In the photo taken with his phone, Takakudjyti Kayapó holds a round-bellied silver matrinxã fish in front of his chest, the fingers of his left hand wrapped around the base of its tail and the fingers of his right securing its head.

He's sitting in the stern of a simple white aluminum motorboat, floating along the calm waters of the Curuaés, a river known to his people as the Pixaxá. It runs along the western edge of two Mebêngôkre Kayapó territories, located in the Brazilian Amazon state of Pará and providing a handful of villages on its edge with fish to eat, water to drink and a place to wash and bathe.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund journalism covering underreported issues around the world. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

That day in April, the Indigenous man, better known as Takakre, took to the river at dawn. As he glided along the tree-lined water, the air hot and damp despite the early hour, he asked a fellow resident of Mopkrore, the riverside village where he lives, to take the photo with the matrinxã.

Farther upstream, he took a selfie. A small jejú fish with a black stripe across its middle dangled from a line he held up to his face.

Once he returned home, he took more photos — one of his hands stretching a tape measure across the body of a piau fish lying on a wooden bench, another of the same spotted fish hanging from a hook on a digital scale under a thatched roof.

"Good morning to everyone in the group," he types into his phone. He's sending his photos and a spreadsheet he's filled out with all the details of his catch to a WhatsApp group called "Fishing Monitoring," with an emoji of a chubby blue fish next to the name. Another nine men monitoring fishing in their villages receive the message as do an interpreter, three technicians and a coordinator from the Kabu Institute, a nonprofit started in 2008 by the Mebêngôkre Kayapó and named after a leader in their mythology who used his arrows to tunnel through high hills in front of them, representing the overcoming of future obstacles.

Later, tissue samples from the fish will be tested for mercury, the heavy metal used by illegal miners to separate the gold they so desperately seek from other minerals.

The Mebêngôkre Kayapó worry that mercury could be contaminating the fish they eat. They want to better understand what effect mining — both on their land and just outside its borders — has on the aquatic populations they rely on for sustenance. They knew scientists had done studies to find out just that in other rivers and in other Indigenous territories. But they didn't want to wait for outsiders to discover what was happening on their own land.

So with funding from donations received through FUNBIO's Kayapó Fund, many from charities like Conservation International and the International Conservation Fund of Canada, they partnered with researchers and learned how to start a study of their own. They hope the evidence they've collected will enable them to better take care of their health and to prove that irreparable damage is being done to the forest where they live.

The damage caused by interlopers

One of 305 Indigenous groups in Brazil, the Mebêngôkre Kayapó, who number some 9,400 people, live on the largest tract of Indigenous territory in Brazil, roughly the same size as South Korea or Iceland. Their villages dot the Xingu River and its tributaries, sitting far south of the Amazon River in the states of Pará and Mato Grosso.

Their land, located in an area of the Amazon's southeast known as the "arc of deforestation," has remained relatively pristine compared to other Indigenous territories in the region. That's due to the swift expulsion of illegal miners, loggers, farmers and land grabbers who encroach on their borders.

But some of these interlopers still do damage before Mebêngôkre Kayapó warriors, who scour the forest on foot and by boat, manage to track them down and force them out. If they refuse to leave, they hold them in their villages until the federal police, the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) or the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) arrive to remove and charge them.

And sometimes what goes on just outside the perimeter of their territory can have an equally devastating effect within its borders.

That's what they learned from a study in Nov. 2018 conducted by the Federal Prosecutor's Office and the Federal University of Pará. The fish tested were from the Curuá, a river that runs west of the Pixaxá alongside the BR-163 highway before meeting the smaller body of water on Mebêngôkre Kayapó land, and the Baú, which flows to the east of the Pixaxá through the Indigenous territory.

Results showed that fish in both rivers had high concentrations of mercury in their systems, with some surpassing what the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (ANVISA) consider safe. According to WHO, overexposure to mercury can cause neurological and behavioral disorders. Symptoms range from headaches, insomnia and memory loss to tremors, neuromuscular effects, and cognitive and motor dysfunction.

Even the fish that didn't hit the mercury limit are dangerous to the Indigenous group, the report said, since the community members subsist largely on fish from the rivers, so mercury could accumulate in the body.

For the Mebêngôkre Kayapó living along the Pixaxá, the results from the Curuá were particularly concerning, since the two rivers meet on their territory and their headwaters are next to one another, just outside the land's border.

"There is a lot of mining activity on the Curuá River," says Luis Carlos Sampaio, a biologist who is responsible for organizing training at the Kabu Institute and coordinating the fish monitoring project. "So we wanted to find out how much the fish from the Pixaxá are affecting the Mebêngôkre Kayapó too."

Through the nonprofit, the Indigenous group developed a partnership with technicians at Unyleya Socioambiental, a company that helps communities find solutions for socio-environmental problems. With the company's support, the Mebêngôkre Kayapó selected two monitors from each of the five villages sitting on the southern portion of the Pixaxá that would carry out the study, both in the rainy season and the dry season, to make sure that all species and types of fish — carnivores, omnivores and herbivores — were included.

How they measure the mercury

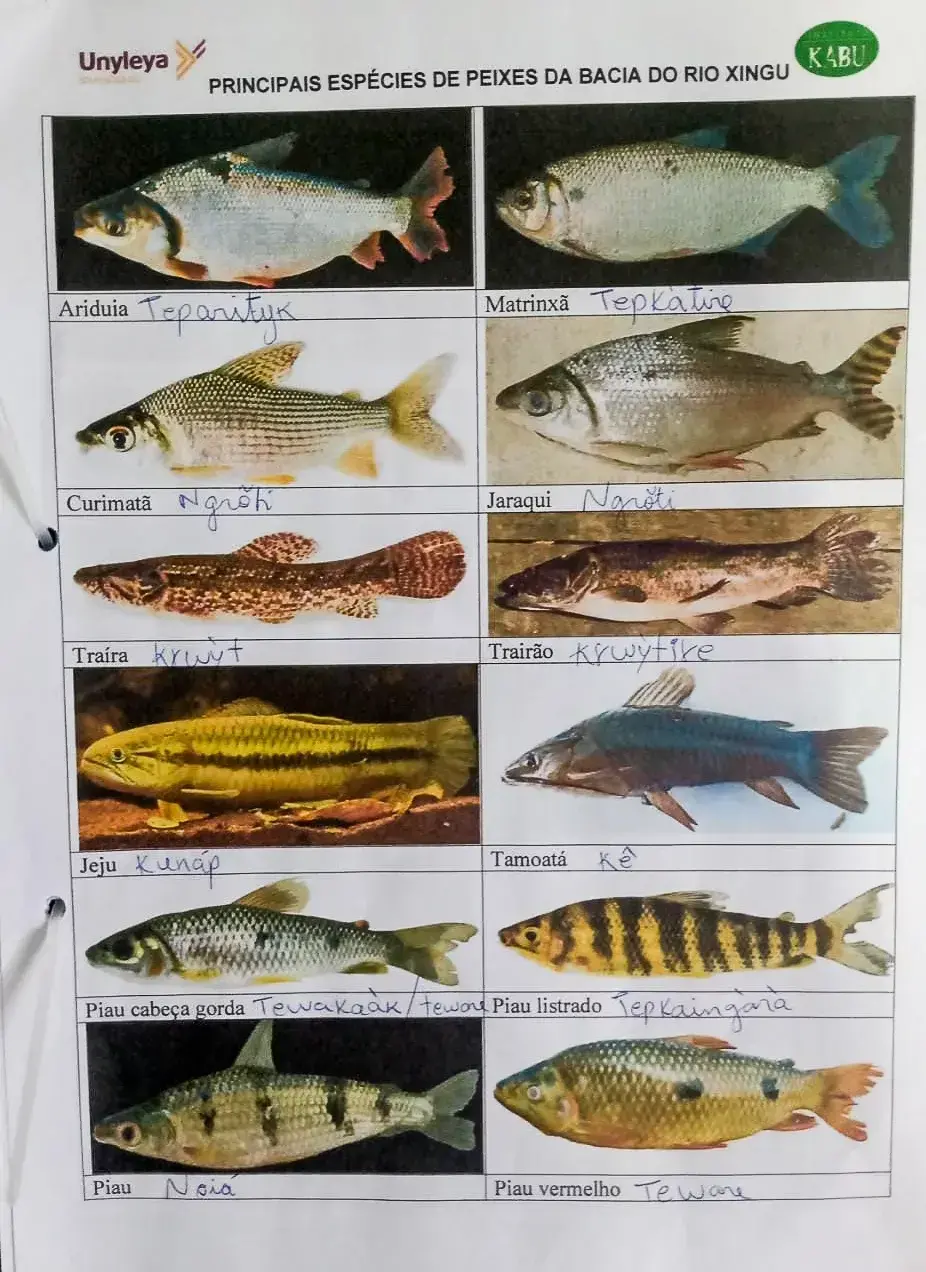

Takakre is one of those monitors. Along with the other nine selected for the job, he learned how to record data about the fish he and others in his villages catch — species, length and weight — as well as the time they set out to fish and the time they actually started, when they packed up for the day and when they arrived home.

"These types of information help measure how healthy the fish population is," says Alany Gonçalves, a biologist from Unyleya Socioambiental working on the Mebêngôkre Kayapó fish monitoring project. "If they have to go far to fish, if they're taking a long time to catch very little fish or the fish are small, or if they come back with no fish at all, that tells us a lot about what's going on in that river."

Taking the delicate tissue samples for mercury testing is a technical task requiring years of training. It's handled by technicians, like Gonçalves, who make periodic visits to Mebêngôkre Kayapó land. But because the scientists aren't always in the villages, it's the monitors who have the essential task of recording other fishing data every month and sharing it in their WhatsApp group, one of the most important tools for their study.

The chat app group helps bring the monitors together and feel like a team, despite not seeing each other on a daily basis. It gives them not only the ability to send in their findings and ask questions, but also the incentive of seeing how others are carrying out the same tasks in neighboring villages and talking about the best ways to keep the study moving forward.

The team from Unyleya Socioambiental made the 683-mile trip from their base to Mebêngôkre Kayapó land in early May to present the study's partial results to some 70 residents of the participating villages. Final results will be ready in early 2023.

Unfortunately, no surprises

The findings were exactly what they had expected.

From December 2021 to March 2022, the 10 monitors collected data on 813 fish from 28 different species. Of those, 29 fish, either carnivore or omnivore and from 10 different species, were tested for mercury. All tested positive and two — both carnivorous — were of particular concern.

One, a peacock bass, tested above the limit deemed acceptable by ANVISA. Another, a long-whiskered catfish known as a spotted surubim, had almost reached it.

For Bep Ojo Kaiapó, the study's interpreter, the results were disheartening but unsurprising. In his village, Pyngraitire, where the catfish was caught, having this new information means residents have been able to make more informed decisions about what they eat.

"Once we saw the results we started eating less of certain types of fish," says Bepté, as he is known. "If there's something we can do to avoid getting sick, then we'll do it."

For Takakre, knowing what's happening on his own territory, despite the worry, has given him a sense of relief. Now that he sees the members of his community using the information he collected to protect themselves, he knows how important his work has been and that it needs to continue. He wants as much information as possible for his people and hopes the project will be extended beyond the initial study with continued funding from FUNBIO's Kayapó Fund.

While the project has helped keep the community safer in the immediate, he wants to make sure it goes further, serving as evidence that can change policy to better protect their land and health.

"I do this for my children, for their future," he says. "Because they deserve better."