This story was produced with support from the Rainforest Journalism Fund in partnership with the Pulitzer Center

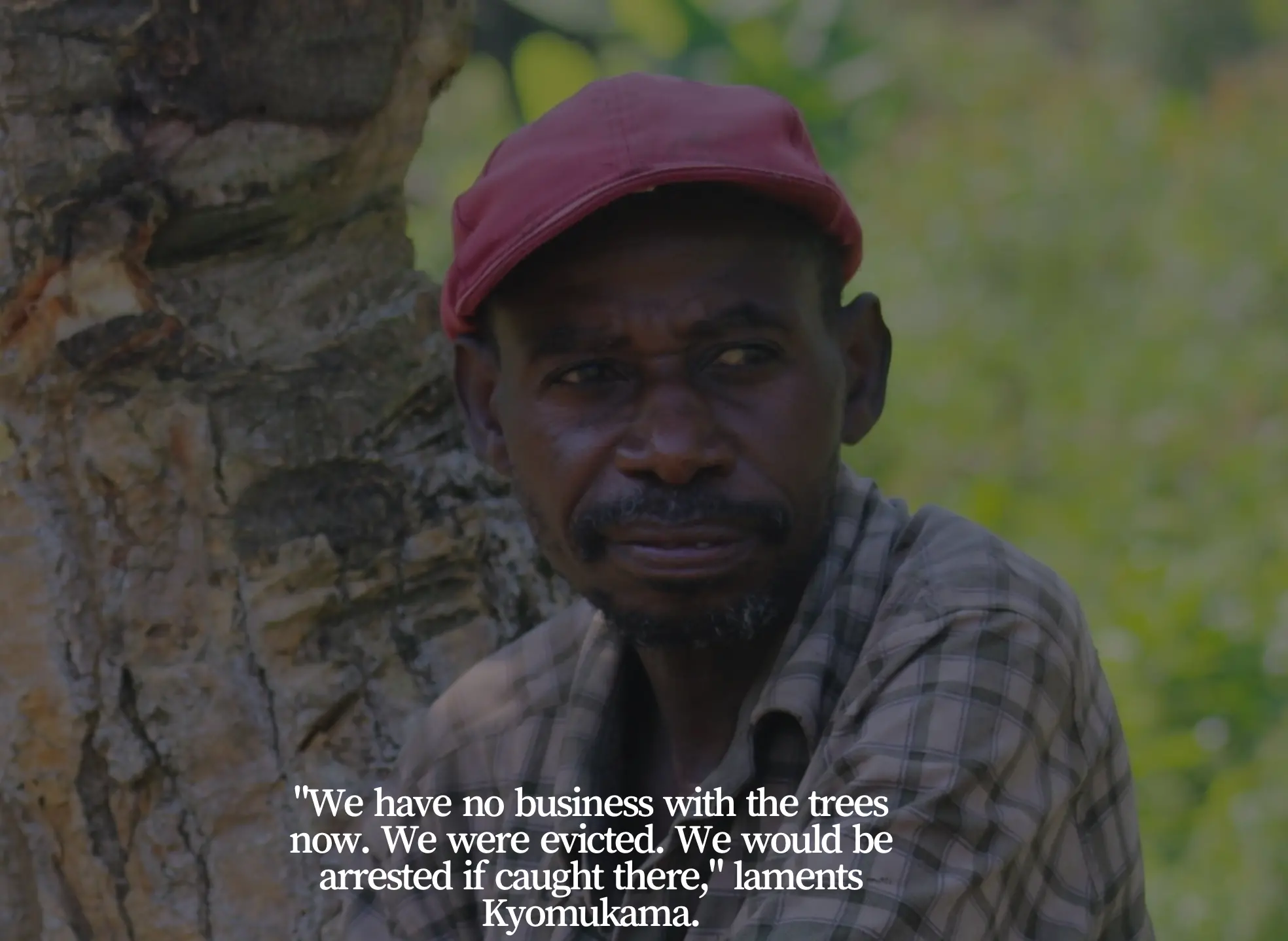

Thirty-one years after Kyomukama Jackson was evicted from Bwindi Impenetrable Forest in southwestern Uganda, the now 48-year pygmy is still hopeful that he will return to his forest-dweller life.

For the first 17 years of his life, Kyomukama, an indigenous Twa pygmy, lived in caves and tree branches, just like his ancestors. This is the life he wants to return to. He says his current life in a two-room iron sheet thatched house is “boring.”

“We depended on trees; we safeguarded them,” recounts Kyomukama, a father of nine and chairperson of the Karehe Batwa group in Buhoma, Bwindi. His ancestors were part of the ecosystem of Bwindi Impenetrable, Echuya, and Mgahinga rainforests in Southwestern Uganda.

“We have no business with the trees now. We were evicted. We would be arrested if caught there,” laments Kyomukama.

Unlike Kyomukama, who pulled out of the management of the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest after he was evicted, Francis Nayituriki, a Twa of Kitabi village in Southern Rwanda, is a community volunteer, working with rangers to control and prevent illegal activities in the Gishwati rainforest.

He has dedicated his life to guarding the forest again, poaching and illegally tree felling for firewood and charcoal.

“My daily routine involves surveying forest blocks to check whether there is any destruction that could be reported to authorities,” notes Nayituriki.

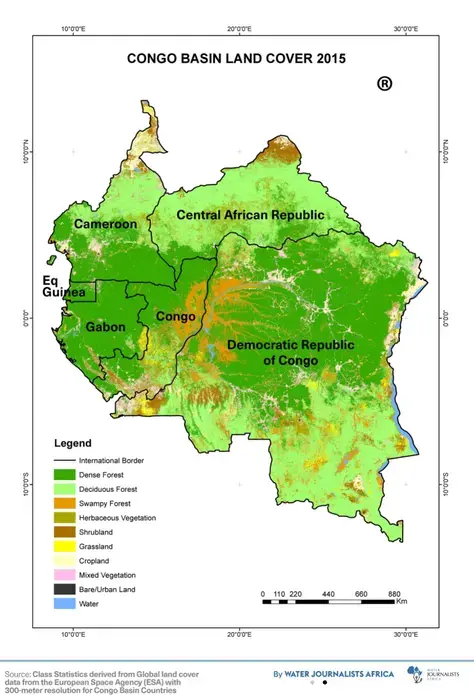

Bwindi Impenetrable, Echuya, and Mgahinga rainforests in Uganda and Nyungwe and Gishwati rainforests in Rwanda are on the far eastern end of the Congolian rainforests belt of lowland tropical moist broadleaf forests. The Congo rainforest spreads from the coast of the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the mountains of the Albertine Rift in the east.

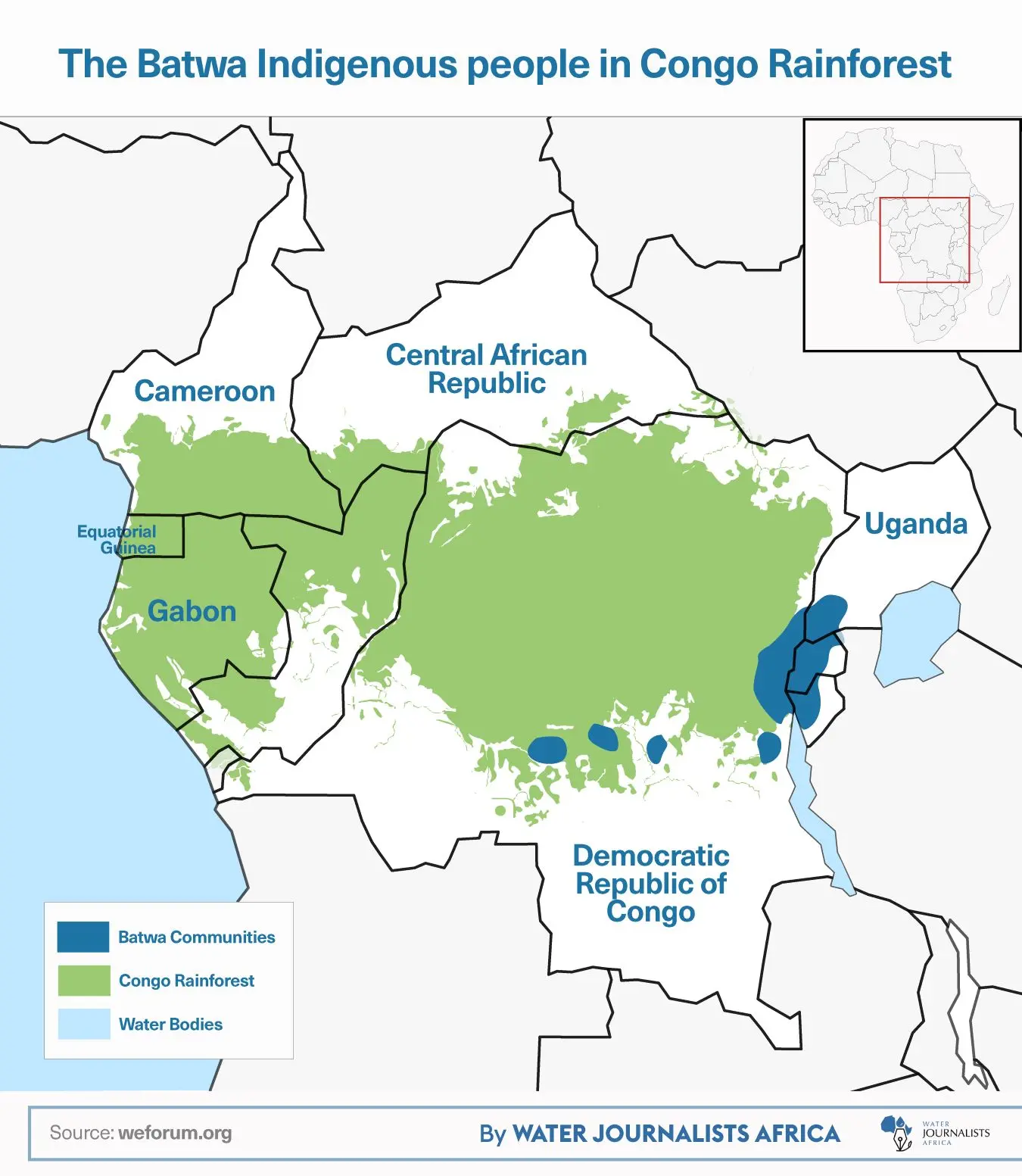

Some of the indigenous people that inhabit this forest are Mbuti, Baka, and Twa peoples, all indigenous pygmies.

Kyomukama and Nayituriki are Twas also known as Batwa. Twa is one of the oldest surviving tribes in central Africa, mainly living within or close to the Congo Basin rainforest, the second-largest tropical rainforest in the world.

According to Stokes (2009) Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East, most Twa populations live in the great lakes region stretching from DR Congo to Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and Tanzania. Others live in Kasai, in DR Congo.

They are part of about sixty million people living within the Congo tropical rainforest that occupy about two hundred million hectares of land.

The government of Uganda evicted the Twas from Bwindi Impenetrable, Echuya, and Mgahinga rainforests to pave the way to create conservation areas for the endangered Mountain Gorillas.

But the Twas in Rwanda have freely been living and interrelating with the tropical forests in the country. They are now playing a significant role in the conservation efforts of the protected tropical forests in the country.

Although the deforestation rate in the Congo basin seems small compared to other regions of the world, it has been increasing over the last three decades, from 0.09% between 1990 and 2000 to 0.17% between 2000 and 2005, according to the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR)

Jeconeous Musingwire, an environmental scientist and manager for the national environment watchdog NEMA in southwestern Uganda, highlights uncontrolled industrial logging, mining, agriculture, expansion of urban centers, and harvesting of trees for firewood and charcoal as the biggest drivers of deforestation in the Congo rainforest over the past three decades.

Twa is one of the oldest surviving tribes in central Africa, mainly living within or close to the Congo Basin rainforest, the second-largest tropical rainforest in the world.

Rwanda's inclusive conservation

In Rwanda, for years, before the current government, plans to conserve the rainforests yielded little effort until a new strategy engaged the Twa indigenous people living within or close to these forests with hopes of fostering a sustainable solution.

The Twa also known as “historically marginalized people,” have now played a significant role in the conservation efforts of the Nyungwe protected reserve, designated as the oldest conserved tropical rainforest in Africa that spans 1,019 km2.

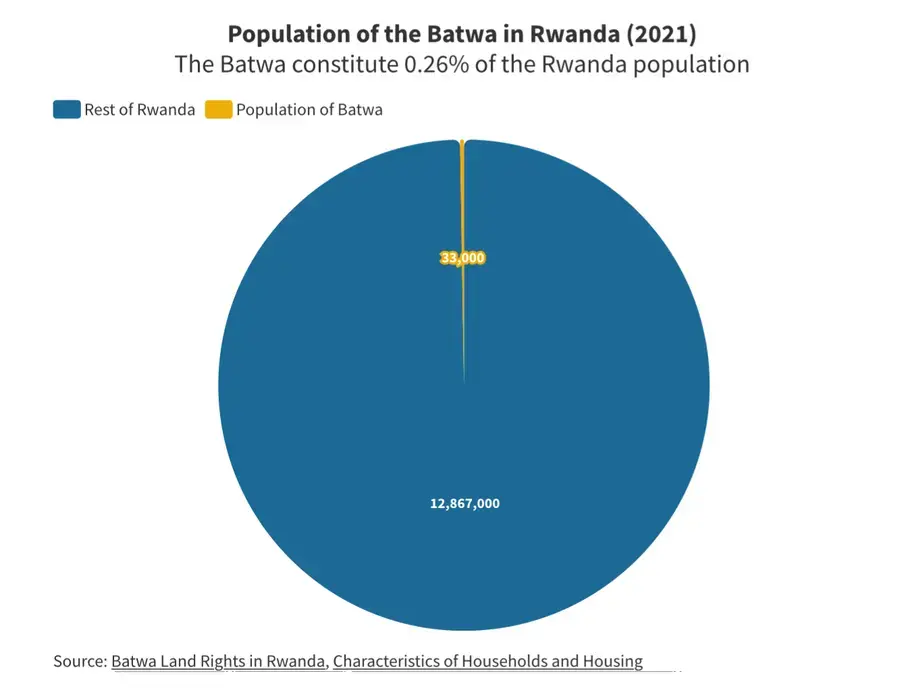

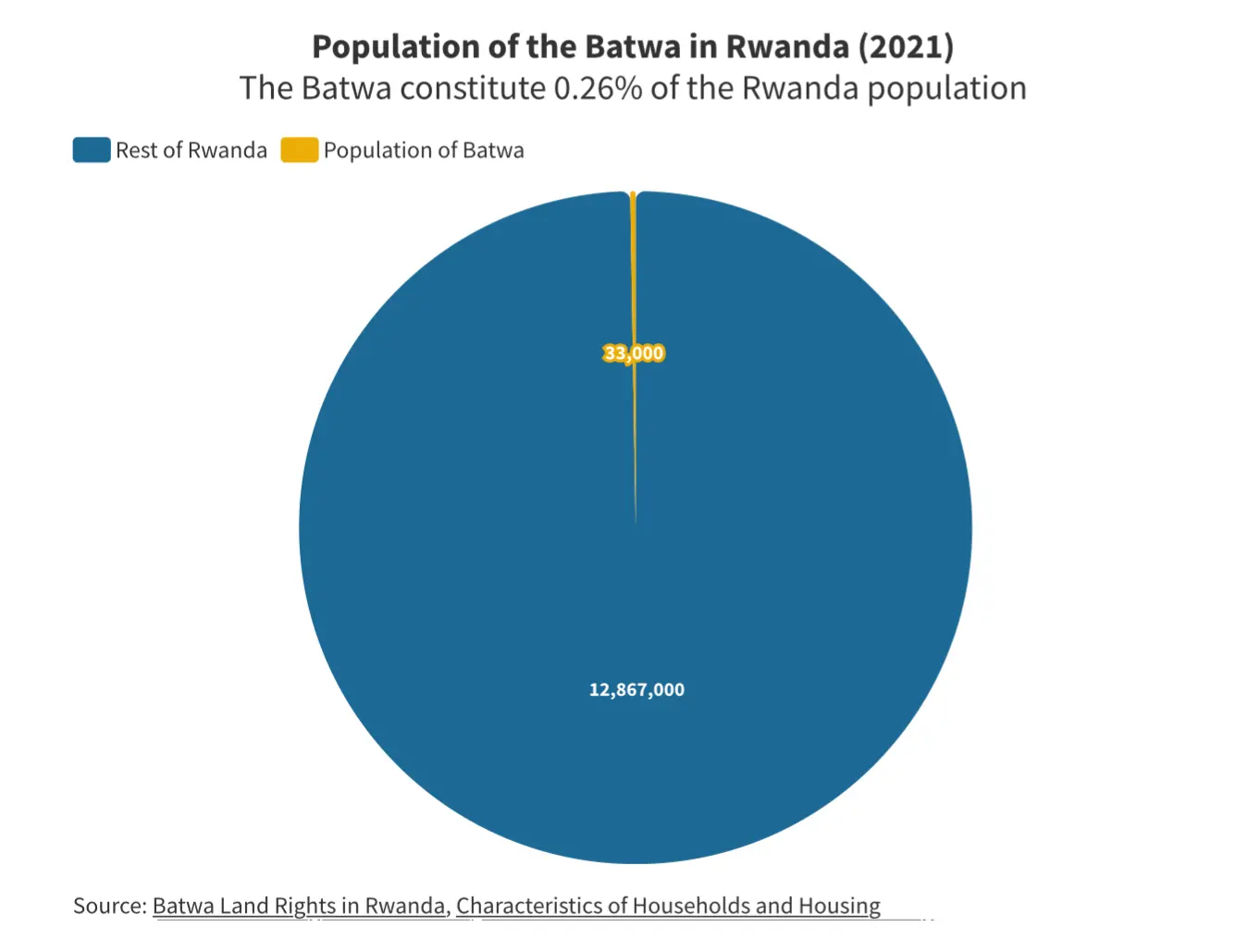

The Batwa constitute 0. 26% of the Rwanda population, according to the National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda.

As part of efforts to stimulate local and indigenous communities involved in the sustainable management of protected areas and parks, the government of Rwanda and its stakeholders instituted various schemes to support indigenous developmental projects.

For example, Twisungane Cooperative members, comprising Twas in Gatare, a village located on the one side of Nyungwe forest, have been supported to invest in income-generating activities, including carpentry, furniture works, and welding.

Less than 200 Kilometres from Nyungwe is the Gishwati rainforest, located in North West Rwanda. This flourishing biodiversity sphere was once on its deathbed due to encroachment and destruction.

The situation was so bad that the forest was almost getting extinct. It decreased from 28,000 hectares in the 1970s to about 600 hectares in 2002, according to data from the Forest of Hope Rwanda.

Laurent Hategekimana, a villager from Nyabihu, a district in western Rwanda, recalls the terrible condition of the Gishwati natural forest a few years ago when illegal loggers and farmers overran it.

He notes that since 2002 the interest in restoring Gishwati Natural Forest has been growing, and the efforts that involve local indigenous communities are paying dividends.

Hategekimana is among members of the indigenous community who have become actively involved in keeping guard of the Gishwati natural forest. They are the forest watchdog. They inform the local administrative authorities of illegal activities such as felling trees without a permit and burning charcoal.

“I now understand the importance of conserving the forest. That’s why I sacrifice my time to protect it,” Hategekimana notes.

Uganda’s fortress conservation

Back in Uganda, the approach used to conserve Bwindi Impenetrable, Echuya, and Mgahinga rainforests and several other forests worldwide that resulted in the eviction of Kyomukama has been described by researchers and advocates of indigenous people as “fortress conservation” and criticized for its adverse effects on the indigenous people.

The fortress conservation model involves creating protected areas to enable ecosystems to flourish in isolation from human disturbance.

This meant that the Twa who lived in Bwindi Impenetrable, Echuya, and Mgahinga rainforests, with a nomadic-like lifestyle — moving from place to place in search of forest resources, hunting wild animals, and honey collection — their forest-dweller life had to end. It was cut short in 1991. The government of Uganda evicted them from these rainforests to pave the way to create conservation areas for the endangered Mountain Gorillas.

“Our lives were divorced from the forests by gorillas; we are struggling to live,” narrates Kyomukama, a father of nine and chairperson of the Karehe Batwa group in Buhoma, Bwindi, Kanungu district, South Western Uganda.

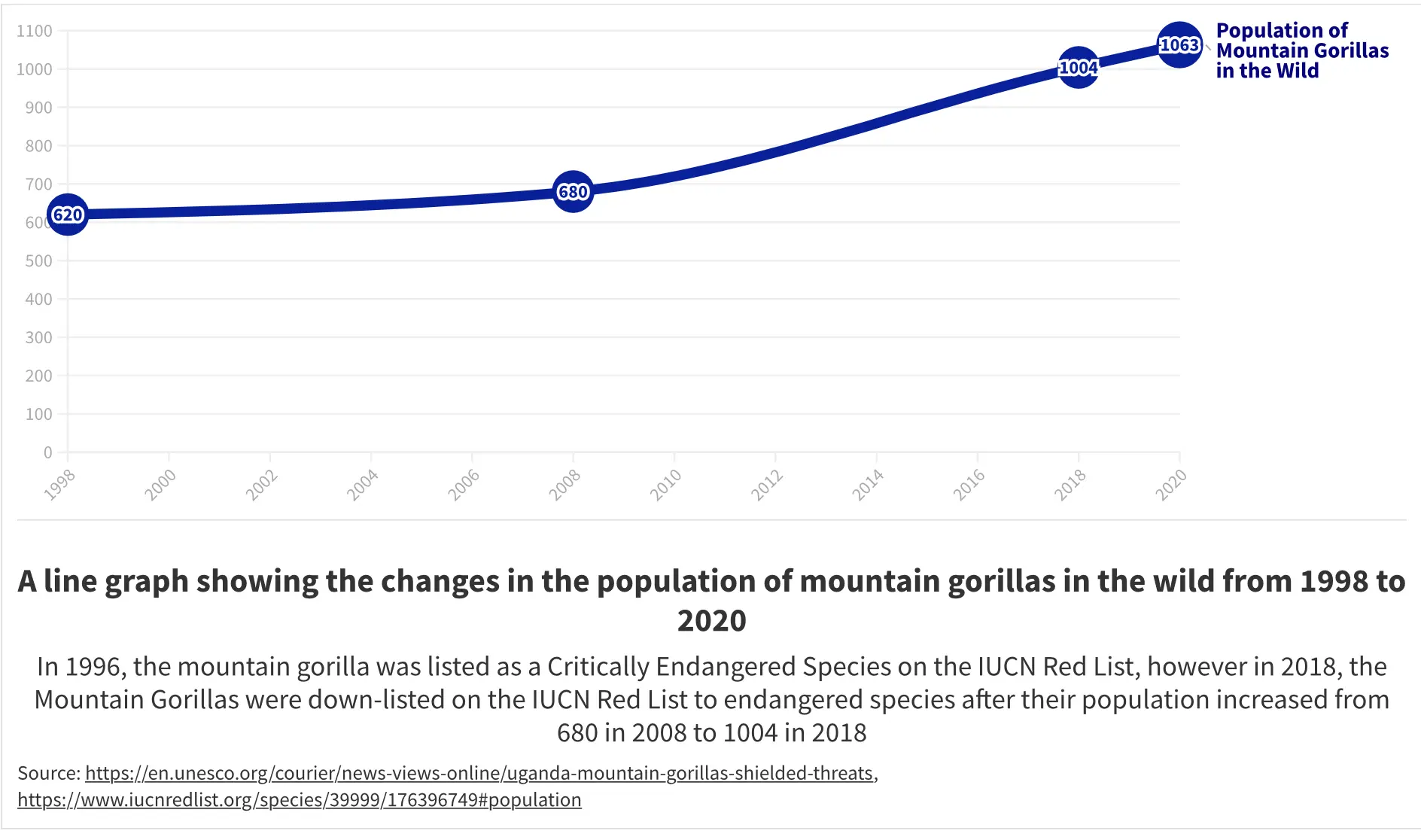

Just about 1,063 Mountain Gorillas on Earth (2018 Mountain Gorillas survey) live in three countries: Uganda, Rwanda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Half of these live within the Bwindi Impenetrable rainforest.

A UNESCO world heritage site, Bwindi Impenetrable Forest was gazetted as a game sanctuary in 1932 to conserve the Mountain Gorillas. The government of Uganda later upgraded it to national park status in 1991. It is home to over 160 species of trees, 100 species of ferns, 120 mammals, and some 350 bird species.

Conserving Bwindi Impenetrable Forest for gorillas meant human activities in the forest had to be minimized; the reason why the status of the forest changed from multiple uses of the resource to nature conservation.

And in nature conservation, argues Jeconeous Musingwire, an environmental scientist and manager for the national environment watchdog NEMA in southwestern Uganda, “there is no human activity.”

“Whenever there is an icon of biodiversity, which needs to be conserved, then it means human activities are minimized,” insists Musingwire.

Gorillas needed a quiet environment to flourish and reproduce. Regular contact with humans puts them at significant risk because of their genetic similarity, making them susceptible to diseases that affect humans.

“Humans share with gorillas over 98 percent genetic materials and can easily make each other sick,” reveals Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka, a wildlife veterinarian and founder of Conservation Through Public Health.

Conservation Triumphs

The conservation model used to conserve Nyungwe, and Gishwati rainforests in Rwanda has registered success at the expense of nobody. Likewise, the conservation model used to safeguard Bwindi Impenetrable Forest in Uganda is registering triumphs but an apparent cost to the indigenous Twa people.

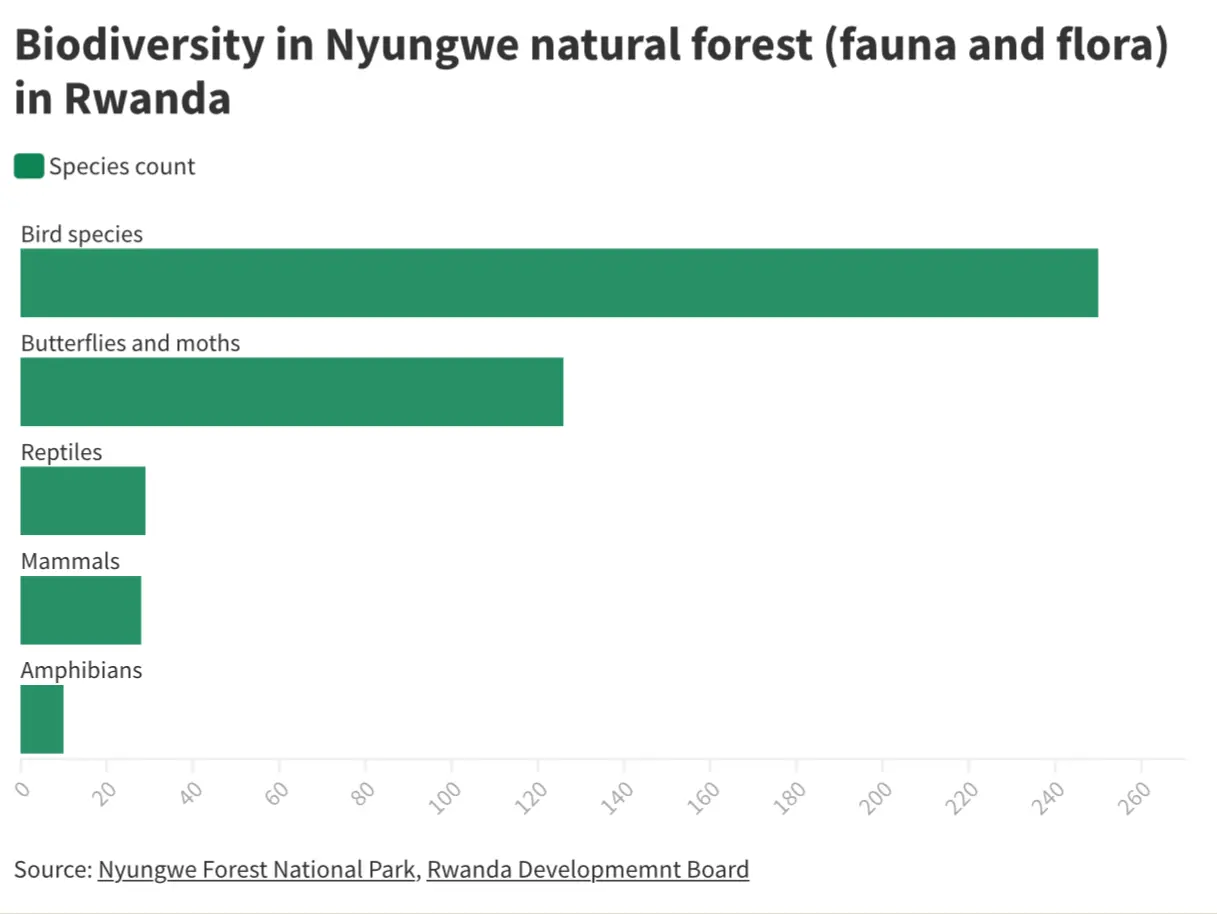

Mateso Sikubwabo, an indigenous community member and a former poacher in the Nyungwe rainforest in Rwanda, says much progress has been registered since 2004, with the park now a haven for 275 bird species, 1,068 plant species, 85 mammal species, 32 amphibians, and 38 reptile species.

For Gishwati, the forest that decreased from 28,000 hectares in the 1970s to about 600 hectares in 2002 is now a flourishing Biodiversity Resource.

The Gishwati Natural Forest is today home to animal species that are under international alarm for protection. According to Forest of Hope, these are eastern chimpanzees (listed as threatened on the IUCN Red List); golden monkeys (listed as Endangered); mountain monkeys (listed as Vulnerable); and more than 200 species of birds, including 16 that are endemic to the Albertine Rift and two IUCN Vulnerable species: Martial Eagle and Grey Crowned Crane.

“The ecosystem services that Gishwati Natural Forest generates are enormous. It has been estimated that the value of the carbon sequestered in the core forest of 886 hectares alone has the potential to contribute $3,000,000 per year to the Rwandan economy,” Hope of Forest further asserts, adding that the forest serves local farmers by absorbing and slowly releasing rainwater, preventing loss of topsoil, preventing sometimes-disastrous landslides, and stabilizing microclimate.

In Uganda, after almost 30 years of fortress conservation for the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, more plants, mammals, and birds are returning to the Bwindi impenetrable Forest. And the Mountain Gorillas are no longer critically endangered.

In 2018, the then critically endangered Mountain Gorillas were down-listed on the IUCN Red List to endangered species after their population increased from 680 in 2008 to 1004 in 2018. And more are being born.

“Ten gorilla babies were born in COVID-19 lockdown (March to June 2020),” narrates Bashir Hangi, the communications manager for Uganda Wildlife Authority, noting that “protection of gorillas is a matter of imperative.”

Dispossessed and damned lives

“We have no proof that the land we live on now is ours. We can be evicted again anytime,” narrates Gad Shemanjeeri, a Mutwa pygmy and executive director of Batwa development organisation in Echuya, Rubanda district.

Although there may be increasing numbers of mammals, birds, and tree species in the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest — as indeed there are several — the Batwa people, that were once part of this ecosystem, haven’t recovered from the effects of the loss of their lands. They are concerned they still own no land, are slowly losing their culture and knowledge systems, and living in abject poverty.

“We have no proof that the land we live on now is ours. We can be evicted again anytime,” narrates Gad Shemanjeeri, a Mutwa pygmy and executive director of Batwa development organisation in Echuya, Rubanda district.

The eviction from their ancestral lands has caused suffering in all measures — not to put it too expansive — to all 6,200 Batwa (2014 Uganda Population and Housing Census) in Uganda that now live on donated land in the margins of their ancestral forests, surviving on the charity of sympathizers. For most of them, hopelessness defines their lives.

“Removing indigenous people from their land is, unfortunately, a consequence of so-called fortress conservation whose time is long past,” Wendee Nicole, founder and director of Redemption Song Foundation.

Redemption Song Foundation supports Batwa in Bwindi.

“They (Batwa) can’t go in and gather materials to make baskets. They can’t get food like honey and medicinal plants,” laments Nicole.

Jonathan Baranga, professor of zoology and wildlife, also a former director of Uganda National Parks (now Uganda Wildlife Authority), is one of the officials who campaigned for raising the conservation status of the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest.

He recounts that before the elevation, “people were busy mining gold and wolfram within the area and cutting down trees for timber, which was damaging the habitats of gorillas.”

Stuart Maniraguha, the director for plantations development at National Forestry Authority, says the approach taken by the government of Uganda facilitated the creation of an environment for the gorillas to flourish, reproduce, and contribute to the restoration of the Bwindi impenetrable forest.

“Conserving gorillas in a way contributes to the conservation of the forest,” notes Maniraguha. He elaborates that “when trees are missing, the gorillas will not be there because you have deprived them of their home…, their food sources…, and their privacy, therefore they will not mate, and their reproduction will go down.”

Like in neighboring Rwanda, tropical countries, rainforests are subject to increased changes in Uganda. High population, industrialization, road construction, urbanization, commercial agriculture, and changing climate are shrinking the once-blooming forests.

For example, in the Hoima district, a sugar factory has been blamed for deforesting part of the Bugoma central forest reserve to grow sugarcane to produce sugar.

However, Bwindi Impenetrable Forest and some other protected forests have continued to bloom amidst such threats, according to Maniraguha.

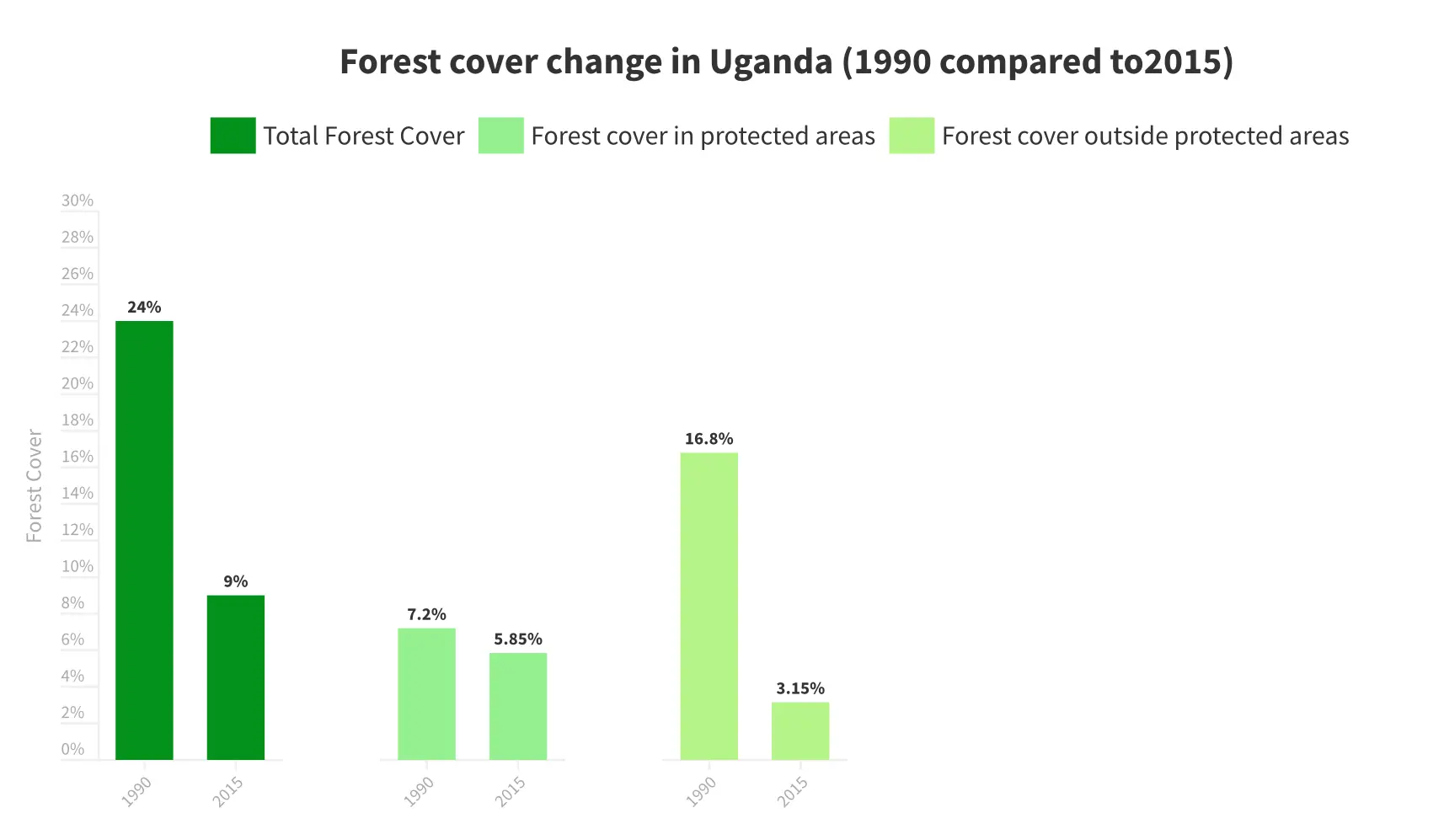

He states that in 1990, Uganda had a 24% forest cover, with protected forests accounting for 30% and the remaining 70% outside protected areas. And by 2015, Uganda’s forest cover had reduced to 9%.

But, “of the 9%, (in 2015) the area where we had 70 % (in 1991) had lost up to 35% (in 2015). Where we had 30% in the protected areas (in 1991) now the forest cover goes to 65% (in 2015),” notes Maniraguha.

Life In the Jungle

What if Uganda's Twas had remained in the forest?

Prof. Jonathan Baranga, the architect of the move to upgrade Bwindi Impenetrable Forest to a national park status, shudders at thinking about what would have happened if Bwindi Impenetrable Forest’s position had not been upgraded and Twas evicted.

“I know many government officials and businessmen were not only selectively cutting Mahogany (trees) from Bwindi and other areas, but there was a lot of encroachment. There was a lot of gold mining,” notes Prof. Baranga.

This is corroborated by a study that looked at regeneration in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park and found that before 1991, many large trees were cut for timber by pit-sawyers.

One of the persons that have lived close to the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest for over 80 years is Eliphaz Ahimbisibwe. He is aged 85 and lives in Buhoma, Bwindi. He says as part of the program for upgrading the status of Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, neighboring communities were in the 1990s taught to plant their trees, and now they do not need to cross into the woods for firewood and timber.

Without this option, Ahimbisibwe believes, “the forest would be no more because people would have cut it down and the gorillas would not be there because people had by the 1960s started hunting them for various products.”

But Amos Ngambeki, a father of four and a Mutwa of Buhoma in Bwindi, disagrees. He insists that amidst increased intrusion of the outside world into indigenous people’s communities and lives, Batwa people would still be guardians of the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, and the woods would flourish more than they are now.

Ngambeki notes that with their “rich indigenous knowledge of conserving forests,” coupled with “government empowerment,” Batwa would have been able to preserve Bwindi Impenetrable Forest for years to come.

The weight of the knowledge indigenous people possess is enough to maintain the ecosystems more naturally and sustainably, according to Bakole, who insists that Twa have experience in park management in their traditional ways. “For instance, during my pilot study conducted in Nkuringo in Bwindi, a Mutwa man declared that they are not allowed to hunt or trap pregnant animals and/or babies. Whenever they fall into our traps, we have to release them,” notes Bakole.

According to Bakole, this idea is backed up by another Mutwa he interviewed in the Mikeno sector in DR Congo as he collected data for his MA dissertation on Batwa.

Citing what he was told, Bakole reveals that “he said according to our culture, we cannot kill a gorilla because it resembles a human being, it resembles us.” Based on this statement and several others he got in the field, Bakole concludes that “the presence of Batwa in conservation matters because they understand well the dos and don’ts in biodiversity conservation.”

According to studies by the World Resources Institute, deforestation levels are “2.8 times lower in tenure-secure” indigenous people’s communities.

Several Twas in Uganda are losing the value of being called guardians of the rainforests. It is easy to understand why: modern society is imposing many hardships on them.

Take an example of Bakole’s latest research on Batwa of the Democratic Republic of Congo: one of the questions in this study wanted to determine whether the current socio-economic conditions could pull Batwa to support the conservation efforts.

“Out of 87 Batwa interviewed, 60 and above showed that they would never support conservation efforts because they are abandoned, marginalized, and sometimes arrested by rangers,” notes Bakole. He further quotes one of the interviewees, saying, “we are poor, we keep begging and picking leftovers in other communities’ gardens, and then how will I conserve the biodiversity?”

Building effective partnerships

Indigenous communities like the Batwa in Rwanda, DRC, and Uganda self-identify as having a link to surrounding natural resources. Conservation experts recommend their involvement to lessen human-conservation conflicts.

It is evident that the impoverished Batwa people in Uganda may turn into poachers of the resources they once protected — unless issues such as lack of land, repression over them, and the lack of involvement in the conservation efforts are fixed.

They are incapable of defending the forest — that was once their home and source of livelihood against illegal encroachments and damaging exploitation.

Although they know they cannot be allowed back into the rainforests, the Batwa people demand “resettlement; benefits from the presence of gorillas and the park and active involvement” to facilitate the conservation of the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest.

This can then be coupled with tapping and preserving their traditional ecological knowledge, marrying it with the modern experience for the management of rainforests.

Some scientists like Professor Beth Kaplin, the Director of the Center of Excellence in Biodiversity and Natural Resources Management of the University of Rwanda, believe it is crucial to find out what kind of activities communities could commit to.

“We need to take time to find out what kinds of activities communities want, need, and could commit to and steward in a sustainable way to come up with durable actions that address biodiversity conservation and climate change issues,” she says.

According to Vincent Munyengango, a local administrative leader from Bweyeye, a remote village in South West Rwanda, “These communities are major stakeholders in the management of forests since they enjoy immediate benefits of the forest products. They cannot allow any activity causing degradation of the ecosystem.”

Header image: A Twa youth walks on a fallen tree close to Bwindi impenetrable rainforest in Kanungu, Uganda. Credit: Fredrick Mugira.

Editor: Fredrick Mugira.

Reporters: Fredrick Mugira and Aimable Twahirwa.

Designer: Jonathan Kabugo and Fredrick Mugira.

This story was produced with support from the Rainforest Journalism Fund in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.