The U.S. veto to export timber extracted from the Amazon to the United States hit them, but it did not stop them. The partners behind the two sanctioned companies reinvented themselves, with new companies and allies, to continue shipping wood, especially to the Dominican Republic and Mexico. There would be nothing special about this, except that this is not just any forest, but the largest oxygen reserve of the planet and that the Peruvian government doesn’t have the mechanisms in place to trace the wood from its origin.

A cross-border investigation by an international alliance of investigative journalists has uncovered how the owners of two of the first logging companies to be sanctioned by the US for selling illegal timber have continued exporting wood to several countries in Latin America. The investigation reveals how the Peruvian companies Inversiones La Oroza and Inversiones WCA redirected their exports to a number of countries, including Mexico and the Dominican Republic, leaving behind a paper trail riddled with inconsistencies.

These companies claim to verify the legality of their wood, but both neither have provided the U.S. and Peruvian authorities with any evidence showing they have improved their approach to tackling illegal logging, as the United States Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer confirmed when he ordered U.S. Customs to continue to block future timber imports from Inversiones La Oroza SRL (Oroza) on October 19, 2020.

USTR’s action was taken “based on illegally harvested timber found in its (La Oroza) supply chain” and because “the Government of Peru has not demonstrated to the satisfaction of the Timber Committee that Oroza is compliant with the necessary requirements for the harvest of and trade in timber products”.

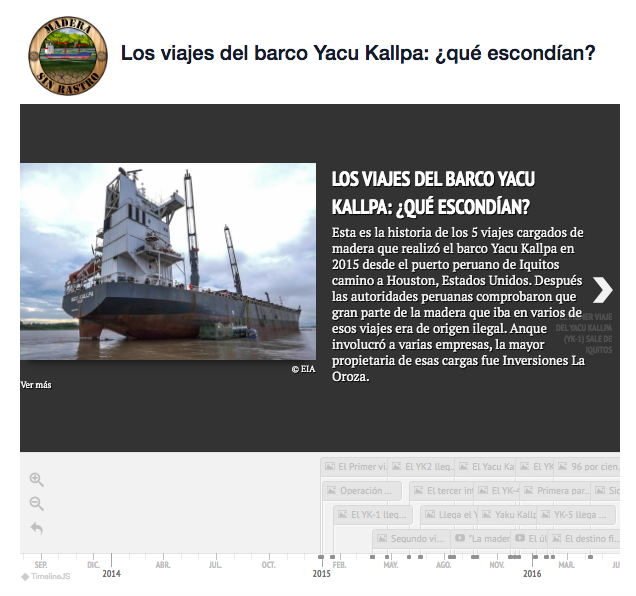

In 2015, Inversiones La Oroza was responsible for the largest shipment of illegal timber in the well-documented trips made by the ship Yacu Kallpa from Iquitos, in the Peruvian Amazon, to the United States. As a result, in 2017, a historic decision of the U.S. federal government banned the company from exporting timber to the country for three years, a sanction it renewed last year for another three, until 2023.

The second company, Inversiones WCA, E.I.R.L — responsible for the third largest cargo on the Yacu Kallpa — was banned from trading in the United States in 2019 after the Peruvian government found that a year earlier the company had shipped timber to the United States in contravention of Peruvian extraction and trade regulations. This year, U.S. federal authorities will decide whether or not to extend the ban.

This investigation found that both companies have continued to export to several other countries, including Mexico, where companies belonging to the logging conglomerate of the Ceballos Gallardo brothers continue to buy from them in spite of knowing that 97% of the wood exported in the Yacu Kallpa in 2015 (80% from La Oroza) came from illegal sources, as an investigation by the governmental agency Forest Resources Monitoring (OSINFOR) determined.

This collaboration sent several questions to the Ceballos brothers asking for their reasons to continue dealing with La Oroza and for the mechanisms they use to make sure the wood is legal, given La Oroza’s record. Ernesto Ceballos, the only one who responded, sent a short statement saying that his company “stopped importing wood from Peru because there are legal uncertainties with forest authorities in that country”. Ceballos didn’t say when they stopped imports from Peru or responded to any of the questions related to La Oroza.

La Oroza and WCA’s recent exports to countries other than the U.S. are not illegal, but the wood they commercialize, including endangered species, has been extracted from the Amazon during a period when both Peruvian and Brazilian authorities have dismantled or eased previous mechanisms of control to trace the wood from its origins, as this investigation also determined.

In Peru, several local Specialized Environmental Prosecutors (FEMA) have opened 52 cases against those involved in the Yacu Kallpa illegal exports, involving around 125 people and legal entities, including these companies, but investigations have been slow — partly because of the pandemic — and are yet to go to trial, according to two of the prosecutors.

According to Peru’s Public Defender of Peru’s Ministry of the Environment, Julio Cesar Guzman, Osinfor is no longer making field visits due to the pandemic. Osinfor’s previous president, Rolando Navarro, goes further and says those who “at some time wanted to discredit the operation that led to exposing the illegal exports on Yacu Kallpa’s shipments, are now working for the Osinfor”. Alejandro González-Zúñiga, previous manager of Serfor, Peru’s National Forestry and Wildlife Service, is convinced that something similar happened to Serfor.

Reporters asked both Osinfor and Serfor for comment regarding critiques to their oversight in recent times. Asked if supervisions and seizures were relaxed in the last three years, Serfor only responded that it carried out “some control actions» even during the pandemic and that between 2018 and 2021 it carried out 35 such actions on two species of cedar and one of mahogany listed on the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). However, it explained, «no seizures have been made».

An analysis of the Forestry Management Plans (FMPs) supervised by Osinfor between 2005 and 2020, by Peru’s Transparency International chapter, Proética, soon to be released to the public, found that 1301 of these FMPs have false information. For example, these plans allowed permit owners to legally log 758 thousand trees, but when they went to check, 132 thousand of these trees existed only on paper. In this way they could provide a legal cover to trees logged in unauthorized places.

It is no wonder that the World Bank estimates 80 percent of Peruvian timber exports are illegal and a recent analysis by the BVRio Institute, a Brazilian non-profit organization, estimated that more than 90% of timber products from the Brazilian Amazon may come from illegal operations or have some sort of illegality.

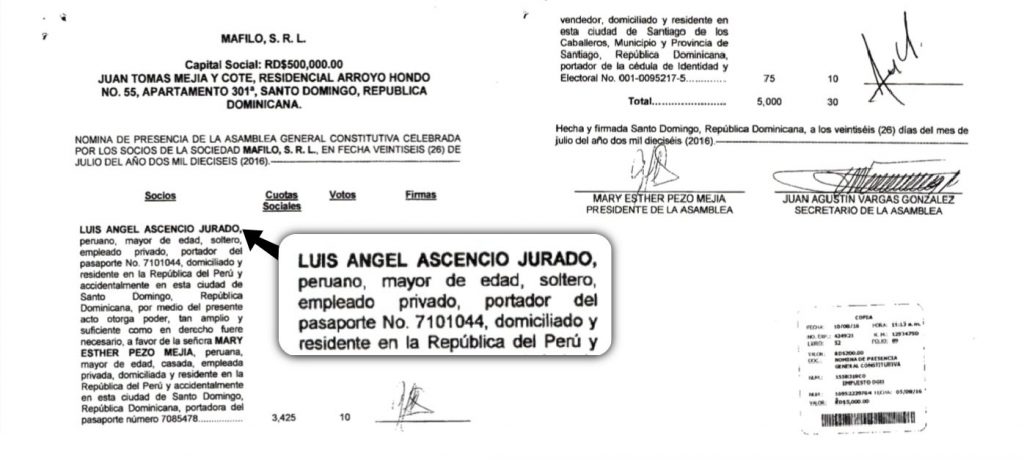

This investigation also discovered that Luis Ángel Ascencio Jurado, manager of Inversiones La Oroza, founded a company called Mafilo S.A. in the Dominican Republic — together with a Dominican partner — of which he is now its largest shareholder. Since its creation in 2016, this logging company has imported into the Dominican Republic US$5.5 million in timber from various countries, including Peru. In addition, it has imported several loads of timber of endangered Amazonian species from Brazil, purchased from two Brazilian companies currently under federal police investigation, suspected of having acquired timber whose origin was certified with fraudulent documents.

The Federal Police found these documents during a major investigation started in 2017 to stop illegal extraction of timber from the Amazon, called Operation Archimedes. Police sources said that since it has not yet finished the full report about its operations, it has not yet presented them to the Federal Public Prosecutor to consider for legal actions.

This journalistic alliance also found that after his company was sanctioned by the U.S. federal government, William Castro Amaringo, the main partner of WCA Investments, suspended timber exports with this company and continued exporting in 2020 with a different company of his, Miremi S.A.C., whose original business was sawing and planting wood.

This investigation also found that — in at least two sales from Peru to Mafilo — exporters reported higher prices in their country for the same cargoes declared in the Dominican Republic.

Interviewed in his headquarters in Iquitos, Luis Ascencio Jurado said that they make sure “that the origin [of the timber] is legal both in Peru and in other parts of the world,” and that since 2016 they take measures to extract timber from their own concessions and export it. “But statistically at the Peruvian level, our exports don’t even amount to 0.5% of all exported timber,” after the Yacu Kallpa case, their experts dropped by 80%." He also explained the reasons for the creation of Mafilo and his relationship to this and other companies.

The cross-border journalistic investigation, which analyzed data, official documents and specialized publications, and some thirty interviews and consultations with public officials, prosecutors, cargo operators, academics, ecologists, timber entrepreneurs and port agents from several countries, was carried out by Columbia Journalism Investigations (CJI), the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP), El Informe with Alicia Ortega of Grupo SIN (Dominican Republic), OjoPúblico in Peru, Mongabay Latam in Mexico and Peru, and Agencia Pública in Brazil.

New companies, old partners

Ascencio Jurado is a forestry engineer at the head of Inversiones La Oroza S.R.L. Ltda., a company he created in 2004 following his father’s trade, as he told reporters. Although the founding majority partner of Inversiones La Oroza was Ruth Antonia Ascencio Jurado, Luis Ángel’s sister, he holds the reins of the forestry company as its main owner and manager since 2019.

This company is dedicated to forest extraction, transformation and commercialization in the Peruvian regions of Loreto and Ucayali. According to OjoPúblico, a partner of this journalistic collaboration, it has been awarded five logging concessions in Loreto. Its headquarters are in the city of Iquitos and its wood yard is located in Pucallpa, Peru’s timber capital on the Ucayali River, where 87 sawmills operate, according to the most recent report from Peru’s National Forestry and Wildlife Service (Serfor). For years, before expanding abroad, the Ascencios supplied timber to one of Peru’s largest exporters, Maderera Bozovich.

In October 2017, the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) made the drastic decision to ban timber imports from Inversiones La Oroza for three years. It did so following a 2008 amendment to the Lacey Act, which makes it illegal to import illegally-sourced timber and allows authorities to require documentation of origin for any imports under suspicion of foul play.

The sanction was renewed in October 2020 for another three years, until 2023. “As of today, however, the government of Peru has not demonstrated (…) that La Oroza meets the necessary requirements to extract and sell wood products,” USTR’s latest statement on the matter noted in October 2020.

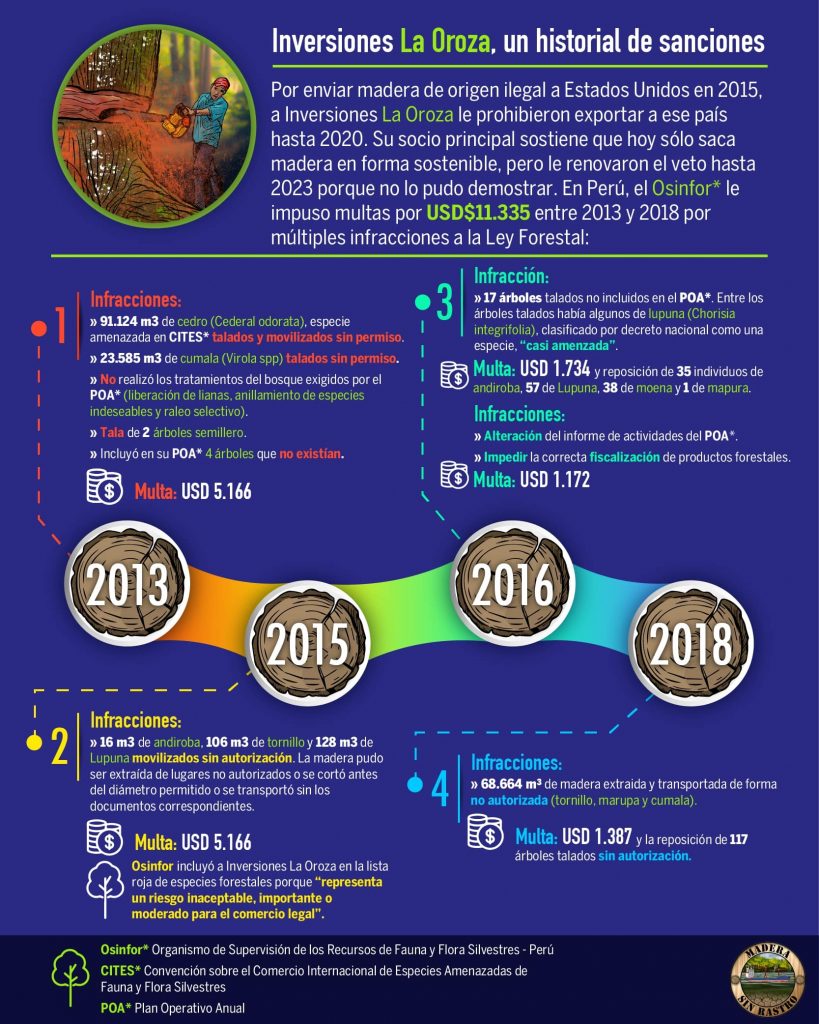

Between 2013 and 2018, La Oroza faced four inspection processes that found multiple irregularities for which it was fined a total of $11.335. Its infractions range from failing to comply with the forest management plans it committed to in two of its five concessions, extracting timber falsely covered by those plans and using transport forestry permits (GTF for the Spanish acronym) that do not match reality. (See infographic that details infractions and fines in Spanish).

In July 2016, just after the scandal of the illegal timber being exported on the Yacu Kallpa, but before the United States imposed its sanctions on Inversiones La Oroza, Ascencio created another logging company, Mafilo SRL, in the Dominican Republic with Dominicans Juan Agustín Vargas González (better known as John Vargas) and Amauris Andreu as minority partners. Andreu left the company and today only Vargas and Ascencio remain. According to the Dominican Republic’s Companies Register in Santo Domingo, Ascencio still holds the majority of the shares.

Vargas comes from a logging family in the Dominican city of Santiago de los Caballeros. Several years ago he split from the family business, Madesol, to set up his own trading company called Maderas del Valle (Madeva), his brother Arnaldo Vargas of Madesol told this team.

With Vargas as a common partner, the two Dominican companies, Madeva and Mafilo, work in tandem, as explained by forestry engineer Abraham Maca, legal representative of Inversiones La Oroza between 2015 and 2016. That was the time when the Yacu Kallpa was found to be carrying illegally-sourced timber obtained by La Oroza and the United States began its investigation. Maca was at Mafilo’s offices when this journalistic team contacted him. “If they have wood, he lends it to me, he gives it to us,” Maca said. “And it’s the same with me. It’s a friendly relationship, but nothing more. I call him ‘my partner’ because we talk to each other a lot, he helps me a lot”. However, contrary to Maca’s claims, official records show that Vargas is a partner at both companies, and Vargas himself explained his reasons for associating with Mafilo.

“The rationale for participating as a shareholder in Mafilo was expansion,” explained Juan Agustín Vargas in written answers to questions sent by this journalistic alliance. “We had the opportunity to be part of a company in the process of being formed by a long-time supplier of ours. At that time he was looking to tap into the Santo Domingo market, since Madeva SRL only operates in Santiago, except for specific requests from clients in Santo Domingo”.

Close partners

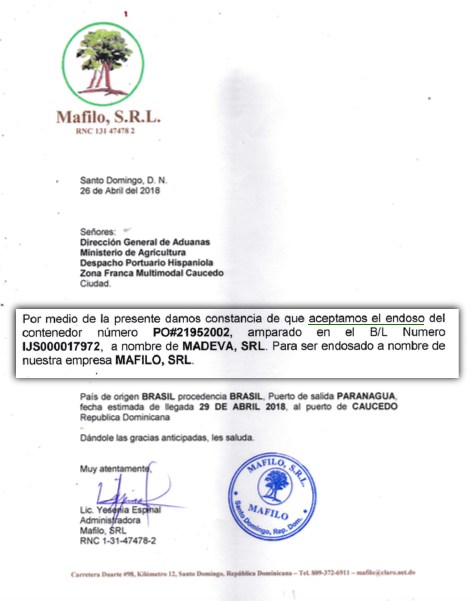

The following case shows how closely Madeva and Mafilo work. On April 29, 2018, Madeva imported 21,977 kilos of mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) from the port of Paranaguá in southern Brazil. Mahogany is a magnificent tree that grows up to 70 meters tall and is listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). By listing it on the CITES list, Brazil and Peru are informing the international market that this species is in danger of extinction and, therefore, its commercialization requires special verification that it comes from a sustainable forestry plan.

Significant mahogany forests remain only on the southern edge of the Amazon rainforest, from the Brazilian state of Pará to eastern Peru, according to a report submitted by scientists Mark Schulze of the University of Florida and James Grogan of Yale University to the International Tropical Timber Organization in 2013.

The Ministry of Environment of the Dominican Republic reported that importing companies wishing to bring in timber of CITES-listed species, such as certain species of cedar or mahogany, must obtain a permit from the Biodiversity Directorate of that ministry and present to it a “non-detriment finding” issued by the CITES authority of the country of origin. The Biodiversity Directorate confirmed that Madeva was indeed registered as the importer of the mahogany from Brazil, and therefore presumably submitted its CITES permit.

However, Madeva only served as a bridge for Mafilo SRL. According to detailed documentation from Brazilian customs, the former ceded the cargo to the latter, for an FOB value of US$29,454.

Inversiones La Oroza and Mafilo are also very close. When a journalist from this team asked Maca about how the complete chain of his company worked, he said:

“We have the sawmills, the concessions. But this is really a small market. The big market is Mexico, not the Dominican Republic. Almost everything produced in Peru goes to Mexico. The containers with the oak, the congona, do come here. But the big market is Mexico. We sell a lot there”.

In effect Dominican imports of sawn timber in 2019 were US$89.9 million, according to data from the Observatory of Economic Complexity. That same source reports that Mexican imports were US$531 million in that year. However, Dominican timber market is disproportionately large compared to the size of its economy.

“The company that we manage there with John”, explained Ascencio, referring to Mafilo, the company he has in partnership with Juan Agustín Vargas, “is a very different company, it is a company in which I have shares, minimal, but I do have them. We work with countries other than Peru, we work with American wood, African wood. We do not handle wood from here in South America. It is a completely separate matter from the one here”.

However, official documents say otherwise. First, Ascencio is in fact a majority shareholder of Mafilo. And secondly, since its creation, Mafilo has imported to the Dominican Republic almost 1,425 tons of wood for an FOB value of US$1,170,285 sent by Inversiones La Oroza from Peru, which represents one seventh of all its imports.

Confronted with the official records that show he has been Mafilo’s main shareholder since its creation, Ascencio ended up acknowledging his role as the main owner. “You can say I am the main shareholder, yes”.

Convenient partners

The expansion of Inversiones La Oroza does not end there. Just in the same month that the U.S. government’s trade authority demanded explanations from the Peruvian government regarding Inversiones La Oroza’s 2015 exports of illegally-sourced timber, the husband of an aunt of Ascencio Jurado created a new company to market wood.

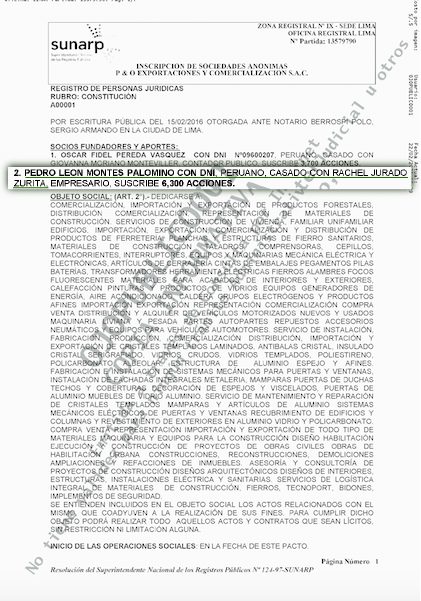

P&O Exportaciones y Comercialización was founded in Peru on February 15, 2016 by Pedro León Montes, as majority partner and owner of 6300 shares. Montes is married to Rachel Jurado Zurita, as recorded in the public registry. She is the sister of Luis Ascencio Jurado’s mother, Mila Jurado Zurita, as established by this collaboration.

This new company immediately began exporting timber, mainly from Inversiones La Oroza’s concessions, according to the Forestry Transport Permits (GTF) that cover the movement of timber in the Peruvian department of Ucayali. It also began opening markets and even exported 226 tons of Peruvian timber to the United States, according to official Peruvian customs records. No more exports of wood from this company to the United States were found after Inversiones La Oroza was sanctioned by the United States.

Luis Ascencio Jurado explains that P&O Exportaciones y Comercialización is a partner that buys timber from them for clients of their own that they have in the market. They have also allied with P&O, he added, “because in some way we get some tax benefit by selling wood to a company in the capital”. He specified that this is a tax credit on the General Sales Tax (IGV), a bonus given in Peru to companies in the provinces.

P&O Exportaciones y Comercialización also trades with the Dominican timber company Madeva, which was founded by Juan Agustín Vargas, Ascencio’s partner in Mafilo. Of a total of 7,296 tons of timber that P&O exported from Peru between 2016 and 2020, 66% went to two clients: Mafilo and Madeva.

P&O ships timber to Mexico and sometimes shares customers with Inversiones La Oroza. The latter continues to export to Mexican companies belonging to the Ceballos Gallardo family network. These are the same ones that had alleged their good faith when in 2015, in the Mexican port of Tampico, authorities seized a cargo of illegally extracted timber that they had bought from La Oroza, the sanctioned Peruvian logging company, and that La Oroza had sent to them on the Yacu Kallpa.

A prosecutor from the Peruvian Environmental Prosecutor’s Office (FEMA) had asked the Mexican authorities to seize the timber because it had already been established in Peru that the supporting documentation was riddled with inconsistencies. But, as was documented by the non-governmental organizations Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) and Global Witness the Mexican loggers who owned the timber and the Peruvians, through the embassy, exerted so much pressure that the timber was finally returned to the buyers, without even informing the FEMA prosecutor. Global Witness even published videos showing William Castro (owner of Inversiones WCA, one of the companies exporting wood of illegal origin on board Yacu Kallpa) talking about an agreement with a local Peruvian politician to liberate the wood in Mexico.

This cross-border collaboration established that, despite the scandal, the Ceballos Gallardo timber emporium remains loyal to Inversiones La Oroza, regardless of the fact that the latter continues to have sanctions in place in the United States. Mexico doesn’t impose sanctions as the U.S. does, but the trade agreement between the two countries and Canada would allow the U.S. to request information on Mexican wood imports.

In addition, it found that other Mexican companies that were previously customers of the sanctioned Peruvian logging company are now importing timber from P&O. In Mexico, importers are not required by law to verify that timber entering the country is legally sourced. Someone importing wood from Peru to Mexico has only to present the invoice, the phytosanitary certificate — a document that guarantees that the wood is free of pests and that, in theory, assures the legal origin of the wood, the CITES certificate, in case it is a protected species — and the customs declaration.

In this way, the two companies, Inversiones La Oroza and P&O Exportaciones, concentrated the bulk of their exports one in each country, and with close partners.

In the Dominican Republic, according to forestry engineer Maca, Mafilo, which was founded five years ago, is a small player in the timber world. Indeed, this investigation found that other timber traders in the country, such as Madesol, import much more timber than Mafilo. But even then, Mafilo’s is not a negligible operation: between January 2016 and February 2021, it has moved 7,255 tons of wood from Peru, Brazil, Spain, Ivory Coast and Cameroon, for a FOB value of US$5.5 million, according to figures from the Dominican Republic’s General Directorate of Customs.

In 2020, despite mobility restrictions due to the pandemic, Mafilo imported just over US$1 million from Peru. Of this only a small amount came from Inversiones La Oroza ($88,676) and considerably more from P&O Exportaciones y Comercialización ($488,343), according to data from the Dominican Republic’s General Directorate of Customs. Juan Agustín Vargas, co-owner of Mafilo with Luis Ascencio Jurado, in written communication to this team offered slightly lower figures: US$63,569 from La Oroza and US$487,491 from P&O.

The matter is noteworthy because in an interview with Ascencio Jurado, the businessman vehemently assured that Inversiones La Oroza had not exported timber to the Dominican Republic in 2020. He repeatedly challenged reporters to provide an example and even after they provided one, he continued denying the transactions.

Ascencio also insisted that the operation model he set up after being sanctioned in the United States, involving his alliance in Peru with P&O Exportaciones y Comercialización, the company of his relative, and the creation of Mafilo in the Dominican Republic, has no “‘ill will’, in quotation marks; it is a business, a small business that is all”. He reiterated that his only link with P&O is there for tax advantages and that Mafilo is a separate company that does not import timber from the area of Peru where he extracts it.

Two companies with suspicious records

On July 24, 2019, a shipment with 50 tons of cerejeira (Amburana cearensis) departed from the jungle city of Porto Velho, in the Brazilian Amazon. This wood, known in Peru as ishpingo and elsewhere as Brazilian oak, is on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) list of threatened species, under the intermediate category of “endangered”, on a scale where the most serious risk is classified as “critical” and the slightest as “vulnerable”.

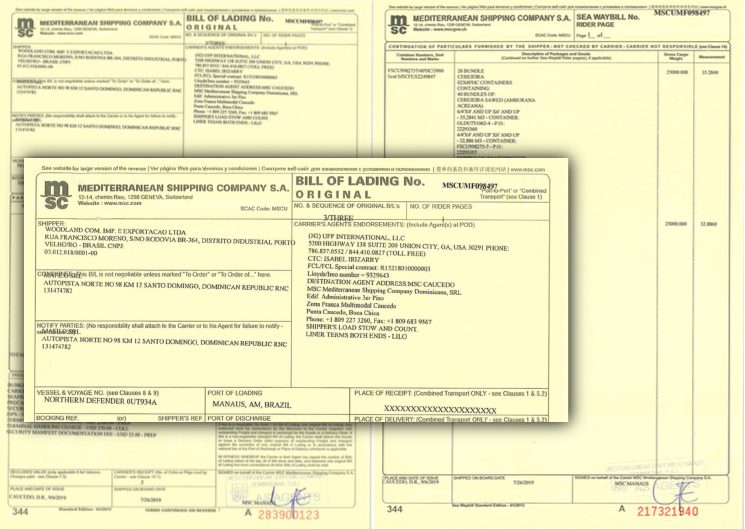

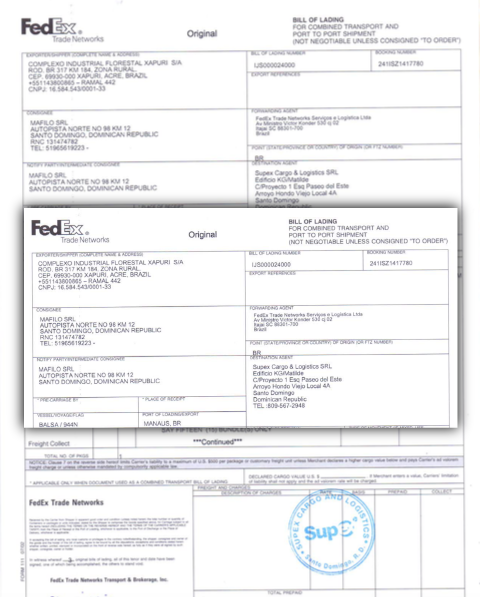

The cargo, which was bound for the Dominican Republic, had been exported by the Brazilian company Woodland Comercio Importaçao e Exportaçao, Ltda. On the ship’s customs manifest, the company Mafilo SRL was registered as the buyer in the Dominican Republic.

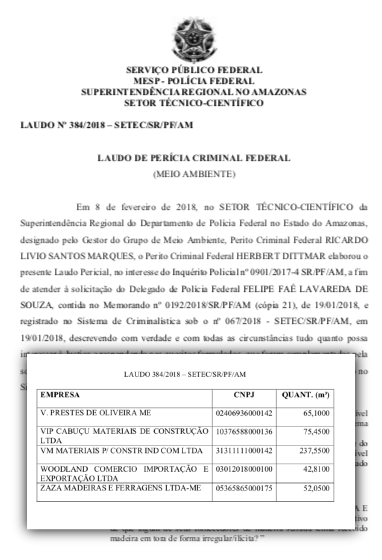

Woodland has been suspected in the past of buying illegally-sourced timber in Brazil. In December 2017, eleven Woodland containers were confiscated by the Brazilian Federal Police in the first major seizure of Operation Archimedes, the large-scale investigation with which Brazilian authorities sought to stop extraction of timber from the Amazon rainforest without authorization. In technical report 384 of 2018 the Federal Police points out that Woodland received 42.8 cubic meters of wood from Madeireira São Lucas, which, in turn, had mobilized 1,564 cubic meters (a volume that would fill approximately 51 trucks) gathered by logging native species in an area considered public.

This logging company was authorized by a logging plan approved by the Environmental Secretariat of the State of Amazonas, as required by law, but this plan authorized the extraction of timber from a different area to the one they were actually extracting it from. In report 333, the Federal Police also found that again in 2018, Woodland had purchased another 48.73 cubic meters of timber from the company Real Madeiras, also backed by a fraudulent logging plan.

On November 5, 2019, Woodland made another export of cerejeira or ishpingo from Brazil to Mafilo in the Dominican Republic.

When asked, Woodland’s lawyer and spokesperson before the Federal Police investigation, Maguis Umberto, said that the containers seized in Operation Archimedes have already been returned to the company following a court order.

The spokesman also said that they have delivered to the Federal Police the documentation that proves the legality of the chain of custody of the confiscated shipment, and that they are not aware of the irregularities pointed out in the documents of origin of the wood, but that the investigation is not yet finished.

Another similar shipment of the same type of wood traveled to the same destination, but this time exported by another Brazilian company, Complexo Industrial Florestal Xapuri, located in the Amazonian state of Acre.

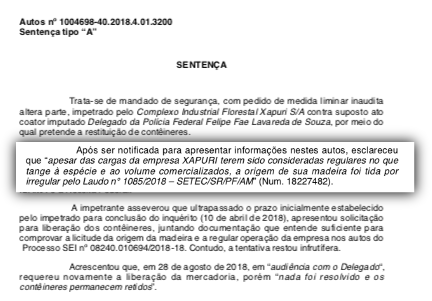

This company had also lost five containers in December 2017, confiscated during Operation Archimedes. According to the police finding, Complexo Industrial had purchased timber without proven legal origin from other logging companies and, along with Woodland, remains under investigation by Brazilian federal police.

When asked, the press office of Complexo Industrial Florestal Xapuri said that the five containers confiscated in Operation Archimedes had already been returned to the company by order of the federal court in Amazonas.

Neither company has been charged with any crime, the Federal Police has not yet hand over its findings to the Federal Public Prosecutor.

Both companies, furthermore, were mentioned in a different Operation Sinapse, of the Brazilian environmental police, Ibama, under similar circumstances, for having purchased timber of illegal origin from third parties.

For his part, Ascencio Jurado said that he did not know the Brazilian exporters who had sold the wood to Mafilo, since it was the logistics companies that found the exporters and financed the operation. Fedex Trade Networks was in charge of this operation. Consulted in Brazil, Fedex’s spokesperson said that the company has operated in Brazil since 2009, coordinating the logistics of shipping cargo by air and sea and that its services include reserving space in cargo containers to serve exporters and importers. “Exporters are responsible for complying with the requirements and providing the required documents to the authorities before the movement of exports from Brazil is approved,” he explained.

Some discrepancies

In contrasting the exports of Inversiones La Oroza and P&O Exportaciones y Comercialización to the Dominican Republic against what Dominican customs reported as imports from those companies from 2016 to January 2021, some inconsistencies appeared.

According to the official documents on file, in at least two shipments between 2017 and 2020 the Peruvian exporters reported higher FOB values (‘free on board’, which refers to the cost of the timber including port charges, labeling, packaging and customs fees, among others) for the timber than those reported by the importer Mafilo to the Dominican authority. The shipments, nevertheless, matched exactly in weight and type of wood.

For example, on November 21, 2018, Inversiones La Oroza exported two containers with 55,870 kilos of ishpingo wood from Peru to the Dominican Republic. The wood entered on December 4, with the exact same weights and container numbers - HLXU8531319 and BEAU4708612 - being reported as leaving Peru on the ship Callao Express.

In Peru, La Oroza reported the shipment with an FOB value of US$49,701, but the official import declaration provided by Customs in the Dominican Republic shows a lower price: US$28,280.

At the closing of the story, La Oroza sent this team an invoice for 20,6662.16 listing 35711 units of ishpingo sawn timber which, according to the company, makes up the difference in export prices. The invoice provided does not appear in the official records of the Dominican Customs.

Although the differences in the two Peruvian exports destined for Mafilo amount to only $32.000 more than what was declared by their corresponding imports in the Dominican Republic, the matter is important. According to Peruvian customs and trading expert lawyer Laureano López, if differences are confirmed in these export and import reports it could mean “something is not right”. “It could be that the importer is underpricing to pay less taxes, and normally the Peruvian exporter overprices to get tax reimbursements. If a crime is proved, for the Peruvian exporter it would be rent defrauding”.

This investigative team sent questions to P&O Exportaciones regarding these discrepancies. Its manager, Orlando Vega Japay, denied there were any price differences and provided a spreadsheet detailing invoices that match the original prices for all the cases this team had found. Vega sent some of the original invoices that, according to him, complete the shipments amounts.

The contrast analysis also found that tariff codes were changed with some frequency. For example, timber exported by Peruvian companies under code 4407.22, which refers to virola (Virola calophylla), imbuia (Ocotea porosa, listed as vulnerable on the global endangered species list) or balsa (Ochroma pyramidale) is reclassified upon arrival in the Dominican Republic under code 4407.99, a more generic code used for “other tropical timber”. At least 17 shipments, totaling 144 tons of wood imported from Peru by Mafilo, show this change.

When asked about this, Ascencio from La Oroza said this was not something he knew about or was responsible for.

In his recent analysis of discrepancies in the international trade of timber leaving Peru, researcher Camilo Pardo-Herrera found similar general patterns.

Cross-checking export data from Peru with import data from the countries to which Peru exported, for the same time periods and the same types of timber by tariff codes, Pardo-Herrera found that they do not match. Thus, for example, when he compared the statistics for Peru and Mexico, he found that Peru says it exported, between 2009 and 2018, on average, $4.1 million per year less than what Mexico reports having imported from Peru. And when he cross-referenced the Dominican Republic with Peru, he found that the reverse is true: for example, in 2015 Peru said it exported $2.7 million more than what the Dominican Republic says it has imported. All the data used by Pardo-Herrera has the same source: trade officially declared by countries to the United Nations and hosted by the UN Comtrade platform.

The WCA Investments turnaround

The other Peruvian company blocked by U.S. authorities from entering the country, from 2019 to 2021, is Inversiones WCA.

The order was given by then-U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer to the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agency in July 2019, as a result of a request made by the Committee on Trade in Wood Products to Peru in February 2018 to verify whether two shipments from Peru to the United States were complying with Peru’s environmental and forestry regulations.

“The request was made in the context of ongoing concerns that illegal logging continues in Peru,” said the statement announcing the sanction. After the Peruvian government conducted the verification, it found that a shipment of timber from Inversiones WCA had not been extracted in compliance with regulations.

This was the second time the U.S. government took strong action to enforce the forestry annex approved under the trade agreement between the two countries (PTPA).

Although the Peruvian government did not take specific measures to ensure that Inversiones WCA was extracting Amazonian timber in a sustainable manner, the company stopped exporting its products the year following the sanction, according to information from Peru’s customs.

However, its main shareholder, William Castro Amaringo — whose initials give Inversiones WCA its name — is also a partner in other companies in the industry, such as Consorcio Forestal de Loreto S.A.C., W&A Forest Company S.A.C. and Miremi S.A.C.

This investigation confirmed that Miremi did continue to export to Mexico, France, Denmark and China, all of them legit transactions because the company doesn’t have sanctions in those countries. Between 2019 and 2020, this company exported 4116 tons of timber worth $4.6 million, according to the Panjiva trade database. Its main clients are in Mexico, including a company in the Ceballos timber consortium. It is also noteworthy that the vast majority of the timber exported is of the Dipteryx odorata species, known locally and commercially as shihuahuaco or cumaru.

Although it is not currently protected by the CITES convention or on the IUCN red list of species, Peruvian scientists have been arguing for more than five years that massive exploitation of the very slow-growing Dipteryx odorata is putting species in danger of extinction. For this reason they are urgently calling for measures to protect it, such as inclusion on these lists.

This investigation team contacted Castro Aramigo to ask him why he had continued to export without having certified that his logging operation was in compliance with Peruvian forestry laws and regulations.

The businessman pointed the finger at the country’s authorities — Serfor and Osinfor — because, according to him, they were responsible for verifying the accusation but did not “work to move the forestry industry forward”, and this had harmed them. “So, we ended up with an unfair sanction. It has been three years that I can’t bring timber into the United States and nothing happens to the real informal loggers,” he said.

Death by commercial voracity

More and more countries are trying to regulate and control the international timber trade, particularly that of endangered species.

In addition to the aforementioned 2008 Lacey Act amendment in the United States that prevents the import of illegally-sourced timber and allows for requiring documentation of origin for any imports under suspicion of foul play, Australia issued the Australian Illegal Logging Prohibition Act in 2012 (AILPA) and the European Union brought out the EU Timber Regulation (EUTR) in 2013.

However, compliance with these laws and policies is entangled in increasingly complex supply chains.

Researchers agree that in both Brazil and Peru authorities have not had the capacity to regulate the voracious, unregulated and often illegal exploitation of the most commercial forest species.

An analysis of 2015 exports registered by the Callao port checkpoint of the Technical Forestry and Wildlife Administration (ATFFS) of the Peruvian Forestry Service, carried out by the environmental NGO Agencia de Investigación Ambiental, found that just 16% of the timber in the verified shipments turned out to be of legal origin. Another 17% was found to be illegally harvested and the remaining 67% “has a high or medium risk of being illegal”. Since then, as this investigation has reported, control and supervision has only weakened in Peru.

In other words, five out of every six trees could have been illegally extracted.

In another research paper published in the Journal for Nature Conservation, five Brazilian scientists from the Federal Fluminense University and the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden cross-referenced data from forest origin documents (DOF) between 2012 and 2016 with Brazil’s red book of endangered species. They found that, among the 2214 species traded, there were 38 endangered ones, totaling 6 million cubic meters. That was equivalent to 10% of all timber traffic in Brazil in that period. Some of these endangered species were among the 20 most sold species each year.

Logging that does not comply with sustainable forest exploitation plans contributes to the loss of Amazonian ecosystems, whose conservation is the greatest contribution of its countries to mitigating the climate crisis. For this reason, businessmen must ensure that the timber they sell comes from sustainable forestry, a requirement in Peruvian and Brazilian law, as well as that of the United States, Australia and Europe.

“But even orderly management does not guarantee sustainability,” ecologist Ángela Parrado Rosselli, who has researched the regeneration of species in the Colombian Amazon, told this journalistic alliance. This is not guaranteed because there is no clear knowledge of how many of these species reproduce, depending on the region where they are located, the quality of the soil and water, or the production of their fruits. “So governments apply generic norms that do not necessarily guarantee the regeneration of all species,” she explains.

In addition, says Parrado Rosselli, even when logging requirements are met, it is also essential to verify whether the forest was managed to allow the regeneration of weaker species.

Good forest management that can produce Amazonian timber at the industrial rates demanded by the world is therefore, at best, problematic. And as this journalistic investigation shows, even banned or suspect actors in the industry are difficult to track, as well as the wood from endangered species itself, given the many inconsistencies in international trade supply chains.

With an intensive and poorly regulated exploitation, Peru has lost 278,000 hectares of natural forests, mostly in the Amazon, in 2020 alone. And this is hardly surprising. According to the latest report by Global Forest Watch, those hectares now no longer drain 132 million tons of CO2 emissions.

Luis Ascencio Jurado, from Inversiones La Oroza, is convinced that it is not people like him, who exploit it commercially, who are destroying the Amazon. “I am still in this business because I am a forester first and foremost, and it makes me very sad that unscrupulous people are messing with our tropical forests and deforesting them in a criminal way,” he says, citing drug traffickers among those predators. “Everyone getting into this is making more and more money, to the point that in Iquitos there are coca crops already.”

He does not want to abandon those who have been working for his company for years, he explains, and although he is no longer exporting as much as he used to, he wants to continue trying. If he does not succeed, he concludes, he will have to leave the business.

For its part, Brazil is the country in the world that lost the most primary forest during the pandemic year, according to Global Forest Watch: 25% more than in 2019. Scientists agree that the 1.7 million hectares recently destroyed and the accelerated pace of devastation threaten to release millions of tons of carbon into the atmosphere and turn the Amazon into a savannah of devastated species.

Despite sanctions and international pressure to curb the exploitation of the Amazon, without proper controls in the countries of origin, timber traded by forestry companies, even those sanctioned, continues to flow to the world. They use new avenues and new partners, but the timber they export remains under suspicion about its true origin. The lack of clarity also prevents the destruction of this vital forest for humanity from being stopped.

- View this story on Ojo Público