A project by Robert Carrubba and Cintia Garai/Wildlife Messengers. Photography by Robert Carrubba.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund journalism covering underreported issues around the world. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Narration

The Kahuzi-Biega National Park, located in the South Kivu Province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, was established in 1970, and became a World Heritage Site in 1980. It is managed by the Congolese Nature Conservation Institute, ICCN, which trains and employs eco-guards to care for the park. This film is a look at the men and women who make great sacrifices to protect something that most of us will never see, but from which all of us benefit.

Many important and endemic characteristic species live here, including the critically endangered Eastern lowland gorilla, also known as the Grauer’s gorilla. Due to displacements during the Rwandan genocide, the First and Second Congo Wars from 1996 to 2003 and years of civil unrest, increasing human population in the region resulting in habitat loss and hunting, in 1997 the park was put on the ‘in danger’ list of World Heritage Sites. The Grauer’s gorilla was then thought to have been reduced from an estimated 16,900 individuals in the mid 1990s to only 3,800 individuals by 2016. In fact, the situation seems to be slightly better: According to a recent population estimate there could be 6,800 Grauer’s gorillas. The increased estimate should not change, however, the critically endangered status of this subspecies. Ensuring the survival of these gorillas is one of the major challenges that come with the complex job that the ICCN eco-guards do every day.

Bakongo Lushombo Antoine (Eco-guard)

"What I like is to protect my gorillas properly. I like to protect my gorillas properly. Because if the gorillas didn’t exist, there wouldn’t be any work. Any work. If things can get better here it is because of these gorillas."

Juvénal Munganga (Visitors Delegate and Tourist Guide)

"The gorillas that we have in Kahuzi-Biega, as a totally endemic (sub-) species, cause a lot of people want to visit the park. The gorillas really help the park come into contact with the outside world."

Jean Paul Kamuteba (Eco-guard)

"Sometimes a gorilla gets upset if he is not habituated to people yet, but with time we get him used to us."

Patrick Musikami (Chief of Research and Biomonitoring Program)

"We have to follow all the gorilla families. We must ensure that all families are healthy. And if a problem arises with a gorilla, we have to organize field trips to make an intervention, and we also need to report the issue."

Narration

Kahuzi-Biega National Park is the first site where gorillas were habituated to human presence for tourism. Before the wars, the park was once a tourist paradise. Habituating gorillas for tourism is an arduous process, which can take up to 4 years, and it is not without dangers for both the gorillas and the eco-guards. Tragically, many gorillas were killed during the years of war, including all the habituated silverbacks, because they were not afraid of humans. Today there are only a few habituated gorilla families in the park, but 14 non-habituated families are followed on a daily basis for protection and data collection.

Patrick Musikami (Chief of Research and Biomonitoring Program)

"The objective of the research and biomonitoring program is to improve the management of the park based on the results of research and biomonitoring. So the research and biomonitoring program is the pillar of the park, the data that we collect in the field are analyzed in order to guide the management of the park."

Jean-Baptiste Kadega Mwenza (Eco-guard)

"This is what gorillas eat in this season. Allophylus kivuensis is the scientific name of this plant."

Narration

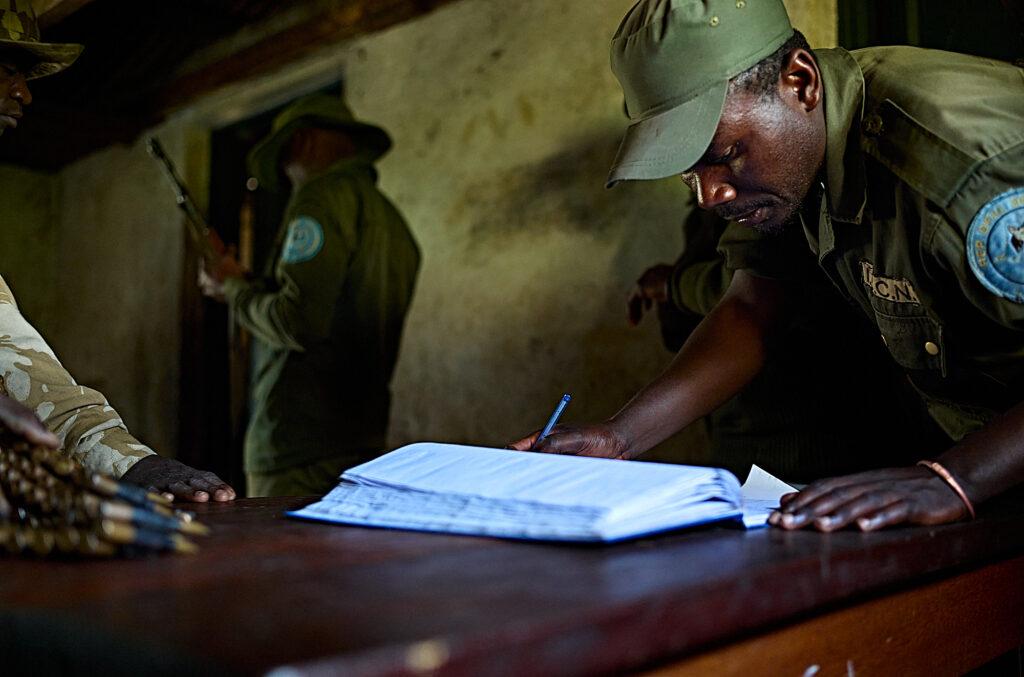

During patrols, eco-guards, following a strict protocol, secure the area, collect data on fauna and flora, and on illegal activities. They remove snares, which can seriously injure gorillas.

Narration

ICCN is evaluating the potential habituation of 1 or 2 new gorilla families. Eco-guards must carefully select among the potential families. Their decision depends on many factors, such as group size and composition, access to the range, and security of the region.

Innocent Mburanumwe (Assistant Site Director)

"We are exactly in the gorilla’s nest.

We can see that it was the chief (silverback) who spent the night here because only the chief has silver hair.

Let’s have a look at the feces. It is normal, so we can tell that this family is healthy. Why do we need to monitor the nests? It is because we want to know the exact number of gorillas. In the nest we can sometimes see blood, and this can mean that there has been a birth in a family. This is the importance of checking the nests.

We have just located 16 nests, and yesterday they counted 17. That means this is a big family. And in some nests they observed baby feces, so there are also babies in this group. Monitoring gives us the accurate number and size of a family. So with these 17 nests, there must be about 20 individuals."

Lambert Mongane (Chief Guide)

"He charges you like this: wah wah wah. And when he comes suddenly, be still. This is the technique, the method that our pioneer Adrien Deschryver used here in Kahuzi-Biega, so it is the same system that we also use for habituation.

And from time to time, when the male is eating, you will also eat as he eats. He eats, he watches you, take a vine, you start to eat the leaf, as he does too. This is all to show the male that we are his friends. We have just come to accompany him in his biotope. But we are not here to hurt him.

And with time, the male’s stress level will change, he reduces the intensity of his charges. If before, he charged at a 25 meter distance, he will only charge you at 20 meters, and then 15 meters, and 10 meters, and then you are friends with him."

Narration

Gathering scientific data and protecting the wildlife in this remote area is not easy. But there are other responsibilities, much more dangerous and challenging, that are part of the eco-guards' everyday life.

Bulangalire Munganga Gédéon (Eco-guard)

"It is above all, the forest that we are protecting, and this forest is threatened. As the forest is packed with rare species, and also with minerals like gold, we find ourselves in front of armed groups, rebels who are mainly looking for game, ivory. In particular, these militias are armed, it is for this reason that you find the eco-guards are also armed to be able to face these threats and militias."

Narration

These threats necessitate specialized training so that the eco-guards can protect each other and the park.

Bulangalire Munganga Gédéon (Eco-guard)

"I think the world is aware of all of this. All the wars since ‘94, the park has suffered threats, species have migrated and been killed, right up until today. Does the world not know what happened? Are the regional authorities uninformed? Does the state not know? I think my family is also aware of this whole situation, and they think that I, too, am at risk of death. And as I almost died my family was not happy, they cried, but I still continue to campaign even if my family does not agree with me, but I am fighting for the noble cause, so that Kahuzi-Biega finds its peace, so that today the Grauer’s gorillas feel at ease."

Kwitonda Ndimwibazi Deo (Eco-guard)

"When we returned (after witnessing FARDC troops poaching), we went to wait for them (at their patrol post). When they came back and saw us, they directly raised their weapons, but we thought that as they are our military there would be no problem. Directly we began to align to arrest them, but then each eco-guard was between two FARDC soldiers. They said they were going to arrest us and then, when they saw me coming, one of them stepped ahead of the others and he pointed his weapon at me. I thought it was a joke, only ten meters away, but he shot at me and when I looked the bullet was already in my arm. My weapon fell to the ground and I shouted. My colleagues fired, trying to apprehend him but he fled. Later he was arrested in his village. The State had arrested him, yet when I was released from the hospital, I saw him – he already had been set free. I have been wounded, my blood spilled, and up until today I have never received any compensation. This is how I was wounded, my chief."

Kika Kalebi Aime (Mother, Widow of Eco-guard)

"My husband died on August 1st 2019.

I could not see my husband’s body. They hid his body from me because it was in such bad condition. He was cut-up, they told me that if I saw him, I would get sick. I never saw him again.

When my husband died, I was one month pregnant with his child, and also we had an 8 month old baby."

Bulangalire Munganga Gédéon (Eco-guard)

"We can reflect: If you take your family into account, you won’t really be congratulated because you will find a woman whom you abandoned for more than 4 months, 5 months. Is this woman genuinely happy? The fact is that she never sees you at home. Are your children happy? They’re not with their dad, when he goes to fight. Does the family really have the chance to reunite with a returning father and husband? And often they might tell you to quit. When you have difficulties, you are not up to supporting the family, when you go months without being able to have a few pennies to pay, when they have not eaten. They may ask you to go elsewhere, to be a merchant, to make money. But since you still want to be someone who protects nature … You see that you will have ideas that are really contradictory."

Narration

The park consists of low- and high-altitude forest blocks. The corridor connecting these two blocks was unapproachable for decades, due to insecurity.

DeDieu Bya’ombe (Site director)

"Here we are precisely in the ecological corridor of the Kahuzi-Biega National Park. A place long occupied by farmers, and also by armed groups. Now it is liberated.

The ecological corridor is of great importance, since it is the corridor that connects the high altitudes to the low altitudes of the park. It is the transition corridor, for migration of species between high and low altitude.

It was not only the presence of farmers and the armed groups, but there was also this question of understanding or of a peaceful cohabitation, which we had to analyze. Being also a sociologist, I said to myself, first we must contact the community, and try to show them the importance of the park, and why we want this park to be patrolled thoroughly, in its entirety.

There were negotiations previous to my work here, there were high-level workshops, but they did not lead to a solution. So we had to combine these. Pressure with weapons, and negotiation or dialogue. And so I started with the pressure, and then we went into dialogue. And today we are in one tent, we are working very well with all our friends."

Narration

One particularity of Kahuzi-Biega National Park is the abrupt demarcation where the park’s forests and public and private deforested lands meet. This park is not surrounded by a buffer-zone.

Safari Cibikizi Jules (Eco-guard)

"We are already at the limit of the park, the tea plantation is outside of the park."

Narration

The increasing population living around the park struggles to find resources to survive, especially the traditionally hunter-gatherer Batwa pygmy communities. Before the establishment of the park, Batwa ancestors once lived in the forests that now comprise the park. Some Batwa say they, too, want to live in the park. However, at the establishment of the park in 1970 only around 200 Batwa people lived in the park, while at present over 6,000 Batwa people live on land directly bordering the park. Only some are actually descendants of Batwa who once lived in the park. Who should have access to the land and resources inside the park? Some international organizations encourage the Batwa communities to have a sense of entitlement to these resources. Also, local militia groups manipulate Batwa communities to take up arms and enter the park to engage in illegal artisanal mining, to make charcoal from trees, and to poach animals from the park. Reductionist narratives and manipulations promote a vision of the Batwa pygmy communities as victims, and the park authorities and eco-guards as villains. The narrative is not that simple. When the park was established in 1970, land was given by the State to certain Batwa communities, only to be deforested and subsequently sold off.

In a serious 2018 incident, members of a Batwa community illegally entered the park and stole its trees, deforesting about 400 hectares (4 km2) of forest.

Hernest Baziheraho Bavuriki (Eco-guard)

"When you passed here, the trees gave shade to this space. They were really big trees. Then the local population came and cut these trees to make charcoal, and for timber. They took the trees to burn or sell, and used some timber for construction."

Narration

For both educational and conflict resolution purposes, ICCN with the help of a local NGO, Primate Expertise, worked with the same Batwa community that destroyed this forest, to plant characteristic native tree species in the deforested block.

Nsimire M’zakaria (Muyange Batwa Village Chief’s Wife)

"The reason we came to plant these trees is that we don’t want problems anymore. We need to plant trees to replace those that we cut. Because we no longer want to destroy the environment. In this zone we cut the trees because the pygmies have already suffered a lot. So we entered the forest and cut the trees so that the park knows how to treat us. From the trees we cut down, we made charcoal and sold it on the market. Some made timber, others made charcoal. We used some of the charcoal and the timber for ourselves, but we sold some to pay for the school fees."

Chinzungu Tavuna (Batwa Pygmy Community Chief, Eco-guard)

"I am the first conservationist; the pygmies are the first conservationists for the protection of the environment. I am a state agent, but we are the first guardians of the environment. Now we try to work together with the State. You know that this is the land of our ancestors, we must protect it as such, everything that comes from this land helps us as a community. The problems, if we have had problems, were because of the lack of land. It is because when the State took our land we had no means to live, lack of shelter, food became a difficulty, schooling was a difficulty until the State took over. But we continue our struggle together with the State so that the pygmy community can have a land, and have their rights without problems, without tension and destruction."

Bulangalire Munganga Gédéon (Eco-guard)

"The Park has been threatened by indigenous Pygmy peoples. At Tshibati, there was a group of pygmies who left their villages and returned to the park to cut and char the trees. So they deforested the area. We tried to campaign to put an end to these acts. I was head of the patrol post in Tshibati. One Sunday at 5 a.m. these rebels, the (Raiya) Mutomboki (Mai-Mai militia), united with the pygmies, they came to the patrol post to attack us. We tried to defend, but I was hit by three bullets. They outnumbered us. We could not overcome them and they managed to kidnap one of our team and bring him to the forest where he suffered for a month and they even demanded money to free him. I was in the general hospital for over a month. There, they did their best with the medical technology. I’m still alive."

Narration

ICCN tries to reduce the conflict in many ways, such as by distributing staple food supplies, beans, rice, and salt, and offering many other types of nutritional, medical, and educational support with the help of local and international organizations.

Narration

ICCN also provides jobs in the park as eco-guards for members of the pygmy communities, some of whom are extremely skilled in the forest.

Bakongo Lushombo Antoine (Eco-guard)

"I was a poacher; I was trapping animals. That activity made it possible for me to get this work.

Yes, there are things that can be bad for me, because in this job, if I meet someone who is destroying the park, I have to stop them."

Narration

"Constant exposure to danger can have psychological consequences. 2 years ago, a pilot project was started in the Kahuzi-Biega National Park, the first of its kind in the country. The project, initiated by the Spanish NGO, COOPERA, offers therapy to eco-guards who have been unable to cope with the trauma endured while protecting the park."

Safari Cibikizi Jules (Eco-guard)

"It was something that relieved me, something that helped me. Because I always had sleep loss. There was a lot of stuff going on in my head, and maybe that’s why I couldn’t sleep. But the counseling, really it was something that relieved us, especially me. It helped me."

Narration

But maybe, for some, the help comes too late for the trauma they suffered.

Fikiri Lukisa Franck (Eco-guard, Armory Responsible)

"It is a service that was created, and until now, me personally, I have not yet understood what its purpose was, I just got the information from two colleagues who were there and who underwent the treatment, but I did not see any change."

Fikiri Lukisa Franck (Eco-guard, Armory Responsible)

"I became an eco-guard because of the life I led in FARDC (Armed Forces of DRC). It was a difficult life and I thought that maybe here, as there are partners who help in many ways, I thought I could have a better life here. And that my life would be happy. My family also thought it was worth the effort for me to become an eco-guard."

Narration

One solution to change the eco-guards’ perception of the trauma they experience will be a resilience building program researched and planned by the NGO COOPERA. The program, called Strong Balanced Rangers, is adapted from the Master Resilience Training created for and widely used by the U.S. Military. The goal is to teach resiliency-building skills for the prevention of disorders, such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress, which can occur due to exposure to violent and highly traumatic situations.

Narration

Consistently backgrounding the difficulties and challenges of their work, are the financial struggles eco-guards experience due to low salaries. In 2008, things took a turn for the better when the German Development Bank, KfW, began funding the efforts to protect the Kahuzi-Biega National Park. KfW significantly contributes to the wage payments received by the eco-guards. But in 2018, international news media characterized the eco-guards’ work as ‘militarized conservation’. Concerned people in Europe, who may not have understood the context in the region, demanded that the funding stop. The eco-guards continued to work and face daily risk, without being paid for 10 months from March 2020 and again for 5 months from February 2021.

Dydass Bahati Bishishe (Anti-poaching Operations & Human Rights Inspector)

"Far from me the idea of minimizing the work, because we did a lot of work with the money that the German KfW cooperation already sent to Kahuzi-Biega for many years. But if there was chaos, it was because of this. At some point, the eco-guards had uncertainties, they did not know if they would be paid or not. This is how the chaos started, but the reason was money that the partners had not sent on time, and there were a lot of months, about 10 months unpaid, that’s what caused chaos among the guards.

First of all, the work that we do is work that is paramilitary, in paramilitary work there is no union whatsoever."

Mathieu NfuneBachiga Yalire (Eco-guard)

"We always receive our salaries late, and in addition we have issues with the equipment such as jackets and boots."

Bijirikwabo Njirani Benjamin (Eco-guard)

"I have a wife at home and she’s cultivating, that is what helps me. My wife has a field of vegetables, cabbages and beans and she has a small business, with which she ensures the survival of the family until I am paid."

Narration

Why would anyone choose to be an eco-guard? This is a timely question, as enrollment of younger guards in Kahuzi-Biega National Park has drastically decreased. It would be easy to assume that in this region, any job will do. But there must be something else to it.

Bulangalire Munganga Gédéon (Eco-guard)

"We see a lot of natural disaster, landslides, we are seeing today Lake Tanganyika flooding. The natural phenomena that occur. If we continue to cut the trees, how will it be?

The eco-guards do things valuable for the whole word.

I would say it is a vocation profession. Because it’s a stressful job. You leave the house with no idea of holding a weapon and with no idea of the behavior of a soldier. You are trained and after the training you are given the weapon. They put in your mind that your mission is to fight, to combat until the supreme sacrifice, for the dignity of the forest. You are on a 20-day, 15-day patrol and you walk many kilometers every day. You arrive somewhere where you are going to camp around 8 or 7 p.m., you camp without even looking where you are going to spend the night, and you will start to settle down, to prepare what you are going to eat, and what you are eating, it is only what you yourself have carried. You see it’s hard, even your gun is heavy. But if you don’t have the vocation, you won’t get anywhere. If you don’t have the respect, the morale, you won’t get anywhere. You spend a lot of time without getting paid. Are you going to endure 10 months, 5 months? It’s risky, and you are in danger, but with that spirit of campaigning for the park, you accept that you may be killed and take risks.

If I don’t preserve this forest, I don’t see how the world of tomorrow will be, what the DR Congo will be."