Mawphlang/Cherrapunji/Shillong: As he walked around the sacred forest grove, government pump operator and village council member Borhlang Blah, 27, recalled a time when it rained at least once during the summer monsoons for nine days and nine nights without a break.

Everything came to a standstill: adults skipped work, children skipped school, and markets stayed shut in Blah’s home village of Mawphlang, an hour’s drive from Shillong, capital of the northeastern state of Meghalaya.

The rain of nine days and nine nights is now a childhood memory, reduced to no more than two or three days at a stretch.

“The changes in rainfall affects our crops,” said Blah, who gets his last name from the local Blah tribe, traditional protectors of the 200-acre sacred grove, which is the size of 150 football fields and offers a cornucopia of medicinal plants, pink rhododendrons and towering oaks. “The orange is no longer as sweet as it was once, and the size of the fruits that we grow is much smaller.”

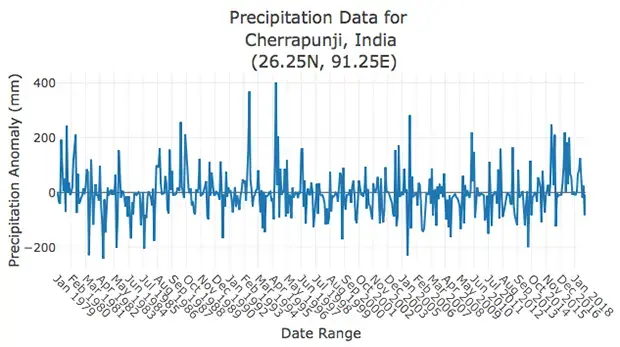

At first glance, the data do not appear to record Mawphlang’s decreasing rain: The monsoon rainfall over Meghalaya—literally, abode of the clouds—was unchanged for 32 years to 2012, and the annual rainfall increased 11.5 mm per year, according to a 2017 Indian Institute of Technology - Gandhinagar (IIT) study. The average temperature rose 0.031 deg C every year over these 32 years.

“This is a significant rise,” said NH Ravindranath of the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bangalore, co-author of a 2018 report that studied changes in Meghalaya’s forests. “IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] reports talk of temperature changes of 1.5 to 2 degrees but over centuries. This change was in just a few decades.”

What has happened in Meghalaya, said experts, is in line with global-warming trends: “rainfall variability” has increased, meaning as it becomes warmer, the rain is more uncertain than ever before, with more intense rain and more dry days.

As one of India’s greenest states with 80 percent of its area under forests and trees, three times the Indian average, Meghalaya is unique and uniquely vulnerable, and most vulnerable are its irreplaceable rainforests, the survival of which holds lessons for the rest of India.

This is the sixth story in our series on India’s climate-change hotspots (you can read the first story here, the second here, the third here, the fourth here and the fifth here). The series combines reporting with the latest scientific research and explores how people are adapting to the changing climate.

From local tradition to global funding

In Mawphlang, Blah’s father and village secretary Tambor Lyngdoh is part of the Khasi Hills Community REDD+ Project, which started in 2007 as a village movement to revive and strengthen sacred groves by making sure the trees were not cut, the produce, such as fruit and mushroom, was untouched, and animals were not poached.

The Mawphlang project has received international funding since 2011 and is India’s first REDD project, a United Nations programme to mitigate the impact of deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries.

When forests are cut, large amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) are released into the atmosphere and temperatures rise. Human activities have already warmed the world by 1 degree Celsius, according to a September 2018 report by the IPCC, the world body for assessing science related to climate change.

Mawphlang is the largest of about 200 sacred groves in Meghalaya, and its preservation—the government hopes—will be an exemplar of what is possible. Over eight years, the project has expanded to 62 villages by involving local councils called Himas; the target is to revive 27,000 hectares of forests—that’s roughly the size of Pune. “If sacred groves were to extend to the entire Meghalaya we will be able to reverse the damage caused by climate change,” said Lyngdoh. The Meghalaya government, which works closely with Lyngdoh, in 2018 received World Bank funding to manage its resources better. Using this money, the government hopes to offer incentives—whether cash or otherwise—to communities, so they protect patches of forests in village backyards.

The urgency for Meghalaya is evident.

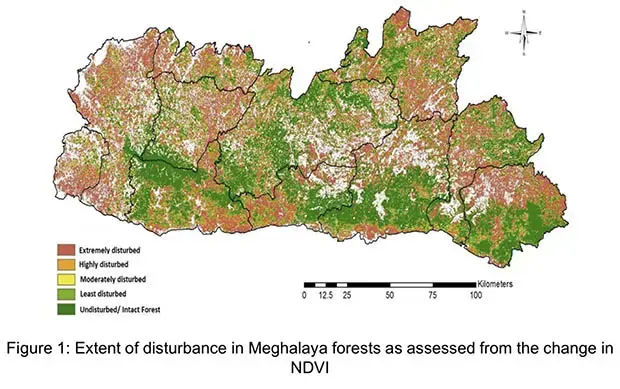

Over 16 years to 2016, nearly half of Meghalaya’s forests experienced an “increase in disturbance”, and around a quarter are now “highly vulnerable” to the impact of climate change, found a 2018 study commissioned by the state government and carried out by the IISc. The forests are disturbed by infrastructure projects and logging, and once that happened, recovery is difficult, said experts.

Cherrapunjee and Mawsynram in Meghalaya continue to receive some of the highest rainfall in the world, but monsoon rainfall patterns have deviated from the long-term mean over 32 years, the IIT Gandhinagar study found. The East Khasi Hills, home to Cherrapunjee and Mawsynram, have faced five to six drought years over this period, compared to three to six years for the rest of the state, said the IIT Gandhinagar study.

Apart from Meghalaya, forests decreased in eight other states and three union territories in India over two years, according to a 2017 Forest Survey of India report. Odisha (885 sq km), Assam (567 sq km) and Telangana (565 sq km) showed the highest decline in forest cover, each losing forests nearly the size of the city of Bengaluru or more.

“Forests in the whole of MP and those in Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, and even Karnataka are prone to forest fires, have low density and the organic carbon in the soil is very low,” said BK Tiwari of the Department of Environmental Studies at North Eastern Hill University (NEHU). “These types of forests are not sustainable or healthy.”

Overall forest cover in India has increased, officially, by 6,778 sq km or nearly twice the size of Goa—as per data that rise from a flawed definition of “forest cover,” as FactChecker reported in July 2019. Part of this rise is attributed to afforestation measures and plantations. “Plantations are not biodiverse,” said Tiwari. “Unlike natural forests they are neither stable nor sustainable. They can be called equivalent to a forest but not equal.”

Part of the reason for India’s receding forests is a long-running conflict over ownership between the government and 200 million Indians who live in these forests. When in February 2019 the Supreme Court ordered the eviction—the judges later stayed their own order—of forest dwellers from their traditional homes, a nationwide controversy broke out because the government’s rejection of 46 percent of land-right claims was flawed and, often, illegal, as IndiaSpend reported in March 2019.

Meghalaya, as we said, is unique because almost all the forest land is controlled by its people. But that has not stopped the march of deforestation and climate change.

Papayas in Shillong and other problems

On a February morning cold enough to require a thick jacket, Blah pointed to the empty spaces between the thinning trees of Mawphlang’s sacred grove, untouched stands of rain and other forest.

“As a child I wasn’t able to walk around here without several bushes getting in the way,” said Blah. Towering oak, rhododendron and khasi pine trees still block out direct sunlight in the depths of Mawphlang’s sacred grove, the best protected, according to studies.

You can enter Meghalaya’s sacred groves on only one condition: Nothing can be taken out.

This rule has enabled Meghalaya—roughly 15 times the size of Delhi—to retain its green cover. Meghalaya stands apart from other states in India because more than 90 percent of forests are owned and protected by its people and not by the government.

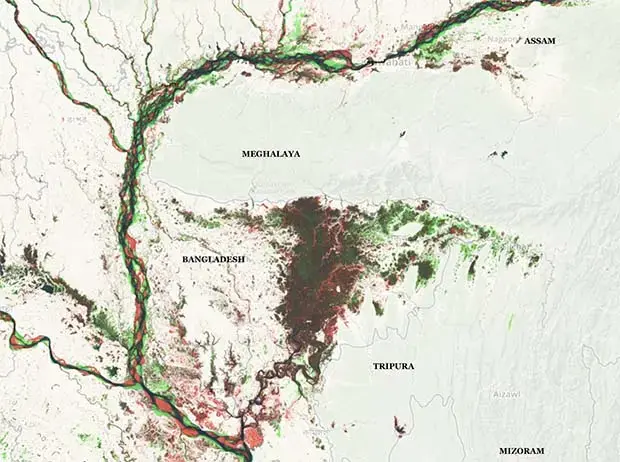

Sandwiched between Assam in the north and Bangladesh in the south, Meghalaya is a part of the Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot—one of the most threatened biodiversity hotspots in India after the Himalayas—due to rapid resource exploitation and habitat loss.

The hills of the eastern sub-Himalayas—Garo, Khasi and Jaintia—run through most of Meghalaya, and the rest of the landscape is a high plateau.

While most of India receives 801 to 1,500 mm of rainfall in the monsoon months, Meghalaya receives double of that, according to the 2019 data from the India Meteorological Department (IMD). There is a wide variation in rainfall within Meghalaya. Some areas like Cherrapunji—once famous as the wettest region on Earth—receive up to 12,000 mm of rainfall every year, about five times the amount Mumbai gets.

The Disturbed Forests Of Meghalaya

When locals started complaining of a perceptible difference in rainfall and warm-weather plants like papaya appeared over the last decade in Shillong—where the average day temperature is 17 degrees Celsius—the government commissioned an investigative study.

“We looked at the data, starting from the year 2000, because we have good satellite images for that period,” said Rajiv Kumar Chaturvedi, an assistant professor at the Birla Institute of Technology, Pilani in Goa, and a co-author of the IISc study referred to earlier. Data were also collected manually from 300 locations statewide to understand the impacts of changing climate on biodiversity.

“The places where we saw maximum forest degradation were the places with the most biodiversity,” Chaturvedi said. The annual mean minimum temperature has increased by 0.6 percent between 1951 and 2000, the IISc study found.

The fragmentation and isolation of once contiguous forests because of infrastructure projects is also why a fourth of Meghalaya’s forests are now vulnerable to climate change. “Fragmented forests don’t recover from the impact of temperature and rainfall changes like natural forests do,” said Ravindranath from IISc.

Development activities were as much to blame, the study confirmed. “You can’t cut trees in a place, clear forests for plantation or build right through a forest and then call [the effects] climate change,” said NEHU’s Tiwari.

In February 2019, a NASA image that showed the earth greener than it was 20 years ago—led by India and China—went viral and was taken out of context. The rise in the greening of the planet was attributed to agriculture and afforestation, which do not provide ecological benefits, such as cooling the air or supporting biodiversity, as forests do.

The biodiversity issue is particularly relevant to Meghalaya, home to some of India’s last stands of rainforest.

Why rainforests are important

A sq km of rainforest can harbour as many as 1,000 different plant species. That is more plant species in Europe and North America combined.

India’s rainforests are primarily scattered across the Western Ghats, along the country's western coast and parts of the Eastern Ghats along the east coast. Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya and Assam in the northeast are the other areas that support such forests.

Around 10 percent of Meghalaya's forests are tropical wet evergreen forests or rainforests. Several species of plants and animals—vultures, frogs, turtles and orchids—in Meghalaya’s rainforests are “critically endangered” or “vulnerable.” These are endemic to the region, found nowhere else in the world.

Meghalaya’s sacred groves, some of which are rainforests, are home to 1,886 plant species, including orchid, bamboo, timber and medicinal plants. “Since there is plenty of sunlight and water, plant productivity in a rainforest is high,” said Kenneth James Feeley, professor at the University of Miami, where he studies tropical forests and climate change. “This allows several insects and fungi to grow which in turn become food for other animals.”

It is these forests that Meghalaya is losing, a decline, the government hopes, can be halted by local communities.

Homestays and other benefits

In 2011, as word of the Mawphlang REDD+ project spread, sisters Icylian, 47, and Castilian Wankhar, 42, realised that conservation was drawing in more tourists, some from as far as Europe. They opened their homes to the tourists, giving them another source of livelihood.

“The number of tourists has gone up in the past decade. We have someone or the other living with us most of the year,” said Castilian. Other homestays, too, have opened.

Icylian, an English schoolteacher, remembered a time when, as young girls, they picked mushrooms and filled pots of water from the ponds inside the sacred grove.

Many of these ponds are now drying, a sign of the forest’s ill-health.

“Forests act as a sponge,” explained the University of Miami’s Feeley. When it rains, forests absorb water and release it over a period of time. As trees are cut, the water runs off quickly and increases the chances of floods, erosion and even droughts. “Having forests is good for the community that depends on the water bodies.” Around 60 of Meghalaya’s sacred groves are located at the source of perennial streams, playing a crucial role in soil and water conservation. “Almost 90 percent of our water flows directly to the neighbouring state of Assam and Bangladesh,” said L Shabong, officer on special duty and head of the Institute of Natural Resources at the Meghalaya Basin Development Authority (MBDA). “This has impaired nearly 54 percent of our natural springs.”

As Meghalaya’s forests thin, parts of Bangladesh receive excess water during the monsoon season, causing floods, and then face water scarcity during the winter.

Changes In Surface Water In The North-East, 1985-2015

But policy making to arrest the slide is a bit of a shot in the dark.

One of the biggest challenges for Meghalaya, and other states in the northeast, is that even if they were to collect detailed climate data, there is no research institute in the region to analyse these data. Only a handful of institutes across India can, and that is not enough to study the impact of climate change across sectors, said the IISc’s Ravindranath. He is set to lead a pan-India study on the impact of climate change; it will be ready over the next six months.

“We simply do not have the data to make informed policy,” said Ravindranath. “We can only provide broad trends.”

Since the trends have been clear—uncertain rain, fewer benefits from the grove—Mawphlang’s people are enthusiastic about reviving traditions.

The villagers are currently working together to identify patches of degraded forests, to which they can restrict access to allow natural regeneration. Some of the villagers are adopting patches of forests and nurturing them personally, weeding out, for instance, any new species not native to the area.

As they work with the government to increase supplies of cooking gas, community leaders are also persuading villagers to stop using firewood for cooking. A typical Khasi household consumes 15 to 20 kg of firewood daily.

Blah, too, is building a homestay. For a decade he, and his father, Lyngdoh, the village secretary, hosted two tourists every night at their homes. In 2017, they began building a new homestay. Some of the rooms are ready, and as many as 15 tourists can stay overnight. Lyngdoh is proud of the livelihood opportunities that conservation affords to his people. “People love the experience of living here,” said Lyngdoh.

But tourist satisfaction is only a part of the effort to rejuvenate the sacred grove.

“As a state we’ve taken a lead in adapting to changing climate, and we think other states can learn from us,” said Shabong, the government officer at MBDA.

The sacred-grove project has enhanced Lyngdoh’s reputation, and government officials now consult him if they need the support of other tribal leaders. For Lyngdoh, this is a vindication of his traditions, that the elders of his tribe knew what they were talking about.

“We already know how to conserve the forests,” said Lyngdoh. “We have been doing it for centuries. All we need to do is support and help spread the tradition.”

Support for this reporting was made possible by the Rainforest Journalism Fund, in association with the Pulitzer Center.

- View this story on Business Standard

- View this story on The Quint