He was a founder and the first President of the provincial Federation of Peasant and Indigenous Farming Organisations (FOA), led Ecuarunari and become a director of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (Conaie). As Azuay’s Prefect, he became only the third indigenous Prefect of Ecuador.

Two years ago, in the process of self-identifying as Kichwa Cañari, he changed his name from Carlos Ranulfo to Yaku Sacha, meaning, ‘water from the mountain’.

The day Azuay went to the polls, mining was a big issue. Some 86% of inhabitants of three villages in Azuay – including the one where Pérez grew up – voted against mining in a referendum that grew out of another social and environmental conflict. That dispute, over Canadian mining company Iamgold’s Quimsacocha project, was the first that Pérez and the FOA pursued legally.

Pérez’s presence in the regional government will likely make the political environment around mining even more complex. One of his first promises on taking office was to advance a popular consultation – similar to Quimsacocha’s – at the provincial legislature. It aimed for all Azuay’s inhabitants to have a say on mining near water sources.

His campaign not only generated enthusiasm in Río Blanco, evidenced by posters and stickers on houses and farms, but also among urban citizens in Cuenca where water is a sensitive topic.

“Territories are emerging that see the potential in self-identifying as indigenous peoples and see that there are international treaties that support it,” says Sigcha. “They no longer see it as a setback, but as a form of protection for their territories, especially from extractive projects.”

Ecuador’s Mining Drive

The lawsuit that entangled the Río Blanco mine created a dilemma for President Moreno, who considers it one of four “strategic” mining projects.

“When you have a project that can easily produce 610,000 ounces of gold, as well as 4.3 million ounces of silver, at current prices of US$1,325.60 per ounce, it can give you a sense of how important this project could be from an economic point of view,” deputy mining minister Fernando Benalcázar told Diálogo Chino at his Quito office.

“Before the shedding process in October, they had 656 people working there, plus the taxes they paid… Bottom line: it has a huge impact for all of us in a country that basically needs this type of investment,” he adds.

Ecuador depends on Junefield, a Hong Kong-based company which also has gold and copper mining projects in Peru, to meet its goal of mining contributing 4% of GDP by 2020. Last year, Moreno established a “super ministry” to drive long-term policy for the hydrocarbons, mining and energy sectors.

“People from Río Blanco are the direct beneficiaries of jobs, capacity building and the provision of services to the company, going from the most basic things like laundry services all the way up to catering services and manpower for the project,” says Benalcázar.

Many residents welcome local investment in the mine, which was inaugurated in 2016 by former Vice-president Jorge Glas, since imprisoned as part of the continent-wide corruption scandal involving Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht.

“As a community, we have demanded only that the government put its house in order. If it has to be done, it must be done well,” says Manuel Muevecela, leader of the Cochapamba community whose family hails from Río Blanco.

“These resources should be put to the benefit of the communities and invested in basic needs, prioritising education, health, roads and productive projects,” he adds. “Of course, there will be impacts, including on the environment, but we must ensure that there are more positives than negatives”.

However, the Ecuadorean government remains focused on perceived agitators.

“Is there a conflict? Yes, among certain people who don’t even belong to this community,” says Benalcázar. “Of the eight leaders, six are from outside the community and they are under the leadership of one person. A minority is trying to compromise a project of national interest,” he adds, without naming Pérez.

The government says the inhabitants of Río Blanco are not indigenous, but peasant farmers.

“In certain specific circumstances, there should be free, prior, informed consent, not from [all] communities…but from ancestral indigenous communities who have been there even before the colonial days and the Spaniards and who are protected by the Ecuadorian constitution,” Benalcázar says.

“Some people, with other interests, manipulated this and are trying to obtain a veto power that in no way is established in our constitution, nor in international conventions to which we have subscribed,” he adds, stressing that the government will respect any final judicial decision.

Pro-mining communities who identify as mestizo broadly agree and attribute to Pérez a personal political agenda and opportunism in ‘playing the indigenous card’. They say they have been the victims of road closures, but distance themselves from it by acknowledging that their opposing residents are genuinely local.

Those in favour of mining fear Río Blanco will become a large illegal operation. Benalcázar cites the dramatic precedent of Buenos Aires in the north of Ecuador, where there is little state presence and criminal gangs oversee the illicit extraction of gold.

“Rio Blanco could be the next target for illegal mining. There is a huge difference with them: modern slavery, prostitution, money laundering, zero taxes or royalties, environmental damage. They don’t give a dime,” Benalcázar warns.

Whether such outcomes are likely, communities are increasingly concerned about environmental damage and are becoming sceptical of the supposed economic benefits. The companies and the government say such fears are based on misinformation or activism and repeat that they use the latest extractive technologies and bring progress.

There is no space for dialogue where communities, companies, and authorities can talk face to face. “They preferred to talk to groups of workers and [asked us] to pass the word to their families. For us, the company’s policy has been not to talk to everyone,” says farmer Rubén Cortés.

Diálogo Chino attempted to contact Junefiled Ecuagoldmining by phone and in person. The company said its local manager was very busy with meetings in Quito and required permission from its Beijing headquarters. “You should talk to the Ministry of Mines. They are our partners,” they said on visiting their office facing Cuenca’s Tomebamba River.

All villagers, whether in favour or opposed to the mine, seem to agree that the government has been totally absent.

“It has not done enough to resolve this. It carried out its management duties to deliver the concession, but the follow-up has been inadequate. It is a total abandonment of state institutions,” says Muevecela.

“The state is a part of this conflict. It has shown that it is incapable of seeing the complexity of the problem, thinking that it’s acting in our best interests, but without even understanding the positions of the communities,” says Ivonne Yánez, a biologist at NGO Acción Ecológica, which has followed the legal process.

They also recognise the need for a broader participatory model that does not only protect ethnic minorities.

As Sigcha says; “This should not only be for indigenous people, but for all those who live in territories whose communities are being threatened. Why is the preference only for indigenous people in these cases?”

The government often only appears when it has to put out a fire and when investments are in jeopardy. Communities get frustrated by decisions made hundreds of kilometres away. Everything is reactive and de-escalation can become almost impossible.

However the constitutional court eventually rules, the path towards de-escalation of the conflict in these misty Andean hamlets remains unclear.

“Even if the president of the country himself comes, we are not interested in talking about mining. We don’t believe him anymore, it’s too late”, says Río Blanco leader Hipólito Pacheco.

Read this story in Spanish here.

Read this story in Portuguese here.

- View this story on GK