It all started with the name, “The Atlantic Conquest.” Who, in the 21st century, would think of such a name for a project to build a road through indigenous territory? Well, the Panamanian government did.

The symbolic violence of the name caught our attention, and we began to investigate. We knew from other similar experiences that opening roads in primary forests brings about two major consequences: massive deforestation and speculation over land ownership. Although the Atlantic Conquest project was marketed as a social aid that would connect even the humblest communities with health facilities and schools, we sensed that there would be winners and losers. The road would open access to paradise-like beaches and mountains whose mineral resources are among the richest in the world.

We then began an investigation that sought to find who—according to public documents— actually owned the land that indigenous people and peasants have inhabited for centuries without formal title deeds. To them, the title deeds were the bodies of their ancestors buried in the ground there.

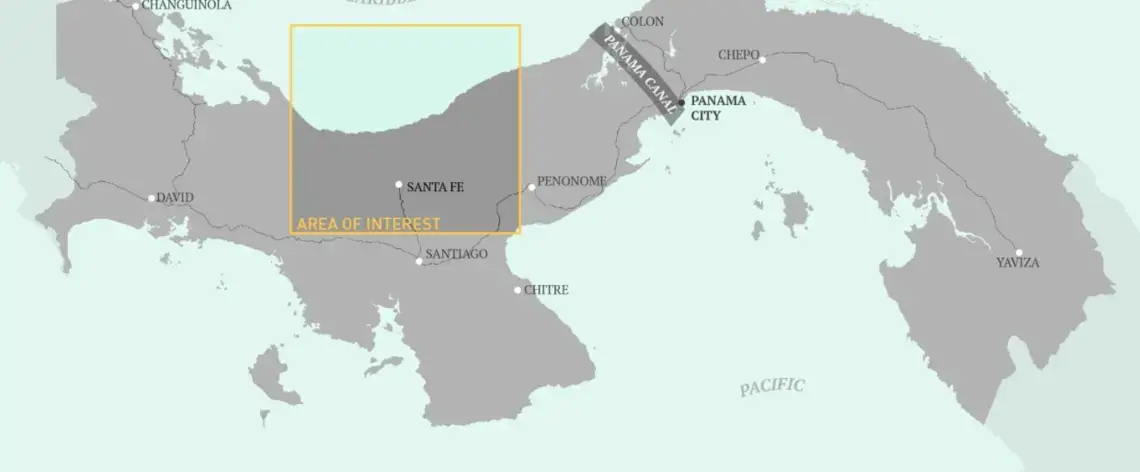

Given the lack of organization, centralization, and digitization of public documents, we were forced to divide the project’s area into five pieces, with one journalist investigating one sub-area. This way, we could cover the entire territory affected by the construction of the road, from the highlands to the seaside.

Shortly after we started, we realized that the strategy was wrong.

We accessed files with the maps on paper, but the names of the owners were meaningless to us: names of societies that led to other societies. Diving into the endless number of companies and foundations in the public registry of Panama was an impossible mission because the system is deliberately designed to conceal the identity of the owners of these firms.

We then decided to do two things: travel to the area to see what people had to say and start looking at the problem from the lens of politicians and businessmen in the area, searching for their names in the registry.

The locals were concerned about the threat to forests and nature, which they consider living space, not business.

The results began to show up rapidly: We found in the archives that Pedro Miguel González, the leader of the opposition and the deputy for Santa Fe—the starting point of the highway—had just titled 49.5 acres for a total of $138, or less than $3 per acre. In Santa Fe, people could not stop talking about the beaches: They said that speculators were titling land massively there. So, there we went.

Getting there was not easy. The trip was by cayuco through a river barely deep enough to navigate. We had to get out every now and then, walking between the stones, pushing the boat until we could eventually continue navigating. It was mid-September—rainy season—and a monumental downpour started. You could not see more than a hundred meters away. Suddenly, the captain of the boat shouted:

“Everybody out! There comes a flash flood!”

Immediately, the river began to turn dark and branches and trunks began to fall downstream. We reached the shore, but the water was rising so fast that it reached chest level in less than five minutes.

“No worries, there are no crocodiles in this area!” said the captain, laughing. But a local who was traveling with us on the boat shouted:

“Right, Captain, but there are poisonous snakes!” and the two began to laugh.

Raphael Salazar, the photographer, was struggling to carry all of his equipment literally half a meter above the water and did not understand what they were laughing at.

After a while the rain stopped and we could continue traveling.

Arriving at Calovébora, we found an unknown paradise—the best-kept secret of the Caribbean. A small town at the mouth of the river, surrounded by endless white-sand beaches and primary forest, turquoise water, and dozens of pelicans and seagulls turning around. We understood why Calovébora would be targeted by speculators.

It did not take long before we learned of the existence of Max van Rijswijk, an alleged Dutch businessman about whom everyone spoke. Several peasants accused him of fraud by titling their own land without paying them what was promised. These people could not even read or write and had spent their entire lives in the mountains. They even accused him of threats and violence.

Once back in the city, we only had to google his name to find his company’s portfolio: Caribbean Riviera. Things were worse than we had first imagined. The Dutch businessman claimed to hold more than 5,000 titled acres, including about 10 miles of coastline. There were lots for sale at 14 million dollars. The portfolio included slogans such as "Don't wait to buy land: Buy land and wait." It was an endorsement of speculation.

We went back to rooting through documentary research, but this time with a more specific objective. We found dozens of companies and foundations belonging to the Dutch businessman, his frontmen, and his lawyers. We found transfers of illegal companies as well as fraudulent titles, and we confirmed that he had titled lands that people claimed they had not sold. Even so, we had the feeling that there was something more behind all this. Once again, the facts showed us the way. It was all about watching the news.

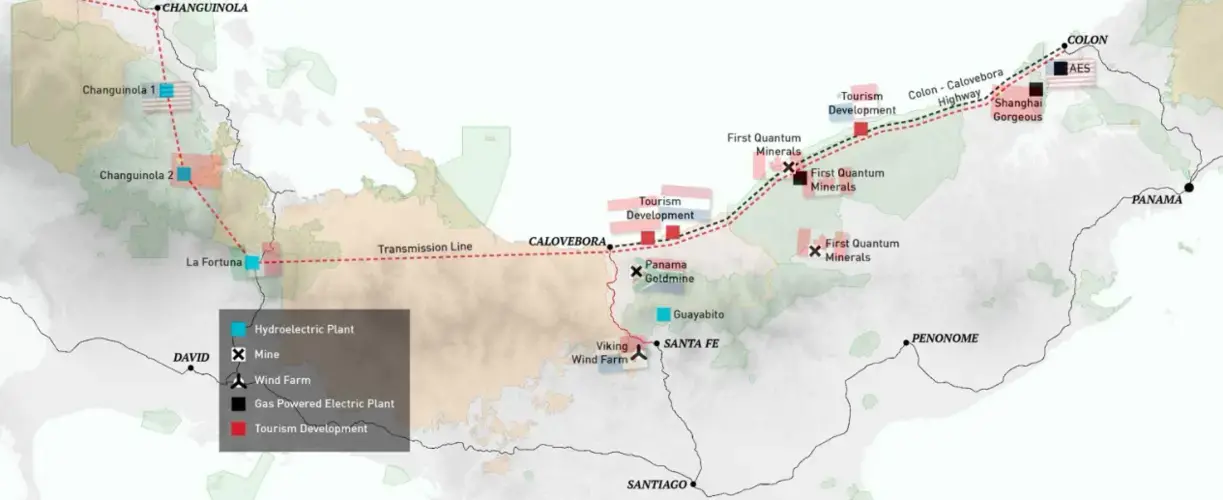

In September 2017, the National Assembly had decided to remove the protected status of a coastal area near the highway to allow for tourism developments.

That same month the President of the Republic, Juan Carlos Varela, praised mega-mining while visiting the Minera Panama mine—the second largest copper mine under construction in the world—owned by the Canadian company First Quantum. In October, the government announced the creation of a state-owned mining company. We understood that the road was, in fact, only the first step of a much larger project: the Atlantic Conquest.

We confirmed this when we got access to the permits for mining and hydroelectric exploitation, as well as plans for a new transmission line that would connect Panama with Central America and Colombia. In other words, it is a way to take extractivism to its final form—the transnationalization of natural resources. Meanwhile, local communities hopelessly watch this process of transformation that will surely bring consequences to their way of life.

We learned that revolutions in journalism are always about the same thing: telling a story well.

However, the evolution of data analysis and visualization tools has helped us not only enhance the narrative experience, but also understand a story’s contents with more precision.

It was not until we started working on the maps that we really understood how the Atlantic Conquest is nothing more than a story about the transnationalization of natural resources.

As we developed the maps, more and more data was required. The maps themselves were pushing us to deepen our investigation, searching for new layers of information. We could even say that the whole story unfolds just looking at the maps.

Once we had the necessary information—and even much more than we needed—we sat down to outline the kind of narrative we wanted to develop.

The result of the investigation is available here.