Abayomi Isinleye, chairman of the farmers’ association at the Oluwa forest reserve, put the losses incurred from the destruction of the cocoa plantations at N500 million ($560,538) or more.

“Just one cocoa tree is generational wealth. You keep profiting from it until you age and hand it to your children. On a plot of land, you can harvest two thousand cocoa seeds annually. Right now, SAO Agro-Allied Services Limited has graded up to 2,000 hectares of cocoa farms,” Isinleye told TheCable.

“In a year, one can make up to N10 million ($11,210) from a cocoa farm, sometimes N20 million ($22,421), depending on how big your farm is. At the moment, cocoa is N3,800 ($4.3) per kilo. A ton is N3.8 million ($4,260). Some harvest six, eight, or ten tons annually. Aside from that, we have other produce on the farm, like yam, kolanut, cassava, and vegetables that we sell to people. So, when a farm is destroyed, the loss is unquantifiable. It is the major source of wealth for many farmers in the state.”

Nigeria is the fourth-largest producer of cocoa in the world, according to the Nigerian Export Promotion Council (NEPC), making the country a leading player in the global cocoa industry. Data on the NEPC website shows that the major destinations for the country’s cocoa are the Netherlands, Germany, Belgium, Malaysia, and the United States, where it is used to produce chocolate.

According to the Ondo State Development and Investment Promotion Agency (ONDIPA), the state is the largest cocoa producer in Nigeria, and it is responsible for over 40% of all cocoa exports in the country. The agency noted that the current cocoa production volume in the state stands at 240,000 metric tons per annum.

The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) report also shows that cocoa-related exports in 2023 totaled N230 billion (about $258 million), which makes the cash crop the highest-earning agricultural export in Nigeria. This emphasizes the significant role cocoa exportation plays in the country’s foreign exchange earnings.

The 2023 third-quarter report of the NBS stated that the export of agricultural products was dominated by superior-quality cocoa beans valued at N42.2 billion ($47 million), which were exported to Indonesia and the Netherlands.

On the other hand, the first and second quarter reports of the NBS show palm oil was only imported into Nigeria from Malaysia, Indonesia, and Cameroon. In the first six months of 2023, Nigeria imported crude palm oil worth N27.8 billion ($31 million) from Malaysia. From 2017 to 2022, Nigeria imported N300 billion ($336 million) worth of palm oil, making it one of the top five imported agricultural products into the country.

In summary, while Nigeria earns a lot of money from cocoa exportation, it spends a lot more to import palm oil.

COCOA VS PALM OIL: CONFLICT IN A RESERVED FOREST

According to a PwC report, in the early 1960s, Nigeria was the world’s largest palm oil producer, with a global market share of 43%. But today, it is the 5th largest producer, behind Colombia, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia, with less than 2% of the total global market production of 74.08 million MT.

“In 1966, Malaysia and Indonesia surpassed Nigeria as the world’s largest palm oil producers. Nigeria is the largest consumer of palm oil in Africa, with a population of over 197 million people. To meet the supply gap for palm oil, the country had to depend on importation over the years. From being one of the leading exporters of crude palm oil in the 1960s, Nigeria is now a net importer,” the PwC report stated.

“According to the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), if Nigeria had maintained its market dominance in the palm oil industry, the country would have been earning approximately $20 billion annually from the cultivation and processing of palm oil as of today.”

As things stand, both cocoa and palm oil are key to the agricultural policy of the government in terms of foreign exchange earnings and meeting local market needs. But the question begging for answers is: Why is there an onslaught on cocoa plantations for industrial palm oil cultivation when smallholder farmers and big investors can plant separately on the land?

Akin Olotu, the senior special assistant on agriculture to the Ondo governor, provided the answer as to why the cocoa farmers were asked to leave the forest reserve for SAO Agro-Allied Services Limited to grade and plant palm trees in line with the CBN initiative.

“They have done incalculable damage to the cocoa business in Ondo state. In the global market, it has been observed that cocoa in Ondo state is planted in the forest reserve, and the EU is of the opinion that they don’t want any chocolate product that is coming from forest reserves. Those that will bear the brunt are the real cocoa farmers that are farming on community land,” Olotu told journalists.

But the government is issuing licences to investors to plant palm trees on the same forest reserve, Tope Temokun, the farmers’ legal counsel, queried. The lawyer said if the government was sincere with the Central Bank scheme, it would revive the abandoned palm tree plantations and palm oil processing companies across the state to redeem its lost glory as the number one producer of palm oil in the world—instead of promoting industrial cultivation in a forest reserve.

A DEPLETING FOREST RESERVE

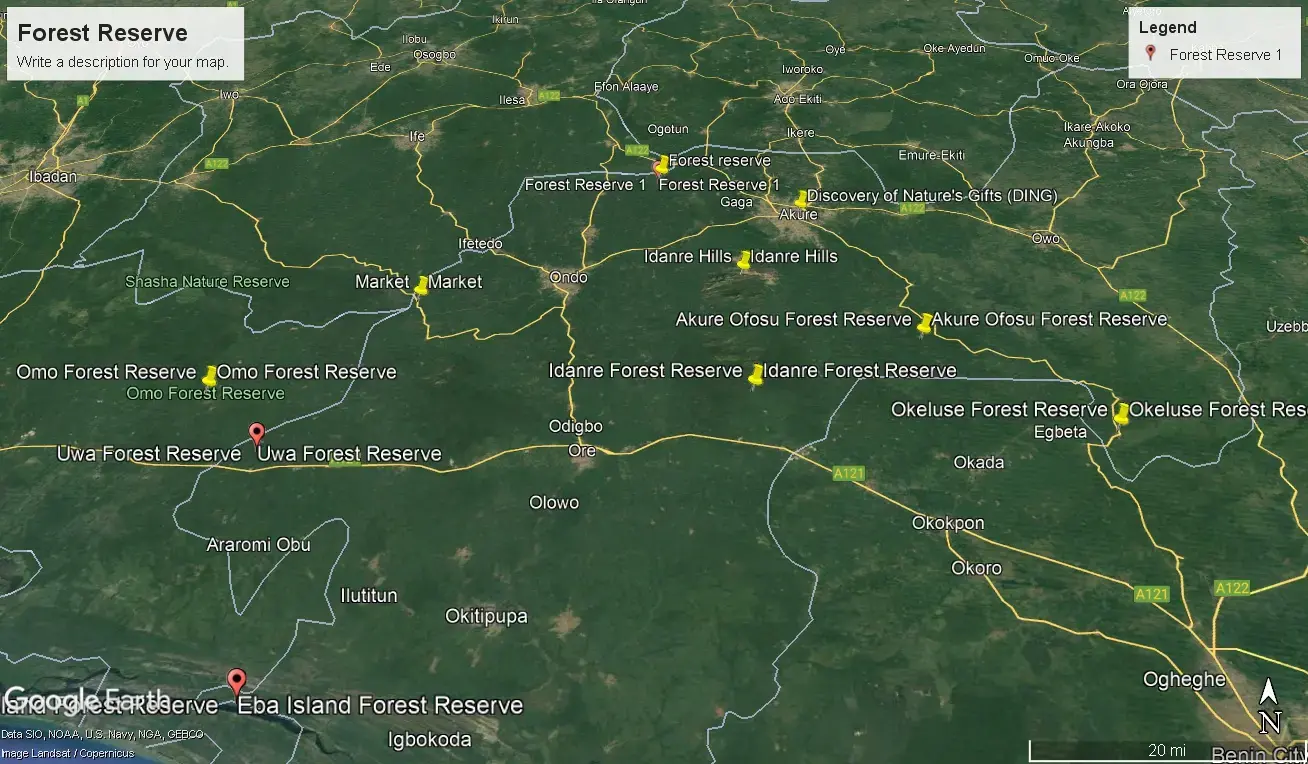

Ondo is said to be the richest state in forest resources in southwest Nigeria. When the state was created in 1976, it had sixteen forest reserves of about 308,000 hectares. Presently, they have depleted to about 250,000 hectares, as some have been completely encroached on. The Oluwa forest is one of the last remaining forests in the area.

The Oluwa Forest Reserve, covering about 678.06 km2, is a tropical rainforest and one of the most important reserves in the country because of its rich biodiversity.

A 2007 Nigerian Conservation Foundation report showed elephants and chimpanzees still inhabit the forest. Some researchers from the Federal University of Technology Akure (FUTA) in the state, who were conducting a survey, were said to have had four sightings of chimpanzee groups in the forest between September 2011 and February 2012. The 2007 conservation report made a recommendation that protected areas should be established in the natural forest.

According to satellite data from the University of Maryland visualized on Global Forest Watch, Oluwa Forest Reserve lost about 14% of its primary forest cover between 2002 and 2020, and preliminary data showed forest loss likely surged higher in 2021.

The researchers from the university said an axis of the forest reserve has been completely cultivated for farming, and there is pressure to convert other parts of the natural forest into farmlands, which would make it difficult for the chimpanzees to inhabit the forest.

Mark Ofua, spokesperson for the Wild Africa Fund, an international wildlife conservation organisation, said cutting down forests to make room for agriculture is one of the major drivers of deforestation and habitat loss in Nigeria.

“Forest reserve clearing results in the felling of iconic trees that have taken hundreds of years to grow and may be endemic to these areas. This means some of these can never be recovered. The loss of forest cover on these reserves also means we may forever lose some of the iconic animals that inhabit these forests,” Ofua said.

“This biodiversity loss is a major driver of climate change and fosters hardships in our environment. Nigeria as a country has over the years lost a significant portion of its biodiversity, and this unprecedented level of forest reserve clearing, as is happening in the Oluwa forests in Ondo state, the Agodi area of Oyo state, will drive what’s left in these areas to the brink of extinction.

“A state of emergency should be declared in the effort to save our forests and forest reserves. The current law that puts the powers/ownership of these forests in the hands of state authorities, who make it their primary objective to amass as much wealth as possible, even if it means driving our forests to extinction, must be reviewed. The Oluwa Forest Reserve in Ondo state must be protected at all costs. It is a natural habitat for pangolins, bats, and other fauna and flora, and a travel path for our few remaining elephants.”

On his part, Chinedu Mogbo, conservationist and founder of Greenfinger Wildlife Initiative, said aside from the fact that revenue will be generated from the cash crops, there are a lot of disadvantages to using the forest reserve for large-scale farming.

“It leads to the loss of large land masses of forests, rendering numerous animals vulnerable, losing carbon sinks, fostering more human-wildlife conflicts, and breaking the threshold for disease transmission from wildlife to humans. This large-scale farming will favour the use of chemicals, which will affect soil and disrupt the ecosystem and other nutrient cycles,” Magbo said.

“Many of our flora and fauna are listed as threatened or critically endangered species. The consistent destruction of forests that house many of these species will ultimately lead to their extirpation.”

Meanwhile, the Idanre forest reserve (OA5) in the state is also facing the same conflict as the Oluwa forest – with the same investor, SAO Agro-Allied Services Limited.

The farmers in the reserve took the state government to court over the alleged sale of their cocoa plantation to the investor. The farmers, who had cultivated cocoa in the forest for over two decades, took to the streets to protest after their farms were graded for the firm to plant palm trees.

The Idanre reserve is a protected natural forest and an important conservation area for the local flora and fauna.

Information on the website of SAO Agro, the company at the heart of the conflict in the forest reserves, stated that the firm is the lead investor developing the Ondo Special Agro Processing Zone supported by the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the Ondo government in the bid to increase state IGR through national and international agricultural trade.

This reporter reached out to SAO Agro through its corporate emails, website, and phone calls, seeking information on the agricultural activities of the investment company in the forest reserves in Ondo state and whether it is aware of its negative effect on the conservation of the depleting forest. Further questions were asked on the alleged involvement of the company in the assault of farmers in the forests. But there were no responses from the company.

In his reaction, Ebenezer Adeniyan, chief press secretary to Lucky Aiyedatiwa, the new governor of Ondo, said the issue was inherited from the past administration in the state. He said he was unsure if the matter had caught the attention of Aiyedatiwa, who was the deputy governor in the previous administration.