In late 2018, ethnic Rawang in Kachin State’s northern Hkakabo Razi region turned against the Forest Department and its international partner, the Wildlife Conservation Society, and drove them out following a series of protests and the torching of a Forest Department guard post.

“The communities don’t let anyone in; their minds are so wounded,” said Ko Phong Phong, a Rawang youth from Khar Lam village, in the foothills of Hponkan Razi, a mountain in Putao Township.

The expulsion of the two groups marked the culmination of rising tensions over a plan to nominate 11,280 square kilometres known as the Hkakabo Razi Landscape – named after its dominant feature, Hkakabo Razi, Southeast Asia’s tallest peak – as a UNESCO World Heritage Site based on the area’s natural significance.

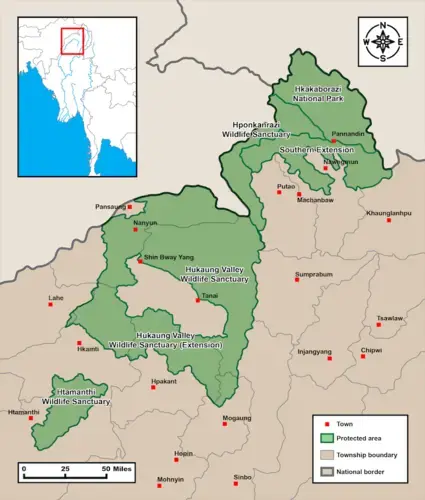

The “landscape” includes the 3,810 sq km Hkakabo Razi National Park in Nawngmun Township, designated a conservation area in 1998, the 2,700 sq km Hponkan Razi Wildlife Sanctuary in Putao and Machanbaw Townships, designated in 2003, and a proposed 4,778 sq km “southern extension” to Hkakabo Razi National Park that encompasses parts of Putao, Nawngmun and Machanbaw townships.

These heavily forested areas host a scattering of remote villages, whose residents must walk for several days to purchase even basic supplies. The areas also possess a rich store of biodiversity, including endangered flora and fauna.

A closer look at what led to the dramatic eviction of forestry officials and a major international conservation NGO – and the derailing of a World Heritage bid – reveals a complex battle of interests spanning international conservation, commercial exploitation, party politics and local desires to wrest back forest management.

A shadow over WCS

The New York-based Wildlife Conservation Society has partnered with Myanmar’s Forest Department since 1993. According to the organisation’s website, this made it the first international outfit to initiate long-term conservation efforts in Myanmar, at a time when most non-profits steered clear of the military junta.

The WCS presence in northern Kachin goes back to 1996, when the organisation’s former director of science and exploration, Dr Alan Rabinowitz, joined the Forest Department’s Dr Thein Aung on expeditions to remote villages in the foothills of Hkakabo Razi.

Rabinowitz, a famous American zoologist and big cat specialist, was described in a 2008 Time magazine article – called “The Indiana Jones of Wildlife Protection” – as “unapologetic about his work with the junta”. This was in relation to his efforts to establish the world’s largest tiger reserve in Kachin’s Hukaung Valley, which was designated in 2004. Just two years later, the military regime awarded concessions for biofuel production inside the reserve to Yuzana Company, known to have ties to Senior-General Than Shwe, the Tatmadaw chief who ruled Myanmar until 2011. Well-documented complaints of land grabbing and the forced displacement of communities followed soon after.

Prior to arriving in Hukaung, Rabinowitz was already making headway in Kachin’s northern forests, where following two years of expeditions he supported the Forest Department in gazetting Hkakabo Razi National Park in 1998.

The conversations that went on between Rabinowitz and local Rawang villagers during those two years still cast a shadow over WCS.

Rabinowitz, who died in 2018 after a long battle with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, wrote in an article titled “The Price of Salt”, published in 2000 in the American magazine Natural History, that villagers’ need for basic goods, and especially salt, led them to kill and trade rare and endangered wildlife. “The villagers knew their hunting was not sustainable … yet they readily exchanged these dwindling [wildlife] resources for clothing, tea, and – above all – salt,” he wrote.

To convince the government to designate the area a national park, he wrote, “I presented officials with a plan – suggested in part by the villagers themselves. They had agreed to limit their hunting and to monitor the population trends of key game species in exchange for regular shipments of good quality salt and other necessities to be supplied by the park staff … With the incentive of being provided with basic necessities, people would presumably no longer kill animals other than those intended for their own consumption, and the wildlife trade would therefore be curtailed.”

A postscript notes that in early 2000, Rabinowitz and the Forest Department’s Thein Aung returned “to talk with local villagers about the park and to bring basic necessities – salt included – in exchange for protecting wildlife.”

Some Rawang today allege that these promises extended further. Hpong Ri Minn, a former member of both the Rawang Literature and Culture Association and the Putao chapter of the Union Solidarity and Development Party, told Frontier that WCS did a survey, in which it asked how much each family spends per year. WCS “said they would build warehouses and store salt, rice, oil and basic items” to compensate for livelihood restrictions, he said. “The communities accepted [the park designation] if the organisation could support them.”

Park regulations banned commercial hunting, logging and the commercial trade in wildlife, wild plants and other forest products, such as bamboo, rattan, mushrooms and honey, as well as shifting cultivation. The Forest Department set up four guard posts in the park to monitor for illegal activities.

Thein Aung, who served as the park’s warden from 1999 to 2007 and is now retired, told Frontier that small-scale subsistence activities were allowed through a verbal agreement with communities.

However, Rawang interviewed by Frontier allege that coming under Forest Department management disrupted their livelihoods and made it difficult for them to survive.

For example, Hpong Ri Minn blamed the Forest Department for effectively preventing children from finishing school. He said that after Forest Department guards began confiscating wildlife horns and skins that young people would sell in town to help pay for their education, many students dropped out of school.

“After decades, the community was devastated and they felt ill will,” he said, adding that the situation had resulted in many families moving out of the park, to the towns of Putao, Nawngmun and Machanbaw.

Outstanding universal value

In 2013, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization commissioned a study of potential natural world heritage sites in Myanmar on behalf of the Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry (known as the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation since 2016). The list included the “Hkakabo Razi Landscape”, encompassing Hkakabo Razi National Park and Hponkan Razi Wildlife Sanctuary.

Hponkan Razi, which stands at 5,165 metres, and its neighbour to the northeast, Hkakabo Razi, at 5,881 metres, are Southeast Asia’s tallest peaks. The area also contains vast biodiversity, including the globally-threatened black musk deer, red panda and white-bellied heron, as well as 106 species of orchids.

Although becoming a world heritage site has no specific legal implications, if the environment within a site becomes threatened, the World Heritage Committee, a body made up of member states, may put the site on an endangered list or rescind its world heritage listing. This international censure and pressure can sometimes help to protect an area, said Ms Min Jeong Kim, who has been UNESCO Myanmar’s head of office since early 2017. In an interview with Frontier on February 24, Kim said the World Heritage Convention guidelines are meant to be implemented using national legislation – in the case of Myanmar, the 2018 Conservation of Biodiversity and Protected Areas Law and the Forest Law of the same year.

After a series of workshops involving UNESCO, conservation groups and the Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry it was decided to add a “southern extension” to Hkakabo Razi National Park, to strengthen its claim to outstanding universal value, which is the defining factor in a world heritage designation. The extension would more clearly distinguish the area ecologically from the Three Parallel Rivers in the neighbouring Chinese province of Yunnan, which was inscribed as a World Heritage site in 2003.

The ministry submitted a tentative list of nominations, including the Hkakabo Razi Landscape, to UNESCO in February 2014.

In 2015, with funding from the Norwegian government, UNESCO sub-contracted WCS to provide support to the ministry with parts of the nomination process. Kim told Frontier that WCS was a “natural partner” for the UN agency and said she was not aware of any controversy surrounding the organisation.

“WCS had the greatest capacity to reach out to local communities and work with the Forest Department as the organisation was already present and active at the site,” she said. “I think that was the main consideration that was taken into account.”

In late 2016, UNESCO made a series of visits to the region to meet stakeholders, including representatives of the Kachin State government and the Rawang Literature and Culture Association. “The people we met were quite receptive. It seemed clear they wanted a World Heritage nomination,” said Kim. “They thought it would be good to put Hkakabo Razi on the global map, and bring pressure to those trying to exploit the area for their own means. They mentioned there were a lot of different vested interests in the area,” including traders in flora and fauna and those enaged in timber and mining, she said.

But when the Forest Department and WCS started visiting communities in the proposed Southern Extension at about the same time, public opinion appeared to be shifting.

“They [WCS and the Forest Department] explained that the Hkakabo Razi area wasn’t enough; it needed to be extended to meet UNESCO’s requirements,” said Hpong Ri Minn. “Many of those in the extension area didn’t agree. They wondered if they would have to move if the area was extended. They couldn’t accept it.”

Perceptions that WCS had not fulfilled promises made since 1996, combined with frustrations built up over the years among Rawang towards Forest Department management in existing park areas, seem to have hardened attitudes against the Forest Department and WCS, contributing to opposition to the world heritage nomination, according to four local Rawang interviewed by Frontier.

“Locals said they wouldn’t allow the southern extension of Hkakabo Razi [National Park] because WCS didn’t keep their promises from before,” a local Rawang, who requested anonymity, told Frontier.

In the first half of 2017 the Rawang Literature and Culture Association wrote twice to the union government to say it opposed the Southern Extension but received no reply, according to The Irrawaddy, which reported that on July 28, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation then unveiled plans to proceed with the nomination. Frontier was not able to independently verify this information.

Two months later, on September 28, demonstrations were held in the towns of Putao, Nawng Mun and Machanbaw and the village of Ma Khum Kan against the world heritage nomination, the southern extension of Hkakabo Razi National Park and the presence of WCS in park areas.

In October 2018, residents expelled a joint WCS-Forest Department field monitoring team from Hponkan Razi Wildlife Sanctuary. A month later, locals burned down one of the Forest Department’s guard posts, at Da Zun Dam village in Hkakabo Razi National Park.

Since late 2018, communities inside the wildlife sanctuary and national park have blocked entry to outsiders, including WCS and Forest Department personnel. The World Heritage nomination has been suspended indefinitely.

“The Rawang understand the Putao region including Hkakabo Razi as their land. They want to manage their land, and they do not want it to be managed by the central government,” said Thein Aung of the Forest Department.

UNESCO Myanmar head Kim said mysteries remain about the community’s opposition to the nomination.

“We never understood where the information gap was happening with the community’s perception and understanding of UNESCO. Misinformation around UNESCO’s role persisted for a long time, and probably never went away,” she told Frontier.

Phong Phong, who participated in the demonstrations, gave a more direct explanation. “It happened like that because [WCS] didn’t do as they had promised,” he said. “Without solving the existing problems, they proposed the UNESCO [world heritage site]. It became unacceptable to the people.”

“They abused our trust,” he added.

“They neglected the community and didn’t help with anything,” said Ko Sanlu Ram Seng, a mountain climbing guide from Da Hun Dam, a northern village in the Hkakabo Razi region. “The villagers said, from today, we won’t accept you anymore because nothing happened as you promised."

'They know the public’s desire’

Villages inside the “Hkakaborazi Landscape” are populated mainly by the Rawang, with smaller numbers of Lisu and Tibetans. The residents of the surrounding area, including Putao town, the hub of northern Kachin, include Lisu, Rawang, Jinghpaw and Hkamti Shan, also known as Tai Khamti.

Political rivalries and business interests complicate any analysis of the controversy. Several sources who spoke to Frontier about how these interests might have influenced the dispute over the World Heritage nomination did so on condition of anonymity.

The 2017 demonstrations were led by the Rawang Literature and Culture Association and supported by the Jinghpaw Culture and Literature Association. The Lisu Culture and Literature Association did not participate and neither did Tibetans or Hkamti Shan.

The Rawang Literature and Culture Association chairperson Marip Yaw Shu declined Frontier’s request for an interview.

Culture and literature associations have existed in the form of committees since before the transition to semi-civilian rule in 2011, according to Hpong Ri Minn, who served on the Rawang Literature and Culture Association from 1999 to 2016. Today, the associations are able to register with the Ministry of Ethnic Affairs, from which they may request funding for activities aimed at preserving ethnic traditions.

Hpong Ri Minn said the Rawang Literature and Culture Association, which was established in 1994 in Khaunglanphu and is today headquartered in Putao, is apolitical by mandate, but “on things related to the [Rawang] nation, the committee meet and give advice on behalf of the people.”

Ram Seng of Da Hun Dam village said the public requested the Rawang Literature and Culture Association to lead the 2017 protests “because they know the public’s desire and what we want”.

Phong Phong shared a similar view. The association “represents all the Rawang people and all the villagers in the mountains”, he said, adding that its leaders “are regarded as parents of the people in this area”.

But others say party politics played a role in opposition to the World Heritage nomination.

All three members of parliament in Nawngmun Township belong to the USDP, making the area in and around Hakabo Razi National Park a rare stronghold for the Tatmadaw-aligned opposition party.

Hpong Ri Minn said that the nomination was opposed by USDP supporters, while those who supported it were more likely to favour the ruling National League for Democracy party. “The [USDP] couldn’t accept [the nomination] because the party knows the difficulties the public are facing,” he said.

A Rawang community member familiar with the nomination controversy, who spoke on condition of anonymity, told Frontier, “What the NLD did, the USDP didn’t like … The villagers were taken advantage of.”

Beyond party competition, a murky array of commercial interests the stakes of nature conservation.

A description of the proposed Hkakabo Razi Landscape on the UNESCO website written in 2014 noted that logging, mining, commercial wildlife hunting and the gathering of non-timber forest products posed environmental threats in the area.

One conglomerate with ties to the Tatmadaw and a presence in northern Kachin is the Htoo Group of Companies, whose chairman and founder U Tay Za has been a close associate of the former junta chief Than Shwe. Htoo Group runs Malikha Lodge, a luxury hotel in Putao, and operates throughout Myanmar with subsidiaries involved in logging and timber exports, as well as construction, manufacturing, transport and logistics, according to its website. Frontier did not explore the extent to which these activities were being pursued in Kachin.

A Chinese company, the Inner Mongolia Duojin Investment Co Ltd, expressed interest in mining parts of Machanbaw, Nawngmung and Putao townships in 2019. In March 2019, the Kachin State government rejected the company’s proposal to conduct a feasibility study to mine for gold and other minerals over nearly 500,000 acres (about 2,020 sq km), citing environmental concerns. The area overlaps with the stalled world heritage nomination area, according to Kachin News Group.

Natural resource interests in Khaunglanphu township, which lies just south of Naungmun township and is also a heavily forested area, have also been the subject of controversy recently. The Irrawaddy reported that the company Fortuna Metals submitted a proposal to the Kachin State government in August 2018 – approved in November 2019 – to conduct a feasibility study for the extraction of gold, metals and other minerals over nearly 300,000 acres of the township. Two of the company’s directors are Australian and one is a Myanmar national, according to the DICA website. On May 20, Amyotha Hluttaw lawmaker J Yaw Wu told parliament that local communities oppose the project because they risk losing farmland and community forests.

Another company with a seemingly long presence in Khaunglanphu Township is the La Pyi Wun Gold Mining Company, which locals told Frontier has won a tender from the government for road construction. One of six directors listed for the company on the website of the Directorate of Investment and Company Administration is Ray Dam Tang. Also know by the names Ah Dang and Tanggu Dang, Ray Dam Tang, who is Rawang, made a failed run in 2010 for Putao’s USDP seat in the Pyithu Hluttaw. He is better known as the founder and current head of the Rebellion Resistance Force, or Ta Ka Sa Pha, also known as the Rawang militia. The militia it is one of several Tatmadaw-supported “people’s militias” across the country.

The RRF was founded in 2006 with support from then Tatmadaw Northern Regional Commander Maj Gen Ohn Myint. It began out of a splinter group of the New Democratic Army-Kachin – an armed group run by the prominent warlord and former parliamentarian Zahkung Ting Ying, which formed as a splinter of the KIO in 1989 and is now a Border Guard Force under Tatmadaw command.

A 2009 report by London-based campaign group Global Witness described Ray Dam Tang as a businessman involved in Kachin’s jade industry. It said through the La Pyi Wun company he was also building roads in Khaunglanphu Township, which would likely be used to facilitate the extraction of minerals and timber. Kachin News Group reported in 2009 that the junta had permitted the RRF and a Chinese company to dig for gold and other minerals in Khaunglanphu.

Frontier did not explore whether the militia’s commercial interests extend to the Hkakabo Razi area.

‘It won’t be easy anymore’

Anthropologist Mr Laur Kiik, who studies Kachin society and nature conservation, told Frontier that “these Himalayan foothills are places of vast ancient forests, many unique and endangered plants and animals, tragic poverty, big-business interests, decades-long military repression, diverse peoples, and rising inter-ethnic tensions.” The Hkakabo Razi national park controversy is part of a “wider, many-sided rivalry over who will shape these lands’ future, and how”, he said.

With outside conservation groups currently not allowed to visit the area, Rawang are today serving as gatekeepers of the Hkakabo Razi landscape and its resources. Kim of UNESCO Myanmar expressed hope that “local communities who call the area their habitat and whose traditional knowledge has helped to conserve and protect the area sustainably will now take it upon themselves to mobilise to protect the area”.

Ram Seng from Da Hun Dam village hoped a common understanding between Rawang communities and conservation groups could be reached in the interest of keeping out commercial threats. “The best solution is to allow the community to manage [the forest] as they used to do with technical support from organisations,” he said. “I don’t want companies to come in and destroy nature.”

Min Seng, head of the Nam Shani Social Development Organisation in Putao, said communities, the government and local civil society organisations are already discussing how to manage forest resources sustainably.

However, Hpong Ri Minn said the challenges of battling commercial exploitation should not be underestimated. “Now, wood, bamboo and animals have value, and [resources have] become difficult to control,” he said.

Min Seng said he feared that, despite the current initiatives, villagers would not be able to keep out large extractive interests in the long run. “Prioritising villagers’ roles is something the majority want,” he said, “but it won’t be easy anymore.” – Additional reporting by Hkaw Myaw