This story was reported by Mongabay’s Brazil team and first published here in Portuguese on their Brazil site on June 9, 2021.

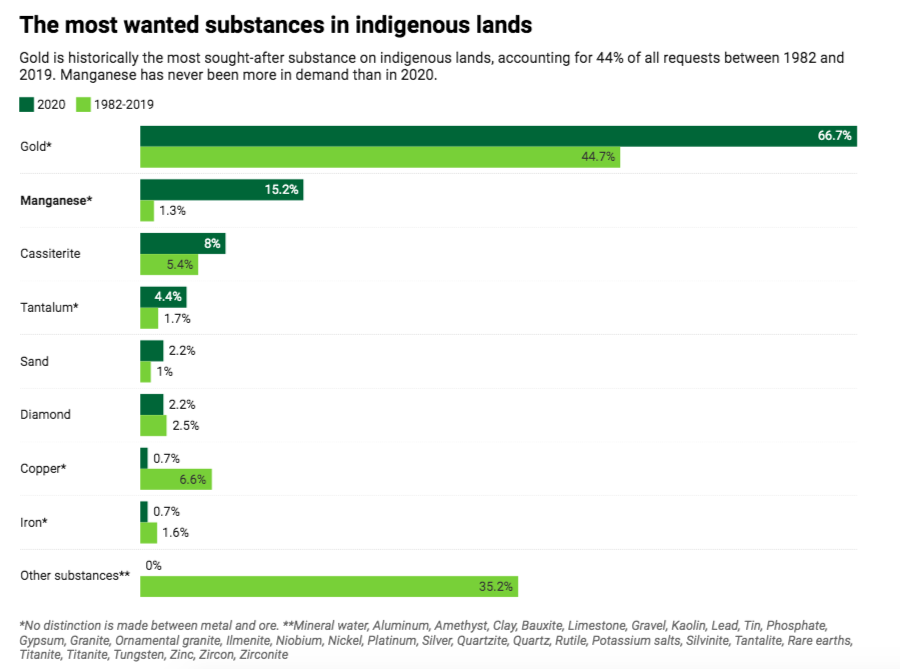

Demand for manganese in China is having a huge impact on the other side of the world: for the Indigenous Kayapó people in the Brazilian Amazon. The metal is essential for the manufacturing of steel used in new public infrastructure works in China, and the high demand has pushed its price up on the international commodities market. In Brazil, one of the world’s biggest producers of manganese, that’s led to a surge in illegal mining — in particular in the Kayapó Indigenous Territory in Pará state.

“The Federal Police have been seizing trucks with manganese almost weekly at inspection points in the interior of Pará,” the National Mining Agency (ANM) said in February through its press office.

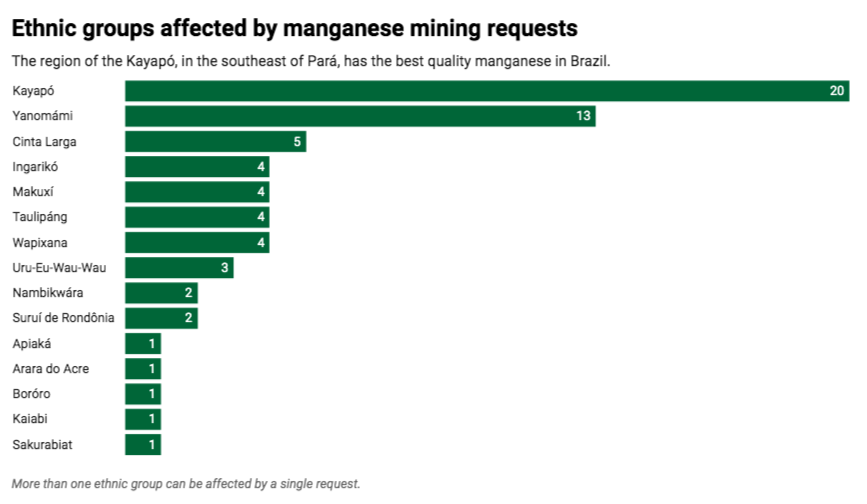

According to the ANM, the illegal manganese comes from southeastern Pará. In this region, on the outskirts of the Carajás mining complex, the Kayapó people live atop some of the richest mineral deposits in the world.

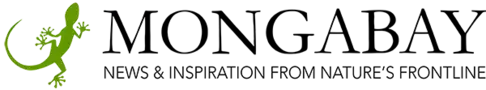

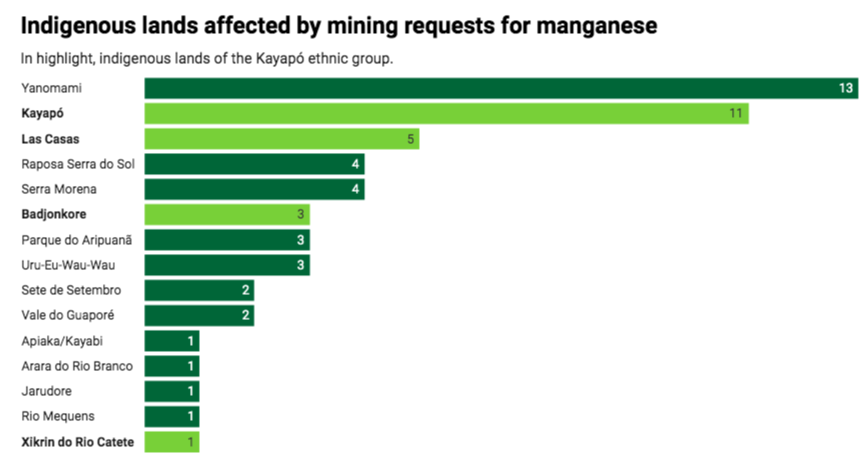

The Amazônia Minada project, which monitors formal applications to mine on Indigenous lands — a practice banned under Brazil’s Constitution — has detected an unusual rise in requests to mine for manganese. The metal typically accounts for just over 1% of such requests, but last year made up 15% of the total. Most of the applications targeted the Kayapó territory.

Though the applications filed with the ANM merely signal interest, they can also open the way for illegal extraction. In the Kayapó territory, the Indigenous population is already contending with miners seeking the mineral. “We see the traces of people who have been digging there,” said a Kayapó individual who asked not to be identified. A 2019 report by Funai, the federal agency for Indigenous affairs, has denounced the problem.

Illegal mining of manganese isn’t a recent phenomenon, the ANM said, “but it has been intensifying.” The agency also confirmed that a recently interdicted shipment of illegal manganese was destined for the Asian market. “The upsurge seen in 2020 reflects the international demand for steel, iron, alloys and batteries, the currency devaluation, as well as the expectation of impunity due to insufficient personnel for field inspections. All this worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic,” the ANM said.

Widely seen as stoking this problem are the environmental policies of President Jair Bolsonaro, as Mongabay previously reported.

Surge in manganese mining applications

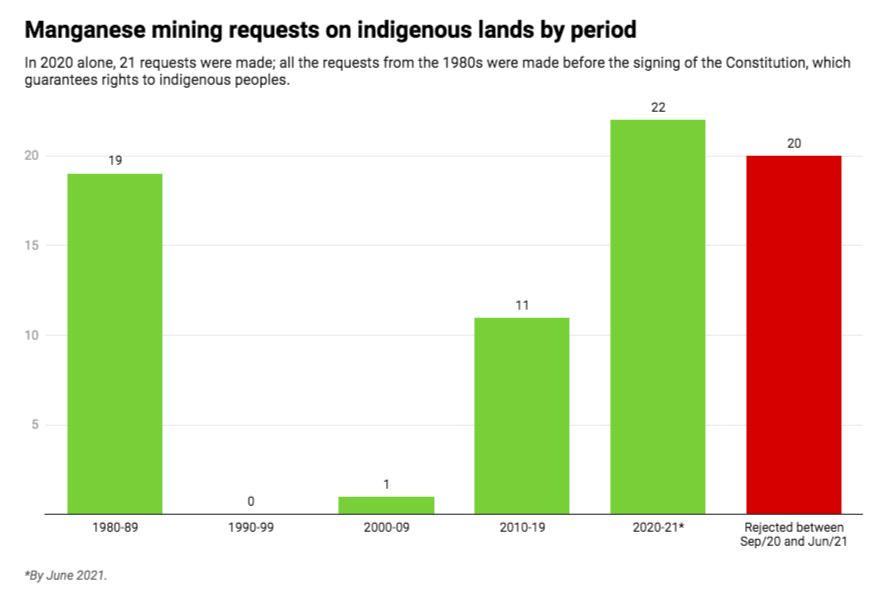

There were 21 applications registered in 2020 to mine for manganese on Indigenous lands. That’s almost as many as for the entire period between 1980 and 2019. Adding the one application registered by June 4, 2021, this new decade, just 17 months old, has broken the records of the previous decades.

In fact, the total number of manganese mining applications filed with the ANM in 2020, at 38, surpassed the total number since the 1980s. But between September last year and June 2021, 17 of these applications were rejected by the agency because they overlapped with Indigenous areas. Another two requests had their original areas adjusted and now target areas adjacent to Indigenous lands.

The rejection of mining applications that overlap with Indigenous lands reflects an order of the Federal Public Ministry, which has filed lawsuits requesting they be cancelled since there no laws permitting mining on Indigenous lands. “Based on this argument, three applications filed in 2021 were rejected by the ANM,” the agency said.

Despite this, it maintains that applications cannot be rejected when they enter the system.

“At the time of Brazil’s Constituent Assembly in the late 1980s, the Minister of Mines and Energy Aureliano Chaves established an odd procedure for mining requests on Indigenous areas, which is still in place,” said Marcio Santilli, founder of the Instituto Socioambiental (ISA), which advocates for Indigenous and environmental rights, who participated in the debates during the drafting of Brazil’s 1988 Constitution. “When they enter the government register, they are neither rejected nor authorized. They persist like Snow White, waiting for the kiss of the prince to awaken. This kiss is the regulating law.”

The Amazônia Minada project has revealed cases where the mining agency authorized prospecting even when the requests overlapped with Indigenous lands.

As a non-profit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund reporting across the world’s tropical rainforests. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

In February 2020, President Bolsonaro presented a bill to Congress to regulate mining on Indigenous lands — the “kiss of the prince” the mining companies are waiting for. “Many attempts have been made, but this is the worst I’ve seen because it doesn’t acknowledge the constitutional protection of protected areas,” Santilli said.

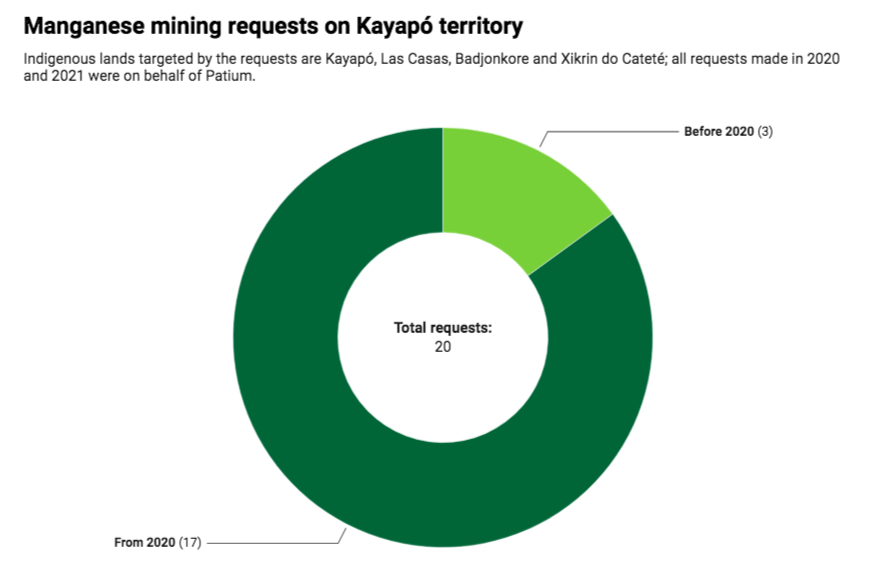

Company with the most mining requests targeted by police

Sixteen of the 17 rejected requests in 2020 were made on behalf of a single company: Patium Beneficiamento de Minério. All of its applications targeted the Kayapó Indigenous Territory. Patium has another 17 requests pending to mine for manganese, 11 of which overlap with the Kayapó territory, and three each with the Badjonkore and Las Casas indigenous territories. All three reserves are home to the Kayapó people. The company has by far the highest number of requests to mine for manganese within protected areas.

Up to this year, Patium was one of 12 companies in a conglomerate linked to businessman Samuel Borges, whose main brand is RMB S.A., the Portuguese acronym for Mineral Resources of Brazil. It’s one of the few companies authorized to explore for manganese in the Carajás mining complex, considered to have the best deposits in the country and among the purest in the world.

Patium was sold in early 2021, but three other Borges-linked companies have applications pending to mine within Indigenous areas, including RMB S.A. itself and RMB Manganês, a subsidiary.

The ANM said it “does not grant any permission on Indigenous land” and that “requests may be filed but will not succeed after analysis.” Yet despite this claim, in 2017, it granted authorization for prospecting for two applications from RMB Manganês that overlapped with Las Casas Indigenous Territory. One of the applications was for manganese, the other for copper.

The company has justified its requests, saying the permits granted “are not located within Indigenous lands, but in the bordering neighborhoods.” But Amazônia Minada, using publicly available data from ANM’s own system to generate maps, has detected an overlap with the protected areas.

Through its press office, RMB S.A. announced that it was dropping mining bids on Indigenous lands filed on behalf of its subsidiaries. “We understand that the regulation of this matter is discussed in the National Congress and that it would not be viable at the moment to keep these requests in our portfolio,” it said. But all of the applications remain active in the ANM registry.

In 2020, another issue involving RMB Manganês caught the attention of the authorities. The Federal Police and the ANM found 81,100 tons of manganese “with evidence of illegality” in the company’s warehouses in the port of Barcarena and at the company’s headquarters in Curionópolis. This was the second-largest seizure last year, almost a third of the 305,000 tons seized in 2020 by authorities.

In addition, the company owes 8.9 million reais ($1.8 million) to the state, arising from unpaid taxes and social security contributions for its employees. Another company in the group, AllMineral Ltda, owes 120,000 reais ($24,000) in public debt. Borges, the group’s CEO, owes 55,000 reais ($11,000) in taxes and is listed in the federal registry of tax delinquents. At the same time, his companies are valued at more than 6 million reais ($1.2 million), according to the federal tax office.

RMB S.A. said it has renegotiated part of its debts with the tax authorities and is disputing a certain undisclosed amount in court. “The RMB Group emphasizes that it does not participate in or approve any illegal activities. Its business is based on sustainable practices, rules of compliance and cooperative governance. The group does not only focus on returns to shareholders, but also on sustainable development, as well as employment and income for the regions where it operates,” it said in a statement, which can be read here.

New conflict between Vale and the Xikrin

Of the 53 requests to mine manganese on Indigenous lands analyzed by the Amazônia Minada project, eight were approved for prospecting (though not mining) by the ANM — contrary to the agency’s commitment not to allow any kind of mining-related activity in demarcated areas. This approval includes the extraction of ores even if only for assaying purposes.

One of these applications stands out because it was approved more than 30 years after being requested, and because it threatens to intensify a conflict between the Xikrin Indigenous people, one of the communities of the Kayapó people, according to the Instituto Socioambiental, and Brazilian mining giant Vale S.A.

The Xikrin are suing Vale for harm caused to their community by three of its mining operations around the Xikrin do Cateté Indigenous Territory. The most prominent case is that of Onça Puma, a mine located 6 kilometers (4 miles) west of the Indigenous territory. According to a report by the Federal University of Pará, Onça Puma is contaminating the Cateté riverbed with heavy metals, compromising the health and daily life of the Indigenous community.

Now Vale is exploring, under a prospecting research permit, a manganese deposit that sits at the southern tip of the Xikrin land. The company says it does not seek to prospect or mine on Indigenous lands in Brazil. But in October last year, it informed the ANM that it also found copper during its surveys in one of these areas. Vale has also paid the annual fees required to maintain the bid for manganese located on the Xikrin do Cateté Indigenous Territory.

There are currently at least 75 mining bids registered in Vale’s name that overlap with Indigenous territories throughout Brazil. This figure doesn’t include applications filed by subsidiaries and affiliates of the company. The company said it is dropping these processes; the current figure is lower than the 137 pending applications in the ANM’s system in January. “Although a larger number of processes in the name of Vale Group companies appear on the National Mining Agency’s website, most of them have been dropped by Vale, pending only updating or rejection with ANM,” it said.

2,000% above the safe limit

If mining for manganese is allowed in the Xikrin do Cateté Indigenous Territory under Vale’s name, it may worsen the health condition of the population. Reginaldo Sabóia, a researcher from the Federal University of Pará who studies levels of heavy metals in hair samples, the Indigenous community is in danger. “These people present an index of manganese contamination that will impress any professional with knowledge of the case,” Sabóia said in a report from February of last year.

His tests detected manganese levels in the Indigenous people that are 500% in excess of what’s considered safe for humans. Two village elders, Kokono Xikrin and Painho Xikrin, have accumulated 2,000% more than the tolerable limit. “Extraordinary,” Sabóia wrote in his report.

“Of the metals found in the bodies of the Indigenous people, manganese had the highest accumulation. If not urgently treated, it will cause devastating and irreversible health damage,” he added. According to a study conducted by Fiocruz, Brazil’s leading medical research institute, the toxic effect of manganese immediately impacts the lungs and the central nervous system, “causing clinical neurological conditions and inflammation of the upper respiratory tract.”

At the start of the coronavirus pandemic, a respiratory disease that attacks the lungs, the inhabitants of the Xikrin do Cateté Indigenous Territory registered the highest percentage of deaths from COVID-19 in Pará. Since then, the whole community has been vaccinated.

Sabóia attributes the high levels of manganese in the community to Vale’s operations. The company denies that its activities around the Indigenous area are polluting the river or harming the health of the local community. The dispute has gone to court, but the case has been suspended until the end of this year. During a mediation hearing between Vale and the Xikrin, a decision was made that, according to the company, “aims at creating a favorable and harmonious environment for the construction in a joint and participative way, in agreement that judicial actions are concluded.” The full response from Vale can be read here.

‘Everything a mining company wants’

The figures disclosed by the Amazônia Minada project shed light on the realities facing the largest tropical forest on the planet: while it may be home to thousands of Indigenous people, the Amazon also holds below its surface precious treasures that draw mining companies. The region where the Kayapó live is especially prone to conflicts because it includes the notorious mining complex of Carajás. This geologically blessed location is rich in gold, copper, iron and manganese deposits of exceptional quality.

The manganese found in Carajás has a purity of 80%, thanks to the process of time. “This deposit was formed 2.75 billion years ago,” said geologist Raphael Neto, from the Geological Service of Brazil. It can be difficult to imagine, but the formation of the deposit goes back to a time when the region that today is covered in forest was an immense sea, when the Earth’s atmosphere was being formed. First dissolved in water, then shaped by oxygen and finally reshaped by the shifting tectonic plates, the metal acquired an exceptional quality.

“All metal from Carajás is pure, it is everything a mining company wants because it lowers the cost of mining,” Neto said.

But not all the miners operating in Carajás are authorized to do so. The deposits have attracted miners who supply the illegal market. According to the ANM, there is major illegal extraction taking place “specifically in areas where mining rights are held by Vale S.A., in the region of Buriti and Sereno.”

Apart from Vale’s unexplored concessions in Carajás, it maintains the main manganese-producing mine in Brazil in the region. Known as Azul, the mine has been closed since last year. Vale recently sold part of its mining rights in the region to RMB S.A. The latter wants to “enlarge its participation in the national and international market” for the metal. Neither RMB nor Vale provided details about the deal. “This information is confidential,” Vale said.

According to the authorities, Mineração Buritirama, the largest producer of manganese in Brazil, is operating mines on its concession in Carajás. The company is also under investigation for manganese mining in the Kayapó Indigenous Territory, according to an Indigenous source and an official at Funai, the Indigenous affairs agency. According to Repórter Brasil, the activity is taking place close to one of the company’s concessions, 5 km (3 mi) from the eastern border of the Indigenous territory. Since 2018, the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office has pursued a confidential civil inquiry into the issue.

“We disagree with any illicit activity. Whenever we become aware of any irregularity, we communicate it to the government and the responsible authorities,” Buritirama said. The company’s full response can be read here.

Unlike gold, which calls for the use of mercury to extract the metal from the ore, thereby leading to mercury contamination of rivers and soil, the illegal extraction of manganese is done mechanically. It only needs to be dug up from the soil and sieved. The problem, according to Pará state prosecutor Igor Goettenauer, who investigates illegal manganese mining and trafficking, is that the miners end up exploring in a very superficial way. “When the mine gets deeper,” he said, “they abandon it, increasing the scope of environmental damage.”