An English summary of this report is below. The original report, published in Portuguese in Folha de S.Paulo, follows.

A tour of some of the most remote corners of the Peruvian Amazon provides several lessons for the future

The eastern Amazon is home to the jungle blocks with the highest concentration of Indigenous groups in voluntary isolation on the planet; peoples who a century ago took refuge in the most inaccessible corners of the jungle, fleeing from slavery in rubber plantations. Since then, they have lived self-sufficiently, outside of the market economy, consumer goods, and the abstractions of the nation state; moving between Peru and Brazil along paths now invaded by drug traffickers, in lands encircled by illegal fishermen and coveted by loggers and miners. Despite all this, their territories remain among the best preserved in the basin and are a priority for climate, biodiversity, and global food security, the three great challenges of a decade that will determine the future of the planet.

For the majority of society, dependent on money, cell phones, and fossil fuels, the questions are many: How do the last isolated peoples of the Earth live? What is it like to share territory with them? How did those who established contact with the outside world a few decades ago fare?

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund coverage of Indigenous issues and communities. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

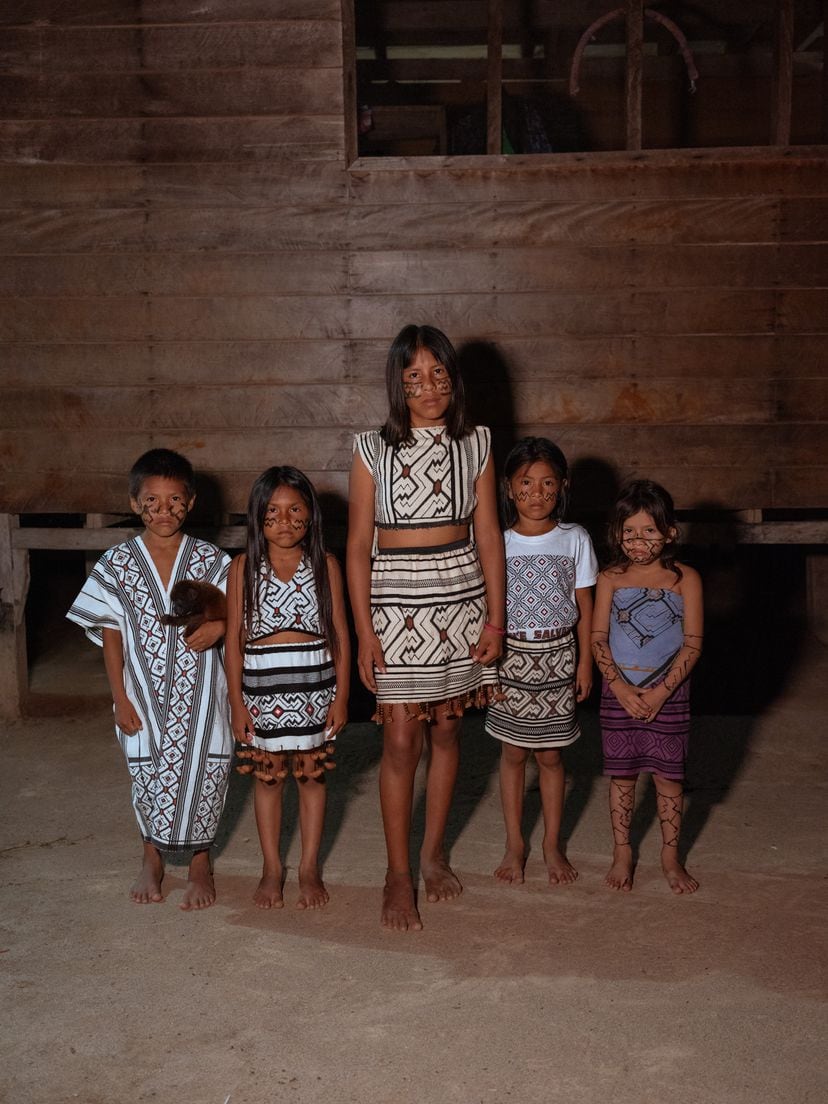

This newspaper has traveled to some of the most remote corners of the Peruvian Amazon to talk to the Indigenous Matsés, who came out of isolation in 1969, and to document the coexistence between a settlement of Yine settlers and the Mashco Piro: the former, grandchildren of slaves who killed the rubber boss and fled south; the latter, descendants of other speakers of the Yine language who would have chosen to go into the forest, becoming the largest isolated people in Peru.

This media has also traveled to the Amazonian city of Pucallpa to meet a new generation of Isconahua, a group forcibly contacted half a century ago and abandoned on the margins of society; without a voice in the decisions that affect them, but determined to change their fate. And threaded into these stories are Spanish researchers, a bishop from León, and Gustave Eiffel. Three Indigenous peoples, three stories, and many lessons for the future of the Amazon.

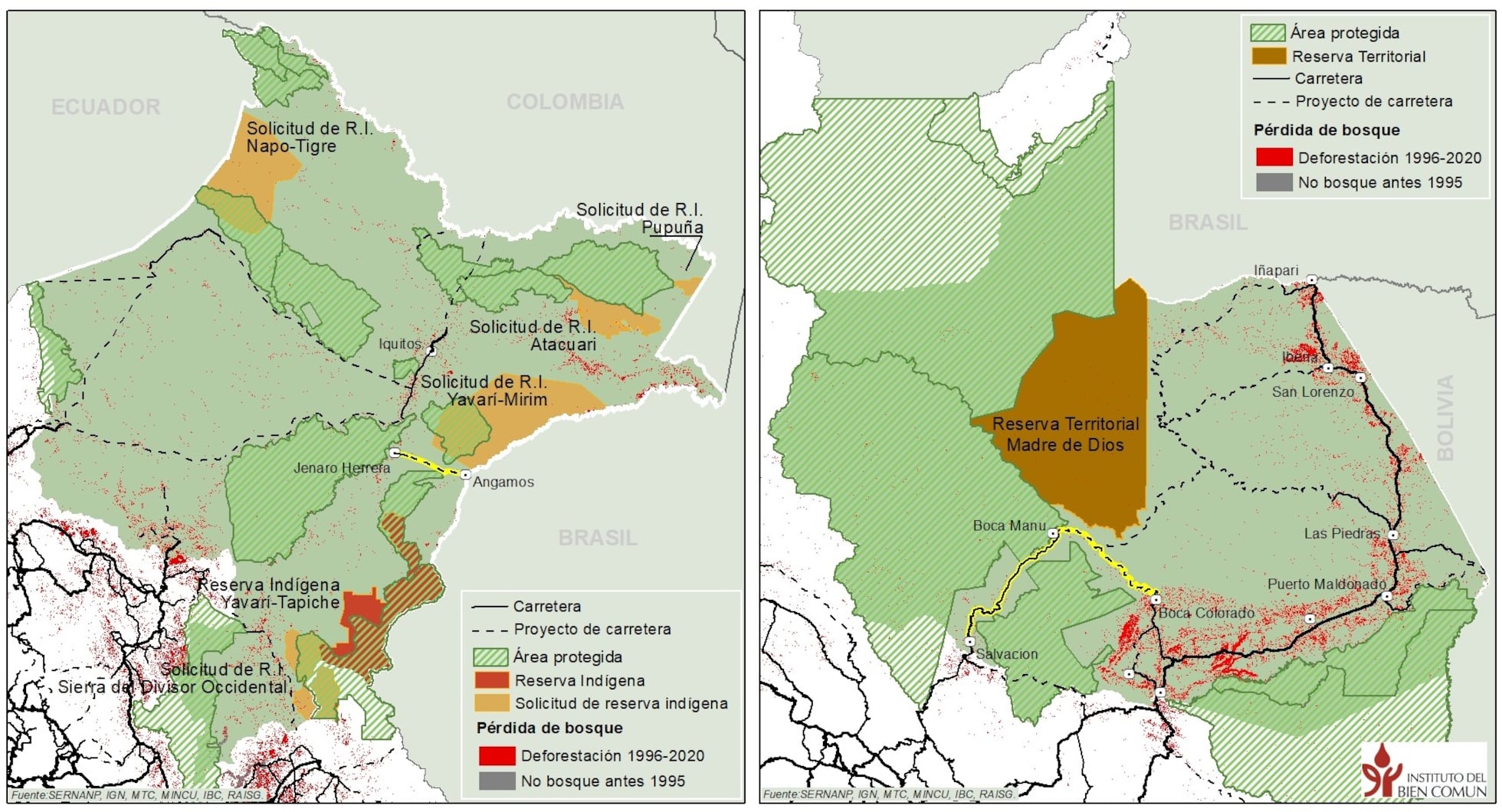

Figure 2: In the Madre de Dios region, a road inaugurated during the COVID-19 pandemic passes within half an hour's walk of one of the guard posts for the protection of isolated Indigenous people. Around this road, human and drug trafficking is proliferating. Infographic by Pedro Tipula, Institute for the Common Good.